Recovery: Manni reassures Reuben his future is important and that he will find his role in society – photo: Eddy Pearce.

My younger brother Reuben sent me a text message in November 2021. It was a simple question with no question mark: “brother. do. you. love. me.” I knew instinctively that it was a cry for help.

Reuben had been isolated from everything he knew and loved, shielded in a care home in Dorset, hanging on for so long and his resilience was waning. His message got to the heart of the issue, in his typical direct way, without mentioning the actual problem.

I showed the message to my partner, Jack, and we both knew that I had to go and “bronap” him.

“Go and get Frodo out of there,” Jack said. Jack is the third member of our trilogy and the Samwise Gamgee to Reuben’s Frodo (I am Gandalf the Grey).

Reuben, 39, is the youngest of my three brothers and has Down syndrome. He had been living his best life with us in Andalucía, Spain, before he had a breakdown in September 2018.

What brought it on? Did his panic attack happen due to heat, caused by his isolation living in a foreign country and not speaking the language or by coffee-induced palpitations? A mid-life crisis? As a family, we tried to put him back together again.

I hoped the book would help him to find his voice again and realise his important role in the hearts and minds of others.

It was a roller coaster ride of ups and downs. He would get better and then helter-skelter back down to the depths of a depression. He became non-verbal. It was as if his life source had been sucked dry.

In an attempt to get him settled in a town we know and love, Reuben entered a care home in Dorset early in 2020, then Covid happened. He was totally cut off from us for months, only able to wave to our parents and the occasional visitor through his downstairs bedroom window.

His health, mental and physical, deteriorated at an alarming rate. He became a mere shadow of the person he used to be. The image of him staring through his window as photographer Eddy Pearce took a portrait for archival project Bridport Lockdown is harrowing.

So, in November, I isolated as best I could in Gibraltar and travelled to the UK, masked and paranoid. I bronapped him and we went into isolation in a friend’s cottage in rural Dorset.

We spent the following 26 weeks trying to get to the core of our brotherhood. My wingman was wounded, oh so wounded. He wouldn’t talk, he didn’t want to eat, go for walks; he only wanted to sit or lie down on his bed, hiding.

I spent every day trying to ease him out of his frightened state. I reached out for him but he was not ready to take my hand. Patiently, I waited.

Reuben’s learning difficulty means that his learning curve is less pronounced than mine or yours might be. A psychiatrist came to visit us to make sure Reuben was safe with me. The authorities were naturally concerned for his ongoing welfare.

As comforting as the visit was, the gentle expert explained that Reuben had suffered a regression and that there was only a 10% chance of “getting him back”.

As the psychiatrist drove away, still wearing his mask and PPE, I remember sitting on the garden path as my tears found the cracks between the paving stones. My brother! My best mate! He really is the fulcrum of my universe and I was thrown off kilter.

Together with my partner, who was stuck in Spain, family and friends, we began to create a safety mat of love and support that might enable Reuben to crawl out of his winter hibernation and walk the high wire with me. Everything appeared to frighten him. Everything was too far, too noisy, too bright, too difficult. Slowly, though, we began to find a way through.

With travel restrictions changing at an alarming rate, it looked like we would be alone for the holidays. I sent a message to Jack: “Please try and get back for Christmas!”

When he arrived, I knew I was no longer alone. I had my man back and together we could face the invisible enemy of Reuben’s sadness and anxiety, together.

Everything became easier. You see, in our little family, two’s a crowd and three’s company. My hobbits were together again and, as a united threesome, we could once more explore the valleys of middle earth.

On Christmas Eve, I looked on as they hugged and giggled on the other side of the table. Their embrace and seeing the flicker of light in Reuben ́s eyes was the only Christmas present I will ever need.

Hope was restored but only for a while. After the holidays, Jack was called back to work in Spain. The next day, the nation was locked down.

How long would this go on for? How were we going to get through this? I begged Reuben to talk. I begged him to try and get better. I begged him to find the colour in the winter greys.

Resources of brotherhood

We had to dig deep and uncover the resources of our brotherhood. I felt as if I had to enter Reuben ́s state of mind, to truly understand what it felt like to be a man with Down syndrome, hanging on to his identity in this confused and frightening world by the skin of his teeth. It was only on entering his state of mind that I could begin to identify a way out of the labyrinth.

It was through walking Dorset ́s footpaths in the bleak midwinter that we began to find a strength to face the future. On daily walks, I gently reassured Reuben that his place in this world still mattered. I convinced him that his future was important and that he would find his role in society.

It was hard for me to admit but it became clear the system had failed Reuben miserably. His needs had not been met. The care system’s reaction to the pandemic had left him emotionally exposed and damage has been done.

This was through no fault of their own, for they were simply trying to salvage their businesses and save lives. I get it. I really do. But, in hindsight, it could have all been handled so differently.

Reuben had basically sat in his room for three months, rarely leaving the care home. No one had connected his TV so he had no idea what was going on in the world. I will always salute his bravery and bow before his resilience. I think I might have sunk even lower had I been in the same situation.

When I bronapped him, he had no idea what a vaccine was and why the world was spinning into a lockdown. No one had thought to explain to him.

Perhaps they assumed his ignorance might have been his bliss. They clearly had no idea how intelligent he is. He was craving information. He was craving an explanation. His survival instinct was to shut down and enter a period of emotional hibernation.

Eight weeks after moving Reuben from the care home, a friend encouraged me to write our story. I had always written for pleasure so, true to my friend’s inspired advice, I woke up at 5am, lit a candle, made a cup of tea, took a notebook our mum had sent me for Christmas, wrote “brother. do. you. love. me.” on the inside cover and began writing.

The words tumbled out in torrents. Through writing, my thoughts gained order. The cracks in my coping mechanism began to narrow.

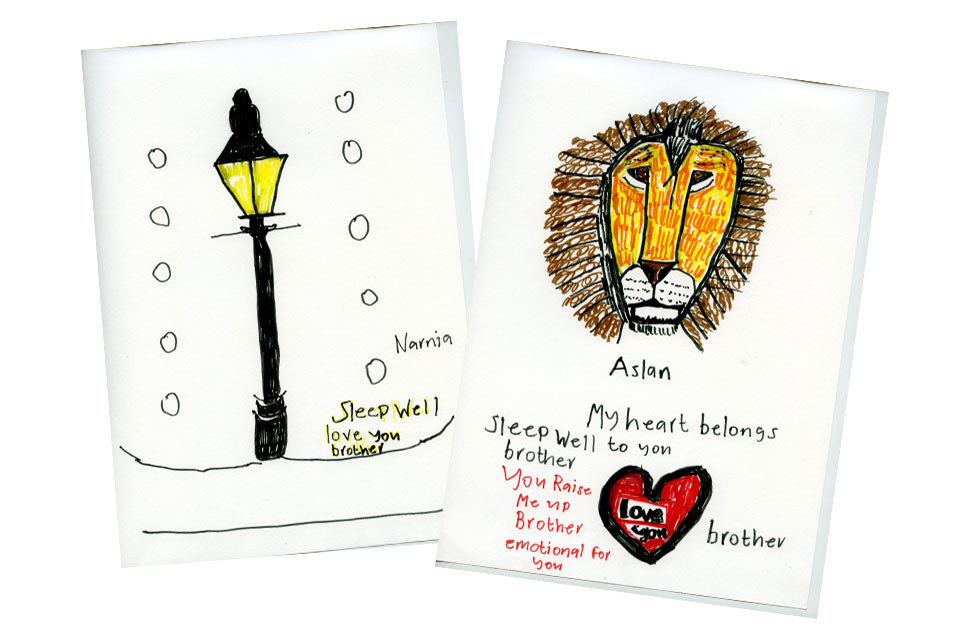

As I was writing, Reuben was drawing. Still non-verbal, he spent the afternoons drawing and would hand me his daily illustration every evening before he went to bed.

When Gracie and Adrian Cooper from independent publisher Little Toller Books heard about our book through a university friend’s Facebook page, they asked to meet us.

Reuben handed Gracie more than 200 drawings and Adrian began to read some of the manuscript. After a few minutes, they looked at each other and, instinctively, they knew. They offered to buy the book.

Reuben became more and more excited and involved in the project. It was always my hope that the book would help him to find his voice again and that it will help him to realise his important role in the hearts and minds of others.

Recovery: Manni reassures Reuben his future is important and that he will find his role in society.

We did it

Not long ago, he sent me a text: “you. me. did. it. brother.” Too right, brother. We did it. He continues to be my fulcrum and gives my life a clearer perspective, like a vanishing point that I use as a reference to draw all my lines.

Reuben’s text message had asked “brother. do. you. love. me.” This book is my response. Hopefully, he now understands just how much I do.

Brother. do. you. love. me. by Manni Coe and Reuben Coe was published by Little Toller Books on 4 October