Neil Carpenter’s book puts benefits on trial

When she was eight, Denise had the first of what turned out to be many epileptic seizures. Because of the way in which they have affected her memory, she cannot remember much of the detail of her life after the seizures started or what her life was like previously.

A member of staff at her day centre, however, who went to the same secondary school, recalls both appalling bullying there and later, when she was nearly 20, a sexual assault that went to court. Not the start in life that most of us enjoyed and one that cries out for compassion.

Instead, the state inflicted the reverse upon her. Where it should have helped someone like Denise after her experiences in childhood and adolescence, it instead intervened through the Department of Work and Pensions (DWP) to make her life even worse.

Denise, now in her early 50s, attends a day centre and lives with her husband – who also has a learning disability – without any support at home.

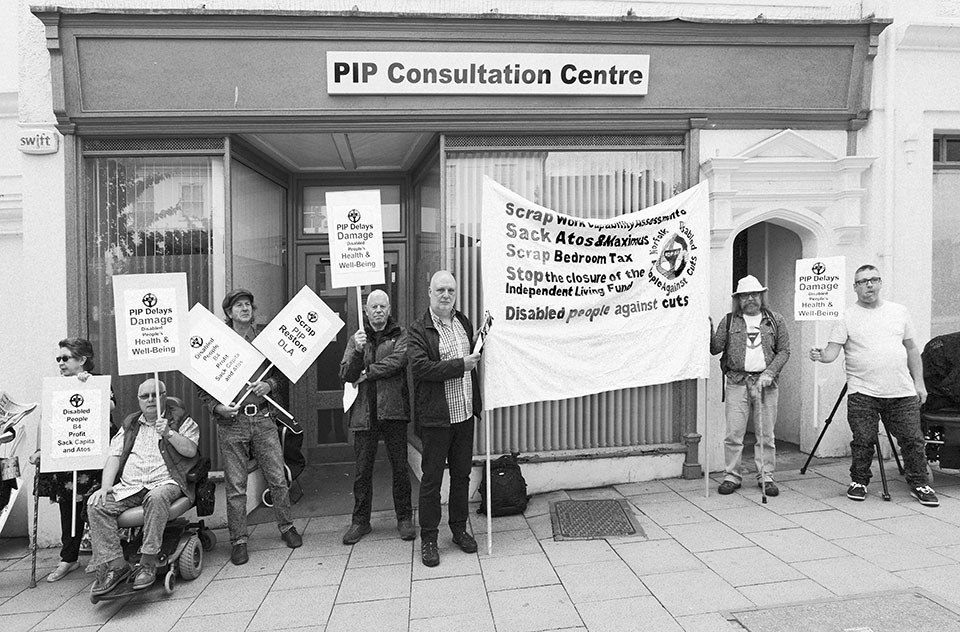

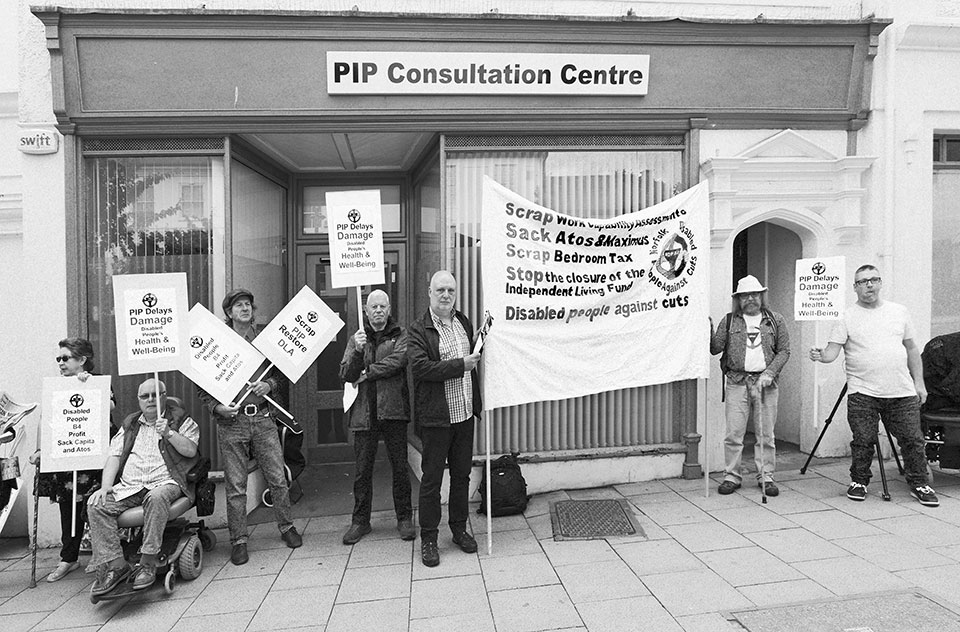

Delays in personal independence payments damage the health and wellbeing of people with disabilities, as Disabled People Against Cuts make clear in a protest in Norwich – photo: Roger Blackwell/Flickr/CC BY 2.0

She, like all the others in my new book, Benefits on Trial, was turned down for a personal independence payment (PIP), and left with an income on which no one should be asked to survive.

Denise’s situation was made far worse by the fact that her husband, George, had no income and therefore the money she received had to provide for two people.

Her £107.50 in 2018 was only 26.86% of the UK median per week, 28.27% of the equivalent median for the south west and 39.99% of the Joseph Rowntree Foundation’s UK minimum income standard – in the foundation’s words, “what you need in order to have the opportunities and choices necessary to participate in society”.

Its attritional approach – a key part of DWP culture – grinds people down until they lose the will to fight back.

The tribunal decision in Denise’s favour came in 2020, three and a half years after she had first been turned down for PIP.

Benefits on Trial, published in February this year, describes Denise’s prolonged fight to transfer to PIP and is based on my work in Cornwall since 2012 as a volunteer advocate with adults who have a learning disability.

In recent years, that work has increasingly concerned benefits cases: helping people with their applications for PIP and employment support allowance (ESA); accompanying them to assessments; requesting reconsideration of decisions; and taking cases to the tribunal stage. Those experiences – particularly of tribunals – triggered the writing of Benefits on Trial.

My book describes how six people have to battle with the DWP whose system, with built-in hurdles, is loaded against them. Benefits on Trial builds up a detailed picture of their current lives and the past events that have helped to shape them.

The experience of Denise – her early years and her applications for benefits – serves as an example of the inhumane treatment suffered by all six at the hands of the DWP.

A key part of Denise’s prolonged fight to transfer to PIP was countering the distortions of the DWP; for example, her assessment and subsequent references to it misrepresented her learning disability.

Even though evidence was given in the medical records we had submitted, there were three references in the pack of appeal documents that cast doubt on her disability. One of these – “You do not have a diagnosed sensory or cognitive impairment” – illustrates how distorted the DWP representation of her condition was.

At Denise’s appeal, which was heard in June 2020, the outcome was successful. Having been given no points in the original decision and at the mandatory reconsideration stage (where a claimant can challenge a benefit decision), the tribunal panel gave her 11 points for the daily living component and 10 for the mobility component, resulting in a standard award in both areas.

The fact remains, however, that the tribunal decision for Denise came three and a half years after she had first been turned down for PIP.

Over those 42 months, she had been confronted by all the hurdles created by the DWP and had fallen initially at several of them, only to pick herself up again and again.

Success, a small compensation

For this long, drawn-out period during which she endured acute stress that triggered panic attacks, she had been left – with no follow-up enquiries from the DWP – in a state of relative poverty. A successful tribunal decision is small compensation for what she had suffered.

Such success at the tribunal stage is typical of the cases I describe in Benefits on Trial.

When the DWP has turned down benefit applications and left people in relative poverty, not once has it followed up the impact of its decisions.

Denise and the other people in my book are not isolated examples of injustice. The DWP’s most recent available statistics, covering three years from 2018 to 2020, show that the success rate of appeals against PIP decisions for people with a learning disability is approximately 90% of 890 cases.

Two of the individuals in Benefits on Trial figured prominently in my previous book, Austerity’s Victims.

Danny (see box at the end of this article) is nearing retirement age and has an acquired brain injury. Thomas is in his 40s and has Down syndrome. Both live independently but Thomas receives support at home from his mother and Mencap.

The others, along with Denise, are Ben, Jon and Tony. Ben, in his 30s, has fibromyalgia and ME as well as being on the autism spectrum. He, like Danny, attends a day centre and gets support at home from both a personal assistant and a care agency.

Jon, also in his 30s, has global developmental delay. After going to a special school and taking a special educational needs course at college, he now lives at home with his mother. Tony has a learning disability. He is in his 50s and lives with his wife, Jill. Both Tony and Jill are unable to read or write.

What should be done to tackle this injustice?

Above all, DWP culture has to change. After it turned down the benefit applications of the people in my book and left them in relative poverty, not once did it follow up the impact of its decisions.

This utter lack of humanity was justified by then secretary of state for work and pensions Thérèse Coffey in September two years ago to the House of Commons’ Work and Pensions Committee.

She asserted that her department had no such duty to benefit claimants but that duty should be left to “the local councils, the social services, the doctors and other people”.

Casual attitude

Such a casual approach to governmental responsibility, illustrated by the nebulous and throwaway term “other people”, is unacceptable.

Equally unacceptable is the attritional approach of the DWP – a key aspect of its culture – that attempts to grind people down until they lose the will to fight back.

If the DWP changes that attritional culture, so starkly seen in the treatment of Danny and Denise, specific aspects of the way it works then need to be tackled.

First, it must make constructive use of the information that is already available to its officials instead of, for example, ignoring previous tribunal decisions as if they had not happened.

Second, it must make reasonable adjustments instead of sending a 33-page PIP application form to someone such as Tony who cannot read and write.

Finally, the quality of assessors has to improve.

One question at Thomas’s assessment from the assigned health professional – a supposed expert according to government propaganda – was enough to demolish that expert status. His parents were asked of his Down syndrome: “When did he catch it?” The crassness of the question would be laughable if it were not so serious.

Until those changes happen – and obviously more are needed than the three I’ve mentioned – the DWP will stand exposed by the evidence in Benefits on Trial.

The current benefits system, with the sort of distortions that denied there was any diagnosed sensory or cognitive impairment in Denise, does not need minor tinkering; it needs to be replaced by one that takes fair assessment as its guiding principle.

If that happened, someone like Denise would not have to wait for 42 months, deep in poverty, to overturn a DWP decision to deny her PIP.

No change for decades – then DWP tries to cut and deny payments

The experience of Danny is typical of what so many undergo at the hands of the state. After a motorbike accident in 1980, he was in a coma for more than six weeks.

Once he had regained consciousness, he was unable to walk, crawl or sit up and had lost all memory of key elements in his life such as the school he had gone to.

Recovery was a painfully slow process. He had to relearn first how to crawl and then how to walk. From that point, it took several more years before he was able to move away from his parents and live independently.

He has been left with a number of health problems: vertigo, palpitations, an underactive thyroid and emphysema; his legs ache if he stands continuously for any length of time and walking any distance is a strain as a result not just of the aching but also because of groin and chronic lower back pain.

As a consequence, he sleeps very badly, with a resultant build-up of tiredness. Unsurprisingly, stress is a growing issue for him.

Despite all these problems and his benefits not changing significantly for more than three decades, in 2016 the Department for Work and Pensions tried – unsuccessfully – to take away his employment and support allowance.

That was followed three years later by the department trying – again unsuccessfully – to deny him a personal independence payment.

- First names are used here as in the book; all are pseudonyms

- Benefits on Trial by Neil Carpenter is available in print and as an e-book on Amazon

- See review

Neil Carpenter is an author and volunteer advocate