A life in the community – photo: Seán Kelly

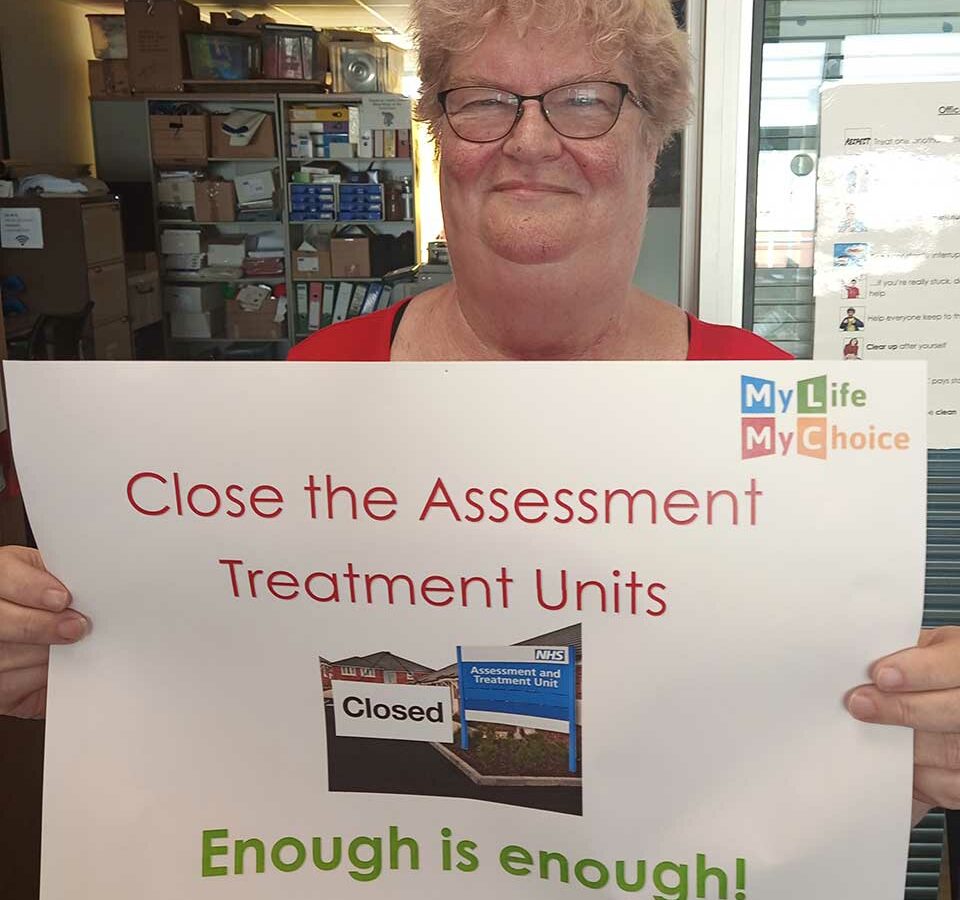

Alexis Quinn

Campaigner and author

People should enjoy the same opportunities as everyone else – the ability to live in a safe, comfortable home on a regular street and in a place of our choosing.

We should get to live with people we want to live with and have relationships and the chance of a family without scrutiny. If we want to work, go out to random places, stay up late and get drunk, we should be supported to do so.

Amy Tedd

Support worker, South Warwickshire

Having opportunities to build relationships, pursue careers and engage in hobbies and interests are essential to a good quality of life.

Stereotypes and prejudices, a lack of employment opportunities, inadequate funding for essential services and insufficient physical access are all huge barriers that inhibit a person’s right to a meaningful living standard.

Sarah Ford

Centre manager, Jolly Josh

Our Place To Call Home is a much-needed venue in Rochdale. We aim to meet the needs of those with additional needs, disabilities and profound and multiple learning disabilities, families and carers.

We’re proud we have a Changing Places [fully accessible] toilet. Regular or disabled toilets don’t meet the needs of the 250,000 people in the UK who require specialist facilities. Without these, it’s no wonder our families were previously isolated.

Joe Powell

Chief executive, All Wales People First

I’ve always wanted to be a taxpayer, to contribute to society. To be an active citizen. To reciprocate. To be a contributor, not a passenger. That dream became a reality when I was appointed national director of All Wales People First in 2012.

Unfortunately, I’m in a tiny minority. Most people are effectively retired and written off at 18 years old.

Human rights may be a major inconvenience to the government when legislating. But that’s exactly the reason we need them.

Dr Rashmi Becker

Sibling and Step Change Studios founder

An ideal community life for my brother would involve inclusive services and spaces. I’d like him to be able to access healthcare, housing, leisure centres, restaurants – public spaces and services where people are empathetic, kind, inclusive.

Simple adjustments can make a huge difference. Everyone can play a role, from the doctor making time to engage with him without preconceptions to the waiter at the cafe who’s always so welcoming. It’s not complicated – we just have to care.

Jo Sullivan

Chief executive, Superstar Arts

It’s an important part of our ethos that we deliver projects in a setting that shares space with other community groups.

This enables a truly integrative, inclusive experience, which leads to positive, productive community relationships.

We aim to create a supportive environment where adults express themselves via different creative outlets including exhibiting in local galleries and collaborating with mainstream artists and performers. It’s a successful way to challenge perceptions, and creates a great sense of belonging.

Simon Richards

Ambassador, Stay Up Late

In the past 10 years, I’ve gone from a person who mostly stayed in in the evenings to a person who is often out and about, at a karaoke or open mic night or at my drama group rehearsing for our next show.

I’ve been in supported living for a few years and I’m proud of the fact I can travel independently and safely to venues.

Anna Severwright

Co-convenor, Social Care Future

As I am a disabled woman, community living is more than just physically living in a community – it means I can be as active a member of my community as my non-disabled peers.

It means feeling welcome, that barriers (physical and attitudinal) are removed and any support I need to engage and contribute is available in the way I choose.

They’re the same things that matter to everyone as laid out in the Social Care Future vision: “We all want to live in the place we call home with the people and things that we love, in communities where we look out for one another, doing the things that matter to us.”

Jim Blair

Consultant nurse in learning disabilities

The right to be engaged in society should be afforded to all, whether you use words or not, whether you fit inside the designated societal margins or not.

Each person has abilities, talents and skills, and should be deemed a contributor.

We need to see people and their families in real positions of power and authority with the ability to be change agents.

Dr Sam Smith

Chief executive, C-Change Scotland

What makes a successful life in the community for people with learning disabilities is largely the same as for everyone else.

Having space and a place where you’re loved and respected for who you are, where you can grow and become your own good self. Where you spend time with people you know and care about, and who know and care about you. Where you can live life by a rhythm that suits you, going to places you like to go, doing things you like to do. Where you feel safe and part of something bigger.

Jolanta Lasota

Chief executive, Ambitious About Autism

As a society, we should all have high aspirations for what autistic young people can achieve. Like everyone, they should have employment, education or training opportunities that enable them to live an active life as part of the community of their choice.

Early intervention, education and support play a key role in preparing people for the life they wish to lead.

Within our schools and college, we work with young people and their families to understand their interests and ambitions and to develop skills that will enable them to have a quality of life they deserve and are entitled to.

Dr Joanna Griffin

Parent carer, psychologist, author and Affinity Hub founder

My son, who’s 15, wants to go swimming, visit a cafe, walk the dog and see friends and family. He also needs to choose food from a supermarket, go the opticians, get the bus and be part of everyday life – something those who don’t have a learning disability may take for granted.

What supports us are inclusive, accessible facilities and a welcoming attitude. Education, awareness and representation helps. Those who stand out are the people who accept us as we are, with openness and patience.

Dr Simon Duffy

Director, Citizen Network Research

We live at a time of social isolation, where fear, poverty and prejudice have locked too many in their own little bubbles.

This isn’t about people with learning difficulties – our whole society is disconnected, insecure and distracted by consumerist dreams that are killing our planet. People with learning difficulties hold the key to a different vision of citizenship and community.

Community living must be about stepping up, daring to shake things up and creating new forms of social life, environmental action and political change.

Dr Ayesha Mahmud

GP and parent

As a parent, especially a Pakistani-British Muslim parent of a daughter with a learning disability, my aspiration is that she’s accepted as part of the community – able to live, work, socialise and enjoy life.

It’s my dream not to worry about what will happen when I’m not around. I hope people know she won’t just take but also give.

As a GP, making community living a success means ensuring reasonable adjustments, personalised annual health checks (which can lead to improved health outcomes) and that people are part of patient participation groups.