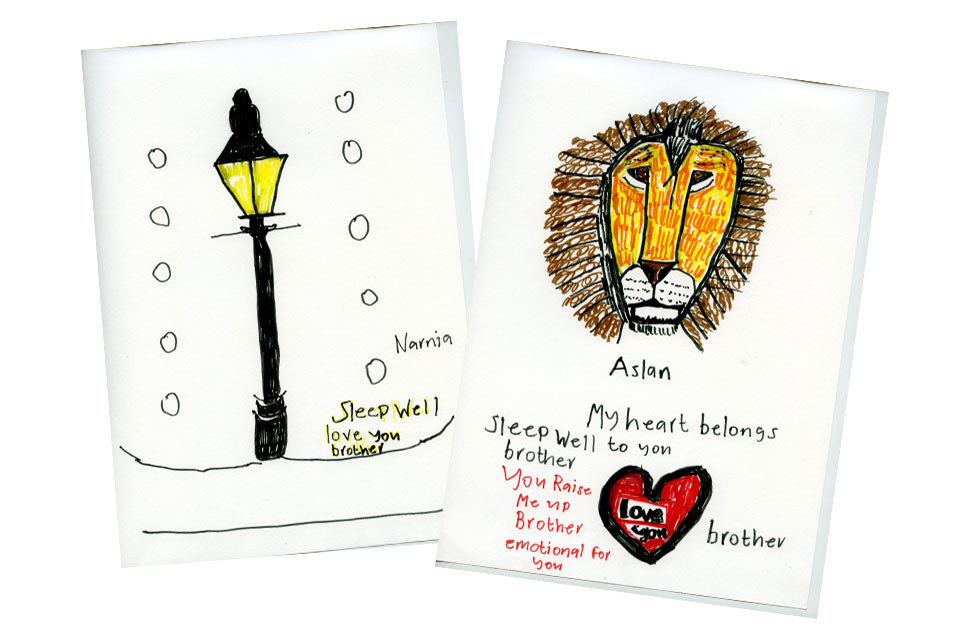

Meader’s view: Winter 2023

The latest from Community Living cartoonist Robin Meader.

The latest from Community Living cartoonist Robin Meader.

Covid persists, ordinary life is glorious and many are calling for a long-term fix..just a few recent issues that have caught our eye at Community Living.

For the latest phase of the UK-wide Coronavirus and People with Learning Disabilities Study, launched in late 2020, researchers have been recruiting minority ethnic people with a learning disability to share experiences.

Many support services are still not back to pre-pandemic levels, and there are fresh concerns about provision.

The Guardian has been among those reporting how providers commissioned by councils to support people with complex needs are handing contracts back because they are no longer financially viable.

The short-term relief in the autumn statement, including plans to raise social care spending by £2.8 billion, was welcome. However, charities such as the Carers Trust have said a long-term fix is needed.

l There was more positivity in research published by the NHS Confederation and the Centre for Mental Health. It outlined a vision to improve services for people with a learning disability or autism.

Calling for early intervention, co-production and a stronger workforce, the centre posted on Facebook: “In 10 years’ time, our vision is that these services will look different…

“Every element of this vision is already a reality somewhere in England. But to make it a reality across the country, we need investment and a willingness to make change happen.”

Providers commissioned to support people with complex needs are handing contracts back as they are no longer financially viable.

Anything is possible with the right support.

This was the motto of a team that climbed Mount Snowdon to raise funds to buy sensory and sports equipment.

The new equipment is for services run by support provider Active Prospects.

Matt Leadbeater receives support from the charity, which works with people across the south east.

Joining him on the ascent was Helen Guest, co-production programmes manager at Active Prospects Leadbeater said: “The part I liked best was seeing Wales up in the mountain and the views were stunning.”

Training for the 10 mile, six-and-a-half hour mountain trek at the end of last year included walks up Box Hill in Surrey, cycling and high-intensity interval training.

The team of nine walkers included both staff and people receiving support.

The £4,000 raised will fund equipment such as starry night ceiling panels and light boxes for sensory rooms as well as sports equipment such as adapted tricycles.

Peak progress: Matt Leadbeater and Helen Guest at Mount Snowden

Photo: Active Prospects

A campaign by Ambitious about Autism aims to stop schools giving up on autistic pupils.

The charity’s Written Off? campaign demands the government protects special educational needs and disabilities (SEND) funding and families’ legal rights to get support for their children.

Research among 2,000 families and young people showed two-thirds (65%) of families were unhappy with their child’s mainstream education. More than one in three (36%) autistic pupils reported being out of school against their wishes.

The government is reviewing the SEND system. Families fear its green paper proposals, including limiting the ability to choose a school, will make it harder for children to get support in education.

The LDA Collaborative – LDA stands for learning disability or autism – is led by Leicestershire Partnership NHS Trust and involves Leicester, Leicestershire and Rutland Integrated Care Board.

Good social and legal work meant an elderly woman was able to remain at home, cared for by her son, despite them both having hoarding disorders and support needs, reports Belinda Schwehr.

A recent court of protection case has highlighted how positive social work combined with good legal support enabled a 92-year-old woman to be cared for at home in line with her wishes.

The case (Re: AC and GC) involved Her Honour Judge Clayton supporting a trial period of care at home instead of residential care for the woman, who had Alzheimer’s disease, alcohol-related brain damage and a compulsive hoarding disorder.

AC had been living at home in Coventry with her son, GC, who was also her carer and sole attorney for property, affairs, health and welfare.

GC had Asperger’s syndrome, anxiety, obsessive compulsive disorder, a hoarding disorder and depressive episodes.

Back in December 2021, the court had suspended the son’s lasting power of attorney for health and welfare but he retained attorney status for his mother’s property and affairs.

An order had stipulated that GC left the home while it was being made safe and clean.

GC had litigation capacity. However, he was assessed as lacking capacity to make decisions about his own and AC’s financial affairs and about his own and his mother’s belongings.

An order had stipulated that the son left the home while it was being made safe and clean

She was discharged from hospital to a care home through a court order made in her best interests at Coventry City Council’s behest. The court made a declaration that the woman lacked capacity to make decisions on her care, residence and litigation.

The official solicitor – who acts for those who lack capacity and cannot act for themselves – represented AC’s interests in a challenge to a Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards (DoLS) authorisation under the Mental Capacity Act 2005. DoLSs protect people who cannot consent to care arrangements if these deprive them of their liberty.

Care at home trialled

AC consistently expressed her wish to be cared for at home. She had lived in her house for 40 years and wished to die there. She missed her son and her cat Jasper.

The local authority did not support a trial period of care at home because of the high risk of care breaking down and the likely distress that would follow.

The judge disagreed: “A trial of care at home is not without risk but, on the evidence before me, it is a manageable risk and one which should be taken to try to afford AC the opportunity of returning to her home, in improved circumstances, and with the hope and expectation that it will continue to improve in the coming weeks and months…

“I could not be satisfied that a final placement at the care home would be an appropriate and justifiable interference with AC’s article 8 rights [under the Human Rights Act].”

Those involved in this case looked at Westminster City Council v Sykes, which had considered the value of being cared for at home at the end of life to a person with a progressive condition.

The judge in Sykes found: “Several last months of freedom in one’s own home at the end of one’s life is worth having for many people with serious progressive illnesses, even if it comes at a cost of some distress.

“If a trial is not attempted now, the reality is that she will never again have the opportunity to live in her own home.”

Given AC’s and GC’s mutual emotional dependency, the judge concluded that a 10-week trial period for care at home was in AC’s best interests. AC would share the cost of retaining the care home room with the council. A self-funder, AC had £240,000, which would cover the care costs in either setting.

The new deputy who had been appointed would be empowered to remove items from the property whether they belonged to AC or GC. They would employ cleaners, which would improve the relationship with the care agency.

Conditions

Great care had been taken over the conditions needed for AC to take up this trial; the court found it significant that GC agreed to them all.

Conditions included that GC was trained on moving and handling, received ongoing therapy and committed to giving full access to care workers.

GC also agreed to vaping rather than smoking indoors, checking the kitchen weekly for out-of-date food, not drinking alcohol when expected to be half of a care team and cleaning the house weekly.

He also had to give notice of any respite he would take, agree to unannounced monitoring visits and not leave his mother alone for more than two hours.

Notably, the judge praised “the very fine work which has been carried out in this case by all of the professionals… [as well as] the high quality of the work undertaken by the social worker”.

The social worker had produced 10 witness statements, describing the condition of AC’s property and stating that some progress had been made with the lounge, hallway, kitchen bathroom and AC’s bedroom.

The fire service confirmed that the risks had dramatically reduced from when they were first involved. One care agency was happy for GC to be a second carer, provided that he received training, and said the hoarding would not be an issue.

The judge praised ‘the very fine work which has been carried out by all of the professional and the high quality of the work by the social worker’

Legal aid

It may seem unusual that AC got legal aid despite having access to £240,000. That is because any challenge to a DoLS authorisation under section 21A of the Mental Capacity Act attracts non-means-tested financial support as such cases are associated with human rights.

And, while the judge thought well of the efforts of the local authority in this case, the question remains whether a council would try quite so hard for someone it had responsibility for placing or if they were less wealthy.

This judgment is also notable for outlining the consequences of hoarding – information that will be useful in future cases.

This case resulted in a humane, civilised outcome for both the person support and the family carer who also had support needs.

As such, it will be of interest to anyone looking to support family carers and uphold an individual’s desire to be cared for at home.

Good social and legal work meant an elderly woman was able to remain at home, cared for by her son, despite them both having hoarding disorders and support needs, reports Belinda Schwehr.

The woman’s son had given up his job to support her when her husband – his father – had died. However, his own difficulties eventually undermined his ability to continue caring for his mother alone.

The court showed sensitivity to the issues in this case. The judge visited AC, learning for herself the importance of her relationship with her son as well as her deep desire to remain at home.

It was significant that the son found the therapy worthwhile – the attention and help of a skilled therapist was possibly the only input he had received for a long time – and, because of this, could deal with the conditions required to get his mother home.

It is worth remembering that counselling can be bought under the Care Act if the NHS will not pay for it.

AC and GC (capacity: hoarding: best interests) [2022] EWCOP 39. https://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWCOP/2022/39.html

Westminster City Council v Sykes [2014] EWCOP B9. http://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWCOP/2014/B9.html

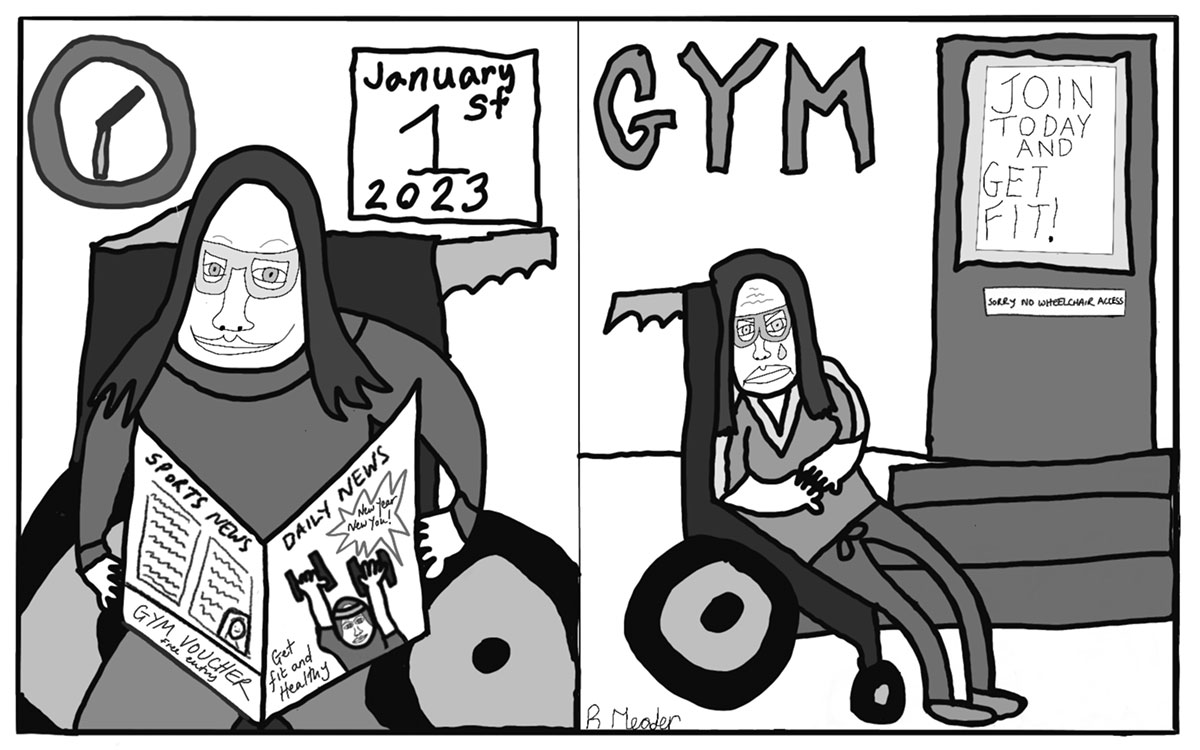

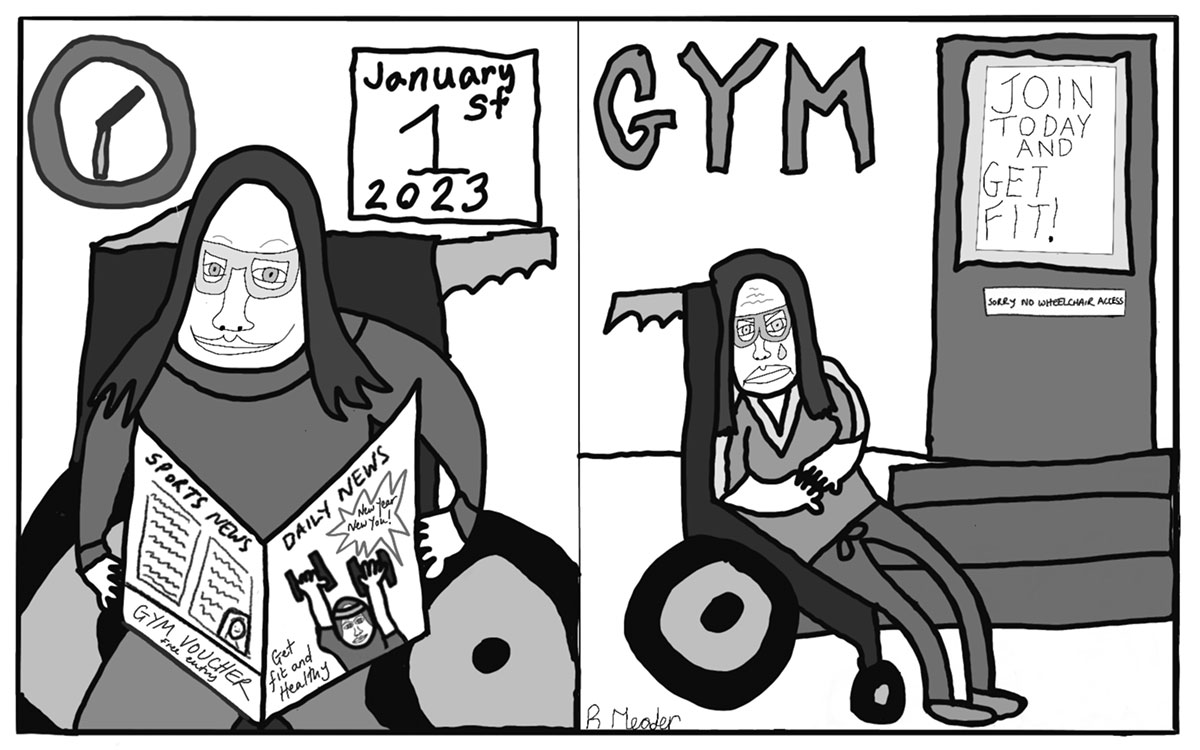

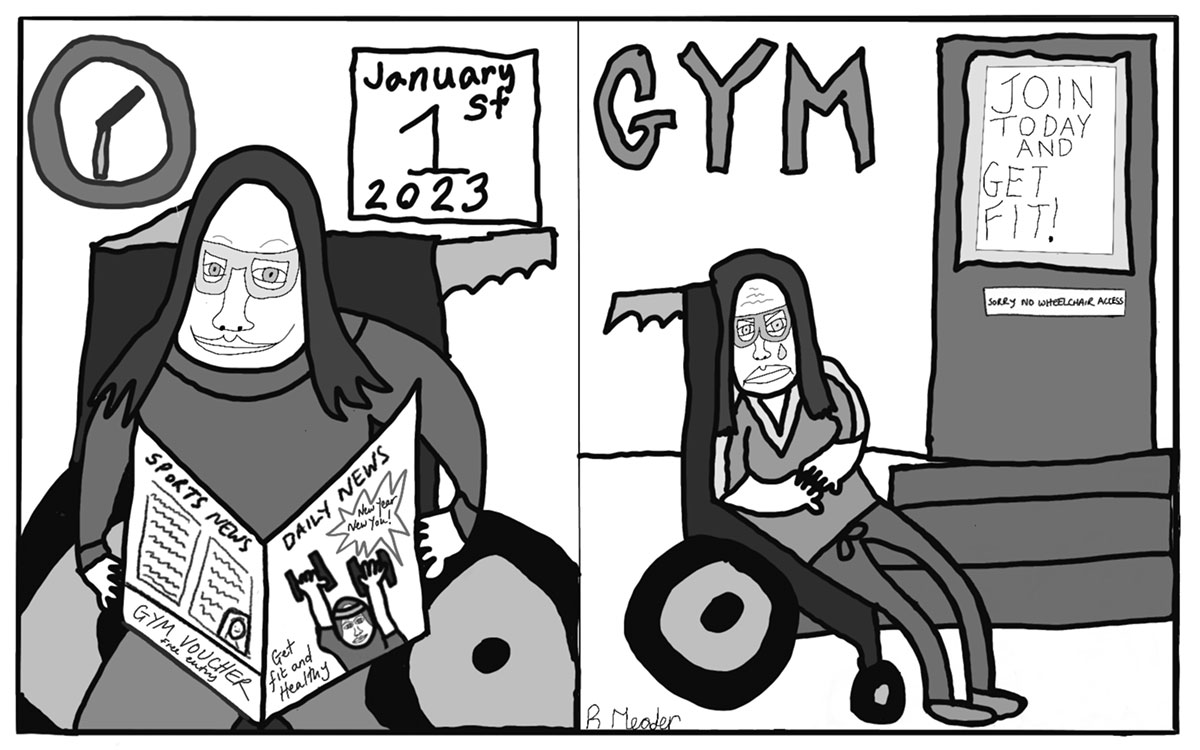

Everyone deserves the opportunity to take part in physical activity, and the new year is a great time to reflect and hit that reset button, writes Jade Mottley.

As the year starts, thoughts turn to healthy resolutions. Fitness trainer Jade Mottley advises on making physical activity open to all, and Olympian cyclist Kiera Byland aims to inspire athletes.

Trainer Jade Mottley believes fitness should be more accessible – Photo: Jade Mottley

Everyone deserves the opportunity to take part in physical activity, and the new year is a great time to reflect and hit that reset button, writes Jade Mottley.

My advice is to start your journey today, and know that small steps – such as going for a quick walk or eating a piece of fruit – add up.

Many of those I have worked with since launching social enterprise Performance for All in 2015 face barriers simply because fitness professionals lack experience in training people with disabilities.

My approach is to ask someone what they can do, not what they cannot.

Working with a person with additional needs brings additional risks. Some coaches do not want or know how to deal with these. For trainers, it comes down to confidence; you adapt sessions and think outside the box.

Both trainer and client have to want to have fun, be safe and be willing to try.

Adapted sessions

Some people need visual cues added to a verbal instruction, such as counting on the fingers, or sessions may need adapting for wheelchair users. I once turned a wheelchair into a leg extension machine using a resistance band and a foam cylinder.

I ran “signed sweat” sessions in lockdown, securing funding for a sign language communicator.

I then did a master’s degree in Manchester. Standout moments included working at Manchester United FC’s deaf team, and with the Special Olympics as a training lead for its schools programme.

I worked as a personal trainer and nutrition coach with Special Olympian Kiera Byland.

We raised awareness of disability sport in the north west, talking in schools about activity and diet. Gaining National Lottery funding for this project eventually led me to set up Performance For All.

While the most common aim I hear is that people want to be healthier, reasons range from desires to be more confident and sociable to losing weight. See someone grow in confidence far outweighs what the scales show.

To know getting fitter has helped someone in other areas – such as by becoming more confident at work or going out for walks with family – it makes the 7am training sessions well worth it.

As the year starts, thoughts turn to healthy resolutions. Fitness trainer Jade Mottley advises on making physical activity open to all, and Olympian cyclist Kiera Byland aims to inspire athletes.

My goals for 2023 are to inspire other Special Olympics athletes to have health and fitness goals. This includes having good mental health through the Special Olympics Strong Minds programme, which teaches mental exercises and provides resources to boost relaxation and stress management skills.

I am also passionate about the Special Olympics’ Fit 5 programme to boost healthy lifestyles and physical activity.

For people with learning disabilities to get into sport and fitness, we need clubs and coaches to give us a chance.

While you might be nervous, please be inclusive and give it go. You can learn so much from people like me – we have a lot to offer coaches through our own experiences and stories.

As a cycling and swimming coach, I can give back and inspire others by being a positive role model, whether this is helping them just to keep fit and healthy or to compete too if they want.

If someone is finding it hard to reach their sport or fitness goals, I would say: don’t set these too high or too low. Setbacks happen, so take a deep breath and take one day at a time.

Kiera Byland is a Special Olympics six times gold medallist, a swimming and cycling coach and a member of the Special Olympics global athlete leadership council

Kiera Byland: people with learning disabilities have a lot to offer coaches through their stories and experiences – Photo: bolton College

On supported internships, young adults develop skills and maintain jobs with the help of expert job coaches. The number of these positions is set to double, reports Julie Pointer.

Dave Hanford (with job coach Stu Neville): “There’s lots I can do now that I might not have attempted before”- Photo: NDTi

New year, new career is a common theme for many of us.

But for people with autism or a learning disability, getting a first job is hard enough, let alone getting a new one.

Only 5.1% of UK adults with a learning disability gain permanent, paid employment, compared to 80% of their non-disabled peers.

Employment support for people with additional needs has been historically underfunded, leaving a lot of very capable and motivated people overlooked.

This status quo is being challenged by a partnership to boost equal employment opportunities – Internships Work – launched in September 2022.

This is a collaboration between social change charity the National Development Team for Inclusion (NDTi), the British Association of Supported Employment (BASE), and DFN Project SEARCH, which runs a transition to work programme for young adults who have a learning disability or autism.

The programme, funded by the Department for Education, aims to double the number of supported internships for 16-25 year olds with additional needs in England by 2025. Around 2,250 supported internships are currently provided per year; our goal is to support businesses to create 4,500 placements each year.

What’s involved

Supported internships are work-based study programmes involving a work placement of 6-12 months, supported by an expert job coach, who helps people learn, develop and maintain their role.

NDTi will manage the internships and DFN Project Search will support employers to offer more high-quality internship models, training business champions and local SEND employment forums.

BASE will improve internship quality, working with councils, education providers and employers, enabling employers to achieve a quality mark. It is also training 760 job coaches.

Dave Hanford, 37, is a business support administrator at NDTi in Bath. He has been working with his job coach Stu Neville for five years. He has previously held an administrative role at a local company, a role that Neville also supported him in.

“Stu encourages me to have a go and has helped me increase my confidence in my own abilities,” says Hanford.

“I’ve learnt to get on with things when he’s not around and there’s lots I can do now that I might not have attempted before.”

Neville says: “I’ve supported Dave through two jobs now and seen him grow and learn with each.

“The best piece of advice I can give to anyone about to work with a job coach is to communicate. If you don’t understand something, say so and we’re there to help you.”

“I’ve learnt to get on with things when he’s not around and there’s lots I can do now that I might not have attempted before.”Internships Work’s goal for early 2023 is to gain a clear understanding of where every local authority is at with intern positions and what needs to be done.

For example, councils could improve their information on employment pathways. The programme is pulling together resources to help them with that.

The aim is for more young people to develop skills to become independent and more employers to improve how inclusive they are.

We know there is a large talent pool out there – we just need to match them to the right jobs.

Julie Pointer is programme lead for children and young people at the National Development Team for Inclusion.

Support for intimate relationships is often lacking or taboo, and training for workers is scant. Claire Bates looks at why this is the case and how materials to address this were co-produced.

People may need support when considering an intimate relationship - Photo: Seán Kelly

There are many reasons why relationship support is overlooked. There are misconceptions around sexual desire, romantic interest, abilities to form relationships and mental capacity, to name a few.

A taboo persists and it is time it was – literally – put to bed.

Article 8 of the Human Rights Act states people have the right to a private life, including the right to consensual sexual expression in private. Many people fail to achieve this, because of issues such as restrictive practices, no awareness of their rights and a lack of education for both them and support staff.

We are combating these inequalities though Supported Loving, a national network founded in 2017 and hosted by social care charity Choice Support.

Through this, people share best practice, develop guidance and champion sex-positive, active relationship and sexuality support. There are more than 1,500 members, including social care staff, self-advocates, social workers, nurses, educators and family members.

Supported Loving campaigns for changes to reduce this taboo in care, such as including sexuality support in inspections by social care regulator the Care Quality Commission.

In 2019, we started a project with workforce development body Skills for Care. This included a review of learning materials for staff on sexuality and intimate relationships.

Surprisingly few training resources for staff existed. Focus groups with 120 social care staff highlighted how many found it difficult to discuss these sensitive topics. They said it was hard to know what to say, how to say it and what you could or could not say.

Our review did not identify any resource that gave practical advice such as how to start conversations, examples of words to use and where to find more information.

In response, several Supported Loving members developed Shoo the Taboo. The aim this is to reduce taboos around sex and relationships and help care and support staff feel more confident in responding to sexual expression.

The pack includes 50 A5 cards that inform and encourage and further exploration. These can be used with individuals and groups. There are 10 cards for each of the five sections: sex-positive relationships and sex education; sexuality and relationships within the law; diverse sexuality and gender expression; online activity for sex or relationships; and supporting relationships.

Cards are based on the authors’ experience in social care as practitioners and trainers, and reflect concerns raised by staff.

Shoo the Taboo took more than a year to develop and was launched in April 2022.

Outraged responses

Professionals and people with learning disabilities gave feedback on the cards. The most memorable aspects were the latter’s reaction to questions posed on the cards – they were, rightly, outraged.

For example, one question was: “My manager says I have to keep the door open when a partner visits – is that what I should do?” Another was: “My colleagues have said the people we support don’t have any sexual feelings, so there is no need to think about it. Should I go along with them?”

Responses from people with learning disabilities included comments such as “it’s not right” and “they shouldn’t say or do that”. One support worker said: “I used to get really worried I wasn’t allowed to say this or to talk about it but I now feel much more confident.”

While it was upsetting to share how some staff perceive people’s sexuality, it was rewarding that those involved in the Supported Loving network knew this was wrong and should be challenged.

We plan to use Shoo the Taboo sales proceeds to host an event where people with learning disabilities and professionals can learn and have fun – and explore how to shoo this taboo for good.

Claire Bates is Supported Loving Leader at Choice Support

Skills are being tapped and items created for sale and display in stores, cafes and shows, reports Mike Casey.

Garvald baker Patrick Dooley

Garvald baker Patrick Dooley

I like the work, I like doing this. I like making things,” says Brian Baird.

“I always try to do my best. I sometimes kick myself for not doing things properly but I shouldn’t because it is just part of learning. I like to do things that make us think.”

Baird, a 49-year-old Garvald Edinburgh joinery workshop member, has produced eight fine beechwood chairs for the Botanic Cottage at the Royal Botanic Garden in the city (pictured).

The Botanic Garden’s Laura Gallagher is delighted with the commissioned work: “We approached Garvald because of the quality of the craftsmanship and the strong community links.

“Brian made each one himself. He is a very skilled man and has done a wonderful job.”

Garvald runs more than 20 workshops, including textiles, glass, baking and confectionery, jewellery and puppetry, from Edinburgh and the Lothians.

Established in 1969, Garvald takes its inspiration from the ideas of philosopher Rudolf Steiner and social therapy.

We believe any person will blossom if they feel valued and part of a community where they are recognised for who they are and not diminished by labels.

We have tried to create an environment where the 230 people who use our facilities can unleash their creativity through arts and crafts.

Our Orwell Arts studio, for example, has floor-to-ceiling windows that fill the space with a light and stripped wooden floors. Having a beautiful environment helps people to engage fully in their craft.

Members produce bread, cakes and biscuits for 14 outlets in Edinburgh. Art and glass works were shown at the recent Edinburgh Art Fair, and textile products were on sale at the Glow design fair.

Glow founder James Donald says: “The quality of the work really impresses me. They do a great product range and there aren’t that many weavers out there.”

Joinery workshop leader Rebecca Kemmer, who works with Baird, says: “The people are very capable and I would hate for people to think that just because somebody has a disability that they’re not truly skilled.”

Members are supported to develop confidence and resilience through meeting and building friendships alongside others with shared interests.

We also believe in making for a purpose, an end product that its creator can be proud of and sell or display to the public alongside work by other professionals and crafts people.

Some of our members have accumulated more than 10,000 hours in our workshops, the threshold when one becomes considered an expert.

“It’s incredible to see the members’ development,” said Layla Tree, one of the leaders of the textiles workshop.

“Someone I work with who has autism is amazing at remembering sequences and patterns and despite initially not wanting to touch any materials has developed into an independent weaver…. I do firmly believe that through weaving their lack of confidence and their anxieties have diminished.”

One of those weavers is Kieran Thompson, who has completed a number of commissions for Garvald.

“I enjoy weaving. It’s quiet and I can concentrate more. I feel smiley, happy and proud. I get good experience from the staff helping to show me how to do weaving. I’m so happy they show me new things.”

Mike Casey is chief executive of Garvald Edinburgh

Photo credits: Joe Tree (textile and weaving images); Garvald (Brian Baird and chairs); Andrea Thomson Photography (Patrick Dooley)

As my profoundly disabled son approaches adulthood, I realise that being able to talk candidly about family experiences will make society a little more understanding.

Elliott, my eldest son, will be 18 in the summer. His lumbering frame – all 6’4” of it – clatters around the house in deep-throated guffaws as I write this and it’s hard not to wonder: “Where did my little boy go?”

It seems like a heartbeat ago that I was in a London hospital, gazing on him as a newborn and promising him a world filled with joy, adventure and love.

But “Where did my little boy go?” is a loaded shotgun of a question. Where did he go?

That boy was never really there.

Sure, those early days came with all the sleepless nights and smelly nappies you expect when you first become a parent. But, for Elliott, they never went away.

Elliott never learnt to talk. Never learnt to dress himself. Never learnt to read. One by one, Elliott missed milestones that his friends surged past. I say friends. He never really made those either.

Each milestone missed was a step away from the life I thought lay ahead for him and for us.

Elliott was diagnosed with autism aged three. At the time, I had no real idea what that meant.

So I did what every parent does when they receive a life-changing diagnosis about their child; I read the books, joined the support groups and trawled the internet searching for something to help me understand what had happened.

The NHS specialists’ conclusions were opaque, doing little to help us understand or to plot a course forwards. We paid to see private sector specialists. Same conclusions, different price tag.

We found ourselves at the extremities of the autism spectrum. In a world that was growing to understand these disorders as ultraviolet, Elliott was living a life that was infrared.

In the end, we stopped saying he was autistic and instead said we had a son with learning disabilities – a term that didn’t come with any expectation beyond an understanding that things were hard for Elliott in a way that most people could never comprehend.

What can I tell you about Elliott?

I can tell you of his love of CBeebies.

I can tell you how hard fought each little step on his learning journey is.

I can tell you of the hours he has spent happily in the back of our car, watching the world go by.

I can tell you how things overwhelm him and flip the ordinary into chaos without warning.

I can tell you how angry I am that this is the hand he was dealt.

I can tell you how proud of him I am.

Because, whenever I have shared the story of our family – be it in tweets on TV or in podcasts – it has been with two truths in mind.

Being Elliott’s dad has been the best thing that ever happened to me.

Being Elliott’s dad has been the worst thing that ever happened to me.

That these two truths are hard to reconcile doesn’t make them any less true.

In talking honestly about what it’s like to be a parent to a child with profound learning disabilities, the good and the bad shared with equal candour, I hope to make the world a little less infrared for people like Elliott.

And, ultimately, I still hope to keep those promises I made to Elliott when he was a newborn and I guess my hopes for him now are not so different from my hopes back then.

To be happy and to be loved. To hope for those is enough.

As my profoundly disabled son approaches adulthood, I realise that being able to talk candidly about family experiences will make society a little more understanding.

It would be easy to write about how hard Elliott’s disabilities have made his life and our family life. But to do so would be to neglect the delight and happiness Elliott finds in his world.

Elliott is never happier than when he is in water.

To Elliott, a swimming pool or, especially, the sea is a world of relief that almost literally washes away his struggles.

He adores plunging in, jumping up and down and letting the water rush over his head and surge through his fingers.

Our Sunday morning swims have been moments of bliss for more than a decade and are the one time Elliott can totally relax and play freely with his siblings.

Many people thrive in supported living. However, with the shortage of social housing, we need the finance and the flexibility to secure homes from elsewhere, says Suzanne Gale.

I recently went to meet a tenant in her flat to check she was receiving the appropriate support from her provider and was delighted to be turned away.

The woman, in her 30s and living in north London, felt I did not look enough like the photograph I sent her ahead of my visit (it was an old one).

I was delighted because her decision to refuse entry reflected her right to choose who should cross the threshold into her one-bedroom, ground-floor flat. Our meeting went ahead after she called her support worker to check.

Even if you need significant support to live in your own home, with the responsibilities of having to pay bills and save up for a sofa, it comes a sense of empowerment and pride.

As a social care and health consultant, I have seen so many people thriving in supported living, like the tenant I visited.

Supported living means people have their own tenancy that is not directly linked to their care and support. This enables more control over who supports you, how you spend your money and who you live with.

It will not work for everyone – and sometimes councils see this sort of housing as a placement rather than as a home with a tenant’s rights and responsibilities – but we are being more creative about trying to make it possible.

Despite this, the latest Office of National Statistics data shows around two-thirds adults with a learning disability are still living with their parents, compared to approximately 18% of people with no known disability.

There was a big push at one time for social landlords to build and adapt homes for people needing additional support, and funding to make this happen.

The Supporting People programme, introduced 20 years ago under the Labour government, provided ringfenced funds, a framework and clear guidance to regulate the sector locally.

However, with a change of government, the programme took a back seat, and supported housing became less regulated and inappropriately funded. The ringfence around council funding for housing-related support services was removed.

The government must find a way to identify the landlords that are in it for the right reasons

There is now no specific budget for supported living services and councils do not have a statutory duty to ensure people are in appropriate accommodation; their only responsibility is to the Care Quality Commission on the care aspect.

Supported living has been criticised for becoming a playground, with organisations merging and rebranding at such a rate that tenants have virtually no chance of even knowing who their current landlord is.

And, as with all social housing, demand has outstripped supply, leaving the sector chasing its tail. Consequently, the option has been to turn to the private sector.

For private landlords and developers, offering homes to those with support needs while making a reasonable profit could be an attractive option.

Councils with vision have responded, helping landlords understand the requirements of supported living, and working with families and carers to help people move into their own home and towards something resembling equality in housing options.

But, to reach equality, supported housing needs a hand up, with the markets and economic problems working against it.

The government must acknowledge that supported housing can cost more. It must find a way to identify the landlords and developers that are in it for the right reasons – and support them accordingly.

I speak to dozens of people who invest in property who are deterred from being involved in supported housing because of difficulties in getting a mortgage, writes Lisa Brown.

Several have put forward a property for supported living, the provider gets excited with the great match for their tenant – then it falls through because the investor cannot get a mortgage.

Stricter criteria

Lending criteria are often stricter for investors looking to buy property for supported housing. In addition, only a limited number of insurance products will cover a landlord whose tenants have support needs and these tend to be more expensive.

With only a limited pool of mortgages available and buy-to-let mortgages being more expensive, landlords must pass on these costs through higher rents.

Repossession risks

Lenders need to consider the risk of non-payment and have the right to repossess the property. If a landlord does not or cannot manage the mortgage, the lender could be concerned about reputational risk if they have to repossess a home and evict tenants with disabilities.

Nonetheless, a property with a long-term tenant in situ is an attractive prospect to an investor – why would lenders need to evict the tenants?

If a landlord defaults on mortgage payments, the lender could repossess the property and sell it to another investor.

Being a landlord

Investors are expected to have experience as a landlord as lenders see supported housing as complex. However, in reality, the support or housing provider will be managing the tenancies.

If tenants need 24-hour care, again, this puts off lenders. This makes no sense. Having carers on site 24 hours a day means a property is better protected.

It may be that lenders do not realise staff do not live in the property and are concerned about them acquiring tenancy rights.

Or is it discrimination against those with the highest needs on the part of lenders wishing to protect their reputations?

What are the answers?

We need more mortgage products that allow for any type of tenant regardless of support need.

We need to hold more conversations with lenders so they make informed decisions. Showing evidence of demand and the business opportunities will drive the creation of products.

Property investors, lenders and supported living providers need to understand each other and how they fit in it. The groups speak different languages.

We need to understand each other better in order to facilitate the creation of more homes for people who have support needs.

Lisa Brown is a supported living property investor and advocate and founder of the Supported Living Property Network

How those who are responsible for their own support shape their lives and the role of adult brothers and sisters in inclusion are addressed in recent studies, reviewed by Juliet Diener.

Actively belonging

Kaley A, Donnelly JP, Donnelly L, Humphrey S, Reilly S, Macpherson H, Hall E, Power A. Researching belonging with people with learning disabilities: self-building active community lives in the context of personalisation. British Journal of Learning Disabilities. 11 June 2021.

This study explored how learning-disabled people are building lives that support them to feel they belong in the community.

The authors designed a qualitative project with input from local people (such as neighbours and shopkeepers), support bodies, local authority representatives and learning-disabled people.

Presented in an accessible version, the study looked at how “people with learning disabilities and their allies are ‘self-building’ their daily lives when responsibility for daytime social care and support is handed to them”.

Interviews, focus groups, observing activities and photovoice (photography to guide interviews) were used to examine how belonging was created and supported.

While, with personal budgets, people are increasingly shaping day-to-day life, social care cuts mean personalised care lacks funding and consistency in relationships. This impacts the creation of meaningful belonging.

Participants were clearly able to identify spaces that encouraged or discouraged belonging. Examples included a local shop where staff were friendly and feeling time pressure on a bus from drivers and passengers.

This project explored belonging as an interactive state where a person and their allies are active, not passive, in creating “meaningful engagement and reciprocal relationships within local neighbourhoods or networks between people with and without disabilities”.

A key finding was the importance of feeling welcome in everyday spaces at all times, making friends, being part of regular social networks, and being informed of what was happening in their community and support available.

This research gives insights into making day-to-day living accessible and community focused.

Sisters and brothers

Boland G, Guerin S. Connecting locally: the role of adult siblings in supporting the social inclusion in neighbourhoods of adults with intellectual disability. British Journal of Learning Disabilities. 4 July 2021.

This study explored the role of adult siblings in connecting their learning disabled sister or brother to life in the community. Little research has examined this.

The authors asked two questions. First, what role – if any – do non-disabled adult siblings play in supporting their brother or sister to engage in their locality? Second, what are the experiences of: the siblings offering support for local engagement; and people with intellectual disabilities of being supported by their brother or sister?

The use of a multiple dyad (two individuals) case study methodology and semistructured interviews enabled researchers to gather a wealth of data.

Siblings shared their joys and difficulties of supporting local engagement, with the authors noting that “levels of involvement with their brother/sister with intellectual disability varied considerably, influenced in part by emotional bonds”.

Participants were clearly able to identify spaces that encouraged or discouraged belonging.

For the adult with the learning disability, sibling engagement offered “emotional and practical support in their lives”. Many of the non-disabled sisters and brothers supported their relative through their own networks.

While experiences were diverse, siblings’ involvement is relatively new to service providers; they are often left on the margins of the systems supporting their relative.

Final conclusions noted the value of shared activities that are enjoyed equally by both siblings and offered “the potential to lead to developing acquaintances outside family and service provider circles”.

The history of contraception over the years shows that women’s sexual health, reproductive rights and protection from abuse have never been priorities.

It’s great that people with learning disabilities now officially have rights to a family and relationships.

Historically, this has been a fraught issue.

The policy motivator until the mid-20th century was fear that the “feeble minded” would have more children than others, leading to “a terrible danger to the race”, as Winston Churchill wrote to prime minister HH Asquith in 1910.

At the time, there were two ways to prevent people from having children – keeping the sexes apart or sterilisation.

In the UK, segregation was adopted; involuntary sterilisation was never formally sanctioned. In institutions, men and women met only when supervised by staff.

Many people remained outside these institutions. What of them?

I was shocked to find government forms from the 1930s that asked officials checking up on those living with families: “Is it considered that the control available would suffice to prevent the defective from procreating children?” If the answer was no, placing them in an institution would be considered.

The pill was a game changer. Institution staff made sure women took it (many patients were probably unaware what it was for) and could feel permissive about heterosexual relationships between patients.

However, people in the community could not be relied upon to take the pill. The government refused to officially countenance involuntary sterilisation but there is no doubt it was widely practised.

I once interviewed a couple who in 1970 had asked their GP if their daughter, then 20, could be sterilised. She never forgave them for taking away her ability to have kids.

But, they asked, what were they to do? She liked sex, and they did not want the responsibility for helping her bring up children.

Related to this is the lack of support for well-woman issues – to say nothing of poor diagnosis and treatment for female-specific conditions and cancers

In Know Me As I Am, a 1990 anthology by people with learning disabilities, one contributor said: “People like us don’t have babies. No one at the centre does apart from staff. Some people have their stomachs taken out.”

Today, women with learning disabilities are nearly four times as likely to use long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) as other women – a rate of 46% versus 12%, according to Public Health England.

What little research has been done indicates these women are prescribed LARC (or other non-barrier methods such as the pill) at a younger age than others, stay on them for longer and, astonishingly, remain on them even if not sexually active. Reasons offered include “to manage menstruation” or in case they are taken advantage of. We do not know how many women are taking contraception for these reasons – we should.

What’s the message here?

At no time has the sexual health of women with learning disabilities been the primary concern.

Many would prefer it if women with learning disabilities do not become mothers. But the issue is bigger than a neglect of women’s desire to become parents.

It extends to a failure to protect from abuse, from sexually transmitted disease and from unwanted (by the woman herself) pregnancies. It’s a failure to provide support for women to have whatever safe and physically and emotionally rewarding sexual relationships they choose. It’s a failure to help draw boundaries to protect women from exploitation.

Related to this is the lack of support for well-woman issues – puberty, menstruation and menopause – to say nothing of poor diagnosis and treatment for gynaecological conditions and female-specific cancers.

The manager of a residential home once told me she was shocked that residents were not allowed out of their rooms between 10pm and 7am. Nowhere was this written down – it’s just what happened until she changed it.

When I asked about overnight visitors, she said yes – then added that families had a lot of interest and staff would have to check with them.

History tells us that looking at the policy is not enough. We need to look beyond what people say they do and at what actually happens.

Photo: Jacqui Brown/Flickr

The lives and the experiences of black British people are under‐represented in the history of learning disabilities. Paul Christian takes a trip down the archives to help put this right.

Paul Christian – photo: The Other Richard

As a black person with a learning disability, I’ve often wondered where I might fit as an activist. The lives and experiences of black British people like me are under‐represented in the UK history of learning disabilities. I am proud of my Jamaican heritage.

I have lived with the label of learning difficulty since I was a child, attending a special school before going on to train as an actor at the Royal Central School of Speech and Drama, and perform with London-based learning disability theatre company Access All Areas.

Following the brutal killing of George Floyd by police officer Derek Chauvin in the US, Generate Voices was formed. This is a group of people with learning disabilities, which is facilitated by London‐based community support and employment organisation Generate. The group came together to understand and take action against racism.

When I interviewed the group as part of my activism work, everyone highlighted a lack of accessible information about black history as a substantial problem.

At the same time, my own writing in support of Black Lives Matter for the Surviving Through Story Covid project (supported by the Open University) brought home how much information essential to understanding race and racism remains inaccessible.

I met Sue Ledger in 2014 through Access All Areas and we started to research and write together. I am working with her on the easy-read project and she worked with me on this article.

Ledger is a visiting research fellow at the Open University and we both live in Hackney, an area of London with a diverse population.

When George Floyd was killed by police in the US, we both supported the Black Lives Matter protests that followed.

Education

Records about the Black Education Movement (1965-1988) include photographs of schools for black children organised by black community members who were worried about the quality of education their children were receiving and their lack of access to black history and role models.

Activism

In 1981, 13 young black people died in a suspected arson attack on a birthday party at a house in New Cross, London. There are records about this fire and the ensuing Black People’s Day of Action protest.

Arts

The archive holds records about the Caribbean Artists Movement (1966-1972) set up to prevent the marginalisation of artists and writers. It gave creatives opportunities to meet and share their work.

Publishing

Material held in the archive includes a collection about a series of international book fairs of radical black and third world books between 1982 and 1995.

A visit to the archive

The George Padmore Institute, named after influential pan-Africanist and writer George Padmore, was set up in 1991 by a man called John La Rose. La Rose was an activist, poet and publisher.

His dream was to encourage understanding of the history and experiences of black communities of Caribbean, African and Asian heritage in Britain and Europe.

The collection contains materials about some of the most important and successful movements, events and campaigns organised by black communities in Britain from the 1960s to 2000s. The institute has at least 13,000 items on its database.

The organisation, which is a charity, helps organise black history talks and workshops, taking items to and holding workshops in schools and community settings, as well as publishing books and other materials.

Ledger and I first visited the George Padmore Institute in January 2022. We started off by visiting the New Beacon Bookshop, Britain’s first black publisher and bookshop. Thumbs up to it. It was a great place.

After we had looked round the bookshop, we went upstairs to the institute to meet archivist Sarah Garrod. As you climb the stairs, you can see calendars from the 1980s published by New Beacon Books.

At the time, many families were saying images of black children in the press tended to be negative and associated with bad behaviour. In response to this, New Beacon published calendars showing black children and young people doing ordinary childhood things – playing, reading, having fun – no different from any other child or young person.

Seeing history: Paul Christian is working on easy-read materials for the archive – photo: Sue Ledger

New Beacon Books was set up by John La Rose in 1966. At that time, it was the only independent black publisher and bookseller in the UK.

In the 1960s and 1970s, it was hard to find publications with positive images and stories about black children and families and black history in general.

The bookshop made these available and printed the work of many black writers and campaigners. It was also the venue for cultural and campaigning events.

The George Padmore Institute is above the New Beacon bookshop on the first and second floors.

It was mind blowing and inspirational for me to learn about this brilliant man. He achieved so much. I really like the sound of him and the way he made things happen and helped people to come together to challenge injustice.

Garrod is a great storyteller and has lots of photos and objects to bring these important black histories to life.

She said: “It’s my job to look after the collection and to work with people who want to find out about and use the materials in it. I spend most of my time working with researchers, including writers and artists. Some want factual information but others like to browse the archives for inspiration.”

An example is artist Steve McQueen, who drew on material in the archives for his Small Axe films. The institute invited author and artist Ken Wilson-Max to be a writer in residence. He researched the archives to produce children’s books.

Better placed for access

I asked Garrod if the archive had worked with people with learning disabilities before.

“I don’t think we have – that’s not by choice but just the way things have turned out. Poor physical access to this building perhaps made us worry about how best to share our materials but there is always a way round this,” she said.

“We would love to be able to do more going forward and now the collection is catalogued we are in a much better position to find and share all accessible items.

“It’s a great time to start and we can work together to find the best materials and places to use in response to interests and requests.”

She added: “We want to make our black history collection available to people with learning disabilities, their families, teachers, staff and supporters.”

Garrod says anyone wanting to visit can make an appointment and staff will enable them to access the collection. This may include making arrangements to visit with a support worker, meeting in a different location or sharing materials online.

So far, Garrod, Ledger and I have been working together to create easy-read materials for two sections of the archive. We plan to share more about this work in a future issue of Community Living.

Connections between our lives today and black history continue to really matter. It is important for people with learning disabilities who are interested in working to stop racism to make links between anti-racism campaigns led by black people in the 1960s and 1970s and those of today.

Many people living in the community are often, in reality, housed in mini institutions. We need to think carefully about what we mean by an ordinary home, says Lucy Series.

After my son was born two years ago, I had to stay in hospital for a while. Despite fantastic care on the delivery ward, the postnatal wards were grim, particularly during Covid.

Us mothers were ruled by an institutional clock that dictated when we slept (rarely), woke up (early), got pain relief medication (not until the trolley came around) and when we should be up and about, regardless of pain.

Some midwives and auxiliaries were kind, but others approached us as problems to be managed, patronised, perhaps even punished.

Nobody even bothered to tell us when the hospital decided to ban our partners’ visits.

Late one night, in pain and distress, I discharged myself.

Arriving home, I was struck by the contrasts: here was a place where I felt loved and safe, and belonged.

Welcome home bunting on the wall, a bed made up downstairs until I could manage stairs, mince pies by the fire, tea in my favourite mug, the cat curled up next to the baby’s basket.

Pain relief when needed, not on somebody else’s clock. The privacy to cry, yet people around for support.

I could rest, relax and enjoy the new addition to our family. When I took a turn for the worse later that week and was offered a hospital bed, I preferred to stay at home.

This powerful contrast between the inner workings and subjective experience of an institution and the life I enjoy in my home came shortly after I finished writing a book, Deprivation of Liberty in the Shadows of the Institution

The book tells of how, not so long ago, hundreds of thousands of people spent their lives in large institutions. These ranged from 19th century asylums and workhouses to 20th century “mental deficiency colonies”, later called “mental handicap hospitals”.

Sociolegal historian Clive Unsworth calls this the carceral era. During the second half of the 20th century, these large institutions were gradually closed and the buildings demolished or repurposed.

People now lived in the community, in a variety of settings from care homes to supported living, with some in an ordinary house or flat.

Unsworth called this the post-carceral era, an era of policies and initiatives promoting ordinary or normal lives in homes in the community, elevating autonomy, independence, person-centred care and choice and control.

The problem is that many people living in care homes, supported living or private homes do not enjoy the autonomy, independence, person-centred care, choice and control the pioneers of community living aspired to.

Some do – and we need to hold on to this, because realising this for everyone should be the central aim of social care.

The dismaying reality is that many community settings are, in effect, mini institutions.

In care settings, we talk about personalising space precisely because of a background assumption of depersonalised, institutional spaces

More people are detained in Britain’s care homes than in its prisons. There are more than 80,000 people in prison in England and Wales. In 2021-22, there were 88,960 applications to authorise deprivation of liberty in nursing homes and 80,225 from residential care homes – a total of more than 168,000 applications.

While local authority backlogs meant not all the applications were authorised and some may relate to the same person, it is clear that a huge number of people are categorised as deprived of their liberty in care homes.

The problem is that we regularly conflate “homes” with “institutions”. We hope that, by calling a place a home, it sets us apart from our carceral past yet, often, the inner dynamics remain institutional.

This presents problems for courts and regulators in deciding whether a place is a private home or regulated premises.

It also means that, as community living advocates, we need to think deeply and carefully about what we mean by “ordinary homes”.

Homes and institutions are different kinds of jurisdictional space. Jurisdiction means the power to speak the law – that is, to lay down or interpret and apply the rules.

Homes are quasi-sovereign jurisdictions, where those living in them lay down the rules: an Englishman’s home is his castle. Institutions are governed by authorities, not those living in them.

This is illustrated by the Rampton smokers’ case (R (N) v Secretary of State for Health, R (E) v Nottinghamshire Healthcare NHS Trust [2009] EWCA Civ 795).Patients in high-security Rampton Hospital challenged the smoking ban, arguing that the hospital was their home so they should be allowed to smoke there.

Judges were sympathetic but observed that the freedom to do as one pleased varied depending on where one was. Although an activity might be protected from arbitrary interferences in a private home, similar protection would not apply to patients in public hospitals.

Homes are associated with autonomy, privacy and a locus of control. People living at home decide who invite in and have the freedom to come and go as they please. Small, everyday choices, such as smoking, are important. It is well documented that the erosion of such micro-choices is damaging to wellbeing and health.

So, when deciding whether a place is really a home, we should ask: does this person enjoy privacy, and have the freedom to make everyday decisions and control the threshold? Who, ultimately, makes the rules in this place?

Home is also a place of belonging and rootedness. In contrast, institutions tear up our roots and can restrict, threaten or even sever our critical relationships.

If we want a place to be a real home, we should ask whether the person is living with others they want relationships with, are able to enjoy other critical relationships fully and are free to form new relationships and offer hospitality.

And is their home in a community or truly part of one?

Homes are critical spaces for expressing and sustaining identity. Yet, in care settings, we talk about personalising somebody’s space (usually just their bedroom) precisely because of the background assumption of depersonalised, institutional spaces.

Nobody living in a regular home talks about personalising their bedroom. Yet there is an entire industry devoted to making care services look more homely. But these are simulacra; no amount of carefully positioned doilies and knick-knacks can replicate the subtle, complex and idiosyncratic aesthetics of a genuine home.

What is a home?

So what, then, is a home, and how does it differ from an institution?

The difference does not lie in the buildings, nor in legal or regulatory status, nor in what other people want to call it. Homes, as I argue in my book, are critical decision spaces for the flourishing of the self.

They are places where we are can critical decisions about where we live, who we live with and who comes into our home to support us – the kinds of decisions reflected in the right to independent living under the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities – as well as the everyday micro-decisions that make up our lives, our selves.

Being able to make critical decisions brings a sense of privacy, safety, connectedness and belonging.

Even people who are unable to decide under mental capacity law still have agency. They can still express what brings them happiness, connection and a sense of safety.

They still weave patterns of meaning into the world around them. A meaningful home for them – as for everyone – is living arrangements that reflect and sustain that.

Lucy Series is a lecturer at the School for Policy Studies, University of Bristol

Grace Currie: artwork; Helter Skelter: photography

A BBC comedy drama looks at married life for a couple with Down syndrome, and a former boy band star is inspired. Simon Jarrett holds the remote.

In the A Word, an excellent BBC series featuring a Lake District family with an autistic child, two fairly minor characters with Down syndrome got married.

They are now the subject of a spin-off series, Ralph and Katie. Ralph and Katie Wilson (Leon Harrop and Sarah Gordy) are settling down to married life.

They live in the same Lakeland village, but have engaged a support worker and have their own place, complete with interfering neighbour and worried parents constantly knocking on the door.

Let’s first celebrate the fact that there is a six-part, prime-time BBC comedy drama exploring the lives of people with learning disabilities seriously with empathy and humour. I could not have envisaged that happening even 10 years ago.

Second, once the series hits its stride (in my opinion around episode three), it engages with important issues using a light touch without feeling boringly worthy.

In one striking episode, Ralph is confined to the sofa with his leg in a cast. The house fills with concerned family members, the support worker, a neighbour and friends, and starts to resemble a care home as everyone scurries about trying to “help” while ignoring Katie and reducing Ralph to a helpless patient.

Parental anxiety and the struggles of the couple to adapt to married life, exacerbated by obstacles from having a learning disability, are strongly woven into each episode.

There have been some Twitter mutterings about there being more people with Down syndrome in TV roles than those with other learning disabilities. However, this criticism is churlish when we have waited so long for any visibility on TV at all.

Also, Harrop and Gordy are highly trained, accomplished actors who have been working professionally since their schooldays. Each has faced rejection and prejudice. They were not parachuted in by a director who fancied featuring people with Down syndrome and found, miraculously, that they could act.

There is much to relish in this lively, intelligent, good-hearted series, its talented stars and the high- quality ensemble around them.

In I Used to be Famous, Vince (Ed Skrein), a faded boy-band star, is drifting into middle age in bedsit land broke, depressed and forgotten. It’s 20 years since he last performed. Hawking his synthesiser around pubs, he has doors slammed in his face.

When he is reduced to busking on a bench, a teenager appears behind him and starts to play along using his drumsticks and, to Vince’s surprise, is pretty good. This turns out to be the autistic Stevie (played by neurodiverse actor Leo Long).

The rest of the movie tells the story of their complicated relationship and collaboration.

Netflix has designated this a feelgood movie, so you know the drill. However, all have a bumpy ride to get there and the film has some interesting things to say.

Feelings of guilt and grief drive Vince’s unhealthy saviour mentality over his protégé. Amber is terrified her son will get hurt if she lets go. Stevie is often crushed by everyone else’s anxieties and assumptions.

Worth a watch, despite its clichés.

Ralph and Katie

iPlayer

I Used to be Famous

Netflix

In this edited extract, Richard Keagan-Bull recounts visiting Auschwitz. His autobiography covers many other travels, living in a L’Arche community for people with living disabilities and growing up in the 1970s as people were increasingly being given a voice.

In an extract from Don’t Put us Away: Memories of a Man with Learning Disabilities by Richard Keagan-Bull, the self-advocate and university research assistant describes a disturbing trip to Auschwitz.

I went to Poland with two other people with learning disabilities and three assistants from our community for our summer holidays. I had heard about Auschwitz and really wanted to visit.

Jacek was visiting his family in Poland at the time and joined me for the visit to Auschwitz. It was just me, one of the assistants and Jacek who went.

I found it very moving. Just walking around and looking at some of the things there.

What shocked me the most was that everyone had labels pinned to their prison uniforms and I asked Jacek, my friend, what label I would have had.

I don’t think I would have been here today, nor none of my friends. I think that if I were there they might have decided to do some tests on me in their so-called “hospital room”.

And I was just so pleased that there was me from England, Jacek from Poland and the female assistant who was from Germany all standing there – together, and I just ask that we try and learn from our mistakes and that this never happens again.

It made me quite angry it did, and I wanted to kick something I did, but with a lady being there I felt I shouldn’t do that.

I feel quite angry inside now I do – about the way they were treated like cattle – like they weren’t worth anything. I can see now why people who lived through that, when they see those uniforms, they feel sad and angry.

I think in life we should try and understand each other and work things out and never want war – just be happy with what we’ve got. It doesn’t matter if you’re black or white, if you can speak or if you can’t speak – it’s what you can give that counts.

Don’t Put us Away: Memories of a Man with Learning Disabilities by Richard Keagan-Bull is published by Critical Publishing, 2022

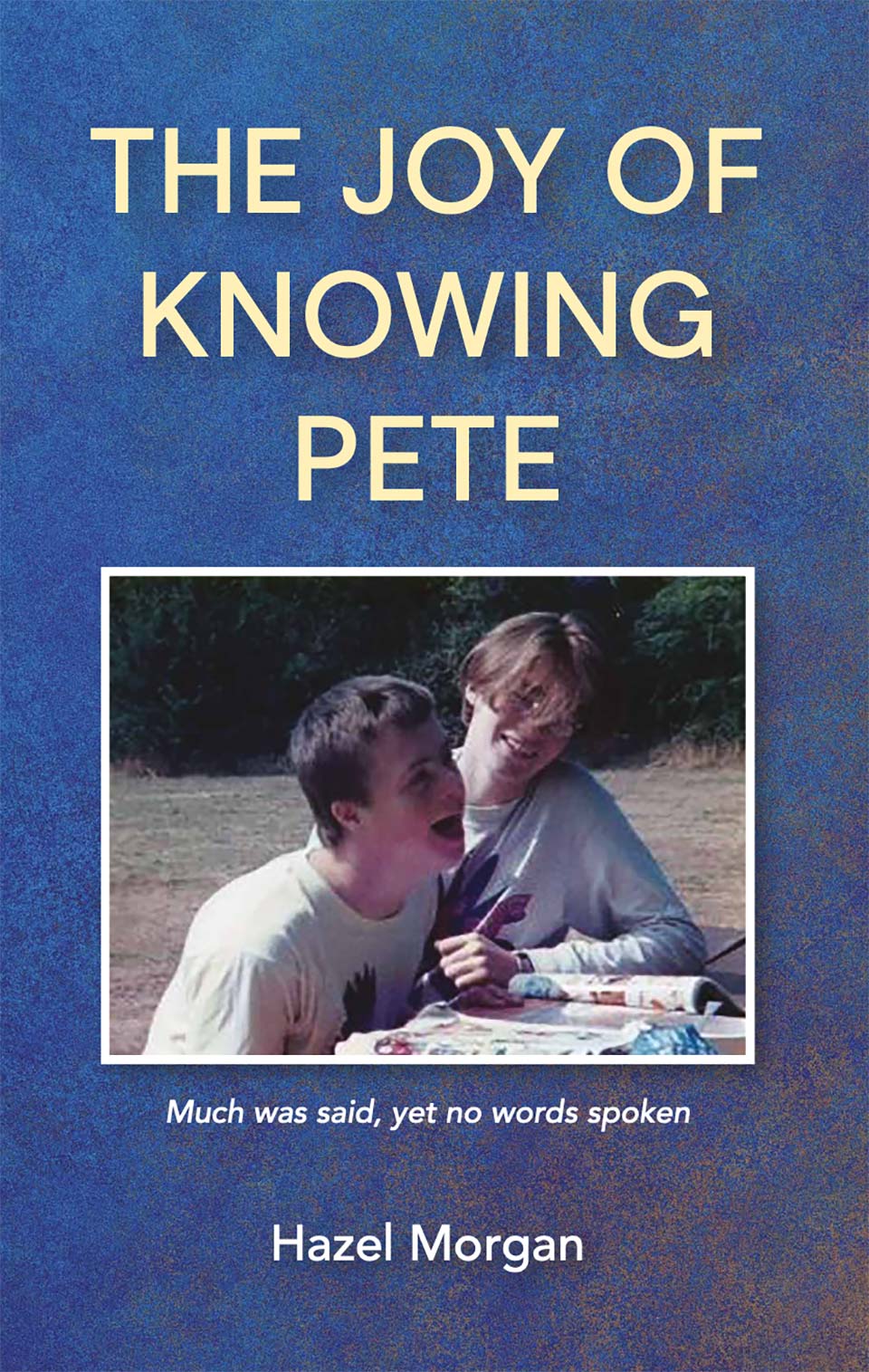

Michael Baron follows the ups and the downs of loving a child with profound and multiple disabilities.

“Do not despair,” seems to be her message, for Pete is a joy throughout his short 18-year life. Morgan tells it all in a book about love and sharing the good and the bad – a memoir of the ups and the downs of loving a child with profound disabilities.

Read Morgan’s book for her insight into her son’s likes and dislikes, and his real appreciation of the changing world about him.

An example is Pete’s hatred of snow, and how it interfered with his delight in walking. His satisfaction with life is shown in the progression from first days in school to his last weeks in the Chantry, a Sue Ryder specialist neurological care centre in Ipswich. There he received wonderful care in what was, apart when he was from living with his family, his final home.

This book is permeated with lessons on how parents and siblings live with disability. Morgan does not write like the Oxford graduate she is but tells us straight how it is an experience like no other.

Parents and siblings will read how the Morgan family coped; Pete’s days and nights at home, the holidays, interactions with the wider family, the schools, the travel by train and car, and the last days.

The family coped and they cared, and it was within the bosom of a loving church. We may well wonder at the role of the church in general but, in the Morgans’ case, not this church. It was an important part of Pete’s story.

His parents could judge this – as with so much else – from the non-verbal Pete. The subtitle of Morgan’s book is: “Much was said, yet no words spoken.”

His death touched so many that at the end, the sad event filled the pews. This is a fine memoir which repays the reader a hundred fold.

Pete we shall remember.

The Joy of Knowing Pete by Hazel Morgan is published by YouCaxton Publications, 2022

A short story by Jack London’, written from the perspective of an institution resident who describes his thoughts, feelings and dreams, was hailed as groundbreaking, says Susanna Shapland.

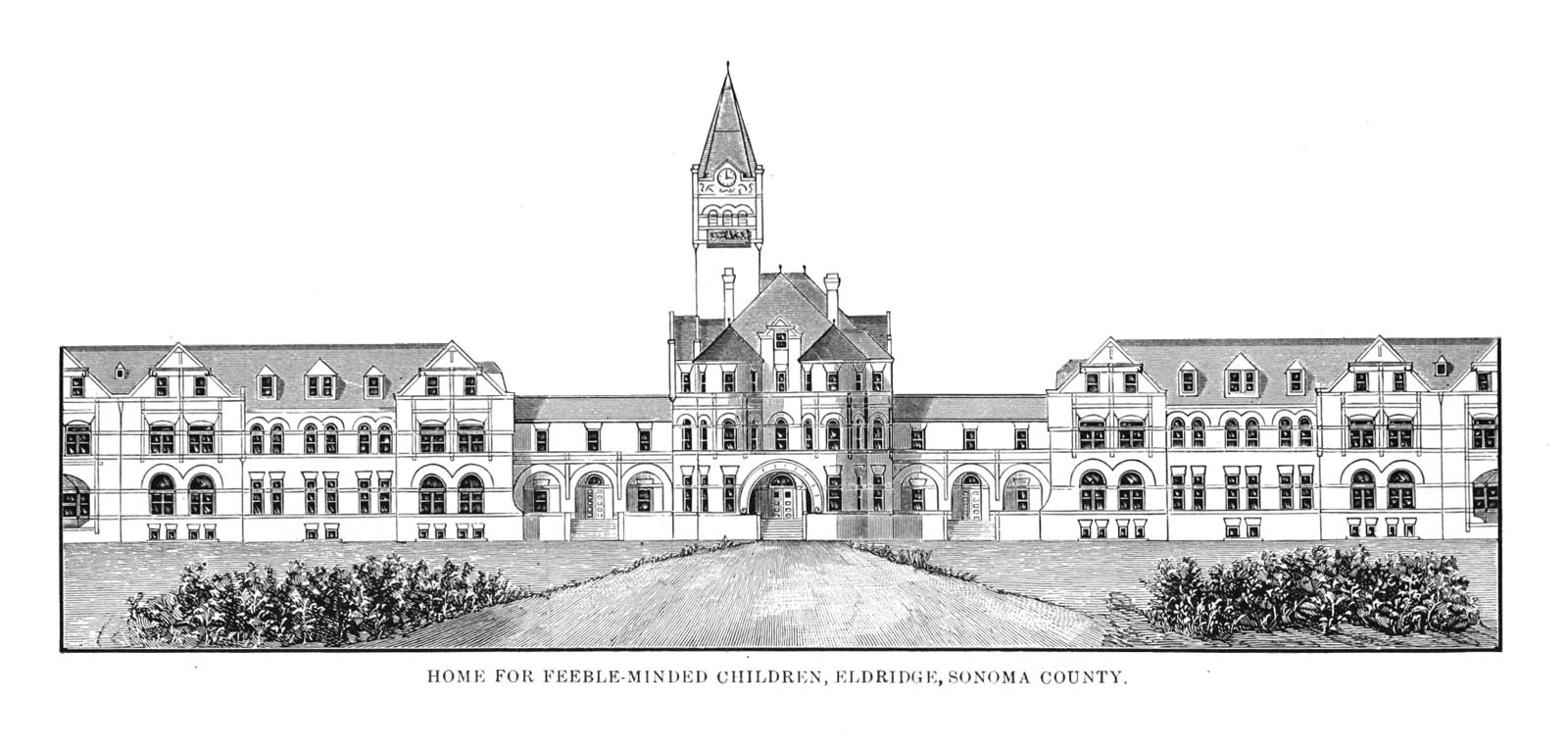

Sonoma State Home – image: State of California

American author Jack London (1876-1916) is best known for his adventure stories, such as The Call of the Wild.

In his later years, he moved to Beauty Ranch in California’s Sonoma Valley, and experimented with different styles and genres.

This was when he wrote Told in the Drooling Ward, a short story narrated by Tom, a long-term resident of an institution for the learning disabled.

The story has been praised as unique in terms of style and subject matter within both London’s canon and contemporary fiction. Telling the story from Tom’s viewpoint was seen as groundbreaking. Moreover, he is vividly drawn, with thoughts, feelings, hopes and dreams.

He considers himself high up in the hierarchy of “feebs”, as he refers to the “feeble-minded” residents, and has important duties.

He also feels he is superior to some of the staff, believing he has a better sense of how to interact with other residents – although this does not quell his desire to marry a good number of the nurses.

Just as London was inspired to write The Call of the Wild by spending a year in Yukon, the ideas behind Told in the Drooling Ward likely came from his surroundings in California.

Beauty Ranch abutted an institution for the learning disabled known as the Sonoma State Home.

London’s sister Eliza managed the ranch and occasionally hired residents as day labourers. London and his wife Charmain regularly visited the home, getting to know both staff and residents.

In 1911, London sent a draft of Told in the Drooling Ward to the medical superintendent, Dr William Dawson.

Dawson wrote that he found it “in greater part to be true to life”, and even surmised that Tom was based on “our old inmate, Newton Dole”.

The real home was established in 1891, after two mothers of “severely disabled children” wanted to found “a school and asylum for the feeble-minded, in which they may be trained to usefulness”.

For Tom, the home provides asylum: his continued residency is a conscious choice, preferable to the outside world where he has faced cruelty and violence.

London pushes the narrative that Tom is happier and safer inside the institution, which is brought home to him whether fleeing from a brutal adoptive family or returning from an abortive attempt to find a gold mine.

Literature professor Don Graham suggested that the Endicotts, a lightly fictionalised version of Jack and Charmain London encountered by Tom, were included in the tale “to represent the unfeeling attitude toward the feeble-minded held by the general public”.

Whether that is the case, it would be wrong to suggest that unfeeling attitudes did not affect the fictional or the real-life home.

For example, Tom’s frequent plans to marry every nurse who shows him the slightest affection are always thwarted by the fact that, to the nurses, he is a “feeb”.

This attitude is endorsed by the home’s policy that “feebs ain’t allowed to marry”. In real life, residents experienced brutal restrictions under eugenics laws, which often mentioned the home by name.

More than 5,000 residents “believed to be inappropriate for childbearing” were sterilised between the 1920s and 1950s.

Dr Frederick Otis Butler, medical superintendent for most of this period and who performed over 1,000 of the sterilisations himself, said: “If a child cannot be born of normal parents, it is better not to be born – for the child’s sake.”

The home closed in 2018.

London J. Told in the Drooling Ward. https://tinyurl.com/yjh3bvff

Graham D. Jack London’s tale told by a high-grade feeb. Studies in Short Fiction. 1978;15(4):429-433

When healthy people die in their care, providers – and this includes charities and community support – should engage with families and apologise, says Alicia Wood.

While Covid restrictions are lifted, some people need more protection as they have complex health needs - Alissa Eckert/Dan Higgins/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Christy Lawrance

Kamran Mallick, chair, VODG Commission on COVID-19, Disablism and Systemic Racism – photo: VODG

People with a learning disability from an Asian or Asian British background were three times more likely to die from Covid than their white British counterparts, research has shown.

The Voluntary Organisations Disability Group launched its Commission on Covid-19, Disablism and Systemic Racism last summer. The commission, funded by the Joseph Rowntree Trust, has gathered views from people, families and carers.

It also aims to explore how the long-term neglect of social care has had negative outcomes.

Commission chair Kamran Mallick, chief executive of charity Disability Rights UK, said: “The evidence cannot be ignored and compels us all to learn from these experiences, to collectively seek out solutions and identify what must change.”

Few studies on the pandemic have involved those with learning disabilities but people are now working with academics to highlight issues and ideas for change, says Gary Bourlet.

While Covid restrictions are lifted, some people need more protection as they have complex health needs - Alissa Eckert/Dan Higgins/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Christy Lawrance

More than two years since the pandemic began, the winter season and new Covid variants are on the horizon.

This has led members of Learning Disability England (LDE) to discuss the virus’s impact on people, family carers and organisations providing support.

During the first year of the pandemic, Public Health England figures showed that people with a learning disability were six times more likely to die as a result of Covid than the general population.

But, while Covid has sparked many studies, there are few in which people with learning disabilities could easily be involved.

So LDE, a national membership organisation uniting people with learning disabilities, families, friends and paid supporters in a movement for change, partnered with researchers from 12 universities to do just that.

The Coronavirus and People With Learning Disabilities Study, launched in October 2020, is exploring how the pandemic has changed lives. It is drawing on the views of almost 1,000 people with learning disabilities across the UK plus 500 family carers and paid support staff.

LDE has been involved in the research in England, which has so far highlighted the most important issues for policy and practice in seven key areas. These are: jobs and money; mental health and wellbeing; services; health; using the internet; information; and the experiences of people and families with higher support needs.

The discussions and ideas for change emerging from the research have been wide ranging.

“Some people have said that they felt sad or down often or always,” says Tanya Woodhouse at user-led charity Connect in the North. “People with learning disabilities need better advice about mental health.”

A self-advocate at Lancashire charity Pathways says: “It’s OK sending out information in lots of different accessible formats but, at the end of the day, if it’s not the information we want and need, it becomes meaningless and actually wastes resources.”

A member of the Gr8 Support Movement for support workers said: “We’ve got to think more holistically and globally about supporting people. And who can do what best. There’s a little glimmer of hope that maybe people will be a bit more aware in the future.”

There needs to be a cultural shift that supports the idea of access to communication and connectivity as a human right.

Crucially, the research has explored how people, families and the organisations that support them felt when government lifted the last of the Covid restrictions on 1 April 2022.

Many LDE members have raised concerns that some people with learning disabilities are still at higher risk if they catch Covid. This is because they have weaker immune system or complex health needs, so Covid is still having an impact on their lives.

“It affected both me and David and his dad. That we were very, very frightened.

I still feel that way,” says Linda Storey, a family carer from Rotherham-based advocacy group Speakup.

John Casson, chief executive at national support provider L’Arche, notes: “We cannot let Covid turn back the clock for disabled people. The Covid response told people with disability: ‘You’re different – a patient to look after, not a person. A problem to manage, not a citizen.’ So how do we go forward, not back? We have learnt in L’Arche it can be done – if we trust people and empower them to make the decisions for their lives.”

Right now, the single biggest worry for LDE members as we move towards winter is the availability of the right support.

Jordan Smith co-chairs LDE’s self-advocate representative body, part of its main rep body, which is made up of self-advocates, families and professionals. Smith says: “We know lots of staff are going the extra mile to make sure people are supported – our members have told us. But difficulties in recruiting and retaining staff mean too many people are not getting the support they need to live good lives.”

Kate Chate, a family carer from Suffolk, said: “There is a crisis in recruiting and retaining people to support the people we love. Families have been scaffolding the care system throughout the pandemic and will not be able to manage to continue without respite.”

The research team is now carrying out the fourth wave of its work, with findings due to be published in early 2023.