Sonoma State Home – image: State of California

American author Jack London (1876-1916) is best known for his adventure stories, such as The Call of the Wild.

In his later years, he moved to Beauty Ranch in California’s Sonoma Valley, and experimented with different styles and genres.

This was when he wrote Told in the Drooling Ward, a short story narrated by Tom, a long-term resident of an institution for the learning disabled.

The story has been praised as unique in terms of style and subject matter within both London’s canon and contemporary fiction. Telling the story from Tom’s viewpoint was seen as groundbreaking. Moreover, he is vividly drawn, with thoughts, feelings, hopes and dreams.

He considers himself high up in the hierarchy of “feebs”, as he refers to the “feeble-minded” residents, and has important duties.

He also feels he is superior to some of the staff, believing he has a better sense of how to interact with other residents – although this does not quell his desire to marry a good number of the nurses.

Just as London was inspired to write The Call of the Wild by spending a year in Yukon, the ideas behind Told in the Drooling Ward likely came from his surroundings in California.

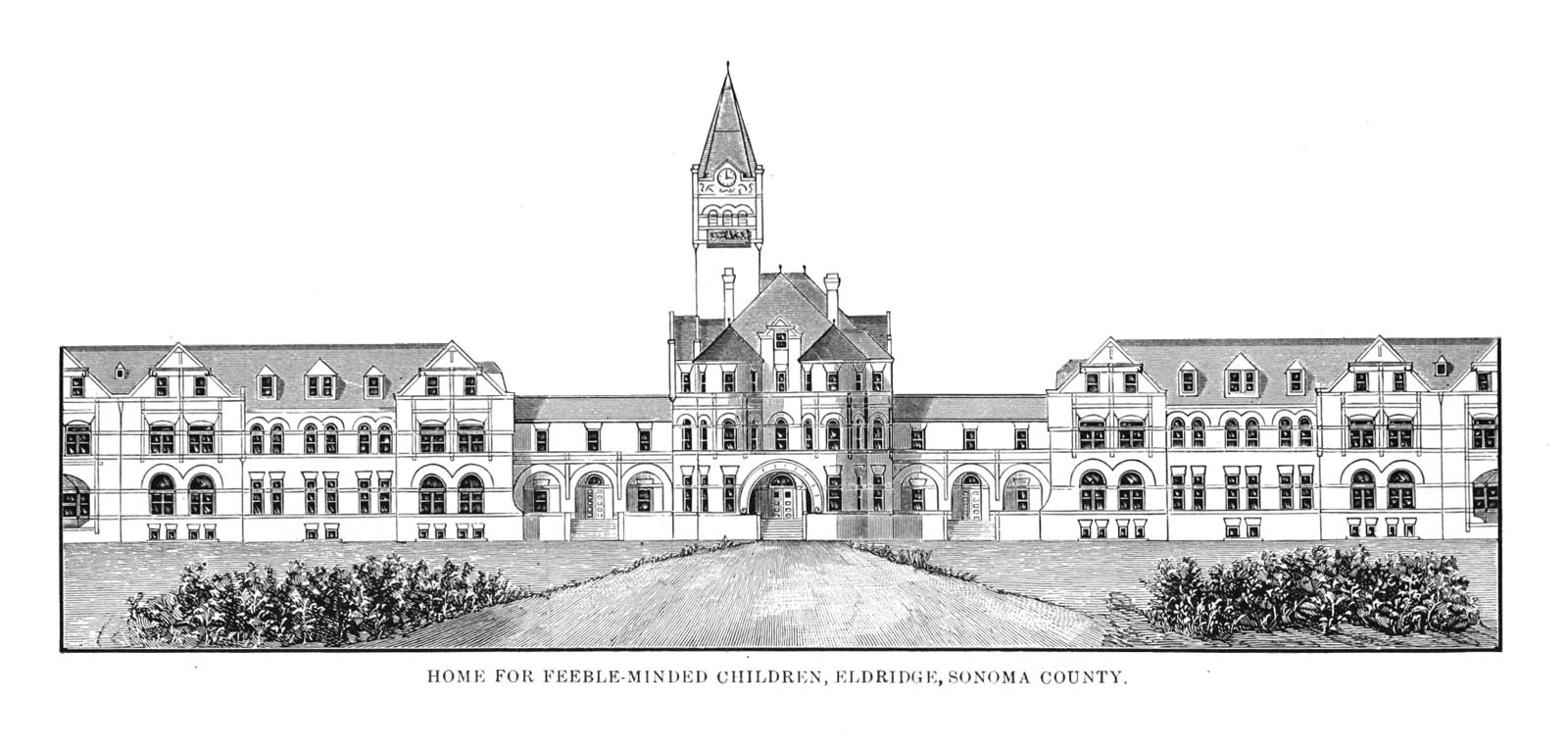

Beauty Ranch abutted an institution for the learning disabled known as the Sonoma State Home.

London’s sister Eliza managed the ranch and occasionally hired residents as day labourers. London and his wife Charmain regularly visited the home, getting to know both staff and residents.

In 1911, London sent a draft of Told in the Drooling Ward to the medical superintendent, Dr William Dawson.

Dawson wrote that he found it “in greater part to be true to life”, and even surmised that Tom was based on “our old inmate, Newton Dole”.

The real home was established in 1891, after two mothers of “severely disabled children” wanted to found “a school and asylum for the feeble-minded, in which they may be trained to usefulness”.

For Tom, the home provides asylum: his continued residency is a conscious choice, preferable to the outside world where he has faced cruelty and violence.

London pushes the narrative that Tom is happier and safer inside the institution, which is brought home to him whether fleeing from a brutal adoptive family or returning from an abortive attempt to find a gold mine.

Literature professor Don Graham suggested that the Endicotts, a lightly fictionalised version of Jack and Charmain London encountered by Tom, were included in the tale “to represent the unfeeling attitude toward the feeble-minded held by the general public”.

Whether that is the case, it would be wrong to suggest that unfeeling attitudes did not affect the fictional or the real-life home.

For example, Tom’s frequent plans to marry every nurse who shows him the slightest affection are always thwarted by the fact that, to the nurses, he is a “feeb”.

This attitude is endorsed by the home’s policy that “feebs ain’t allowed to marry”. In real life, residents experienced brutal restrictions under eugenics laws, which often mentioned the home by name.

More than 5,000 residents “believed to be inappropriate for childbearing” were sterilised between the 1920s and 1950s.

Dr Frederick Otis Butler, medical superintendent for most of this period and who performed over 1,000 of the sterilisations himself, said: “If a child cannot be born of normal parents, it is better not to be born – for the child’s sake.”

The home closed in 2018.

London J. Told in the Drooling Ward. https://tinyurl.com/yjh3bvff

Graham D. Jack London’s tale told by a high-grade feeb. Studies in Short Fiction. 1978;15(4):429-433