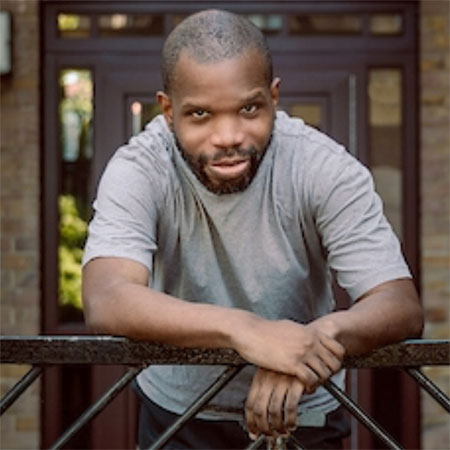

Paul Christian – photo: The Other Richard

As a black person with a learning disability, I’ve often wondered where I might fit as an activist. The lives and experiences of black British people like me are under‐represented in the UK history of learning disabilities. I am proud of my Jamaican heritage.

I have lived with the label of learning difficulty since I was a child, attending a special school before going on to train as an actor at the Royal Central School of Speech and Drama, and perform with London-based learning disability theatre company Access All Areas.

Following the brutal killing of George Floyd by police officer Derek Chauvin in the US, Generate Voices was formed. This is a group of people with learning disabilities, which is facilitated by London‐based community support and employment organisation Generate. The group came together to understand and take action against racism.

When I interviewed the group as part of my activism work, everyone highlighted a lack of accessible information about black history as a substantial problem.

At the same time, my own writing in support of Black Lives Matter for the Surviving Through Story Covid project (supported by the Open University) brought home how much information essential to understanding race and racism remains inaccessible.

These concerns have led to a collaboration with the George Padmore Institute to create easy-read materials for its black history collection. The institute is an archive and research and information centre in north London.

I met Sue Ledger in 2014 through Access All Areas and we started to research and write together. I am working with her on the easy-read project and she worked with me on this article.

Ledger is a visiting research fellow at the Open University and we both live in Hackney, an area of London with a diverse population.

When George Floyd was killed by police in the US, we both supported the Black Lives Matter protests that followed.

The archive collection at the George Padmore Institute is divided roughly into four areas.

Education

Records about the Black Education Movement (1965-1988) include photographs of schools for black children organised by black community members who were worried about the quality of education their children were receiving and their lack of access to black history and role models.

Activism

In 1981, 13 young black people died in a suspected arson attack on a birthday party at a house in New Cross, London. There are records about this fire and the ensuing Black People’s Day of Action protest.

Arts

The archive holds records about the Caribbean Artists Movement (1966-1972) set up to prevent the marginalisation of artists and writers. It gave creatives opportunities to meet and share their work.

Publishing

Material held in the archive includes a collection about a series of international book fairs of radical black and third world books between 1982 and 1995.

A visit to the archive

The George Padmore Institute, named after influential pan-Africanist and writer George Padmore, was set up in 1991 by a man called John La Rose. La Rose was an activist, poet and publisher.

His dream was to encourage understanding of the history and experiences of black communities of Caribbean, African and Asian heritage in Britain and Europe.

The collection contains materials about some of the most important and successful movements, events and campaigns organised by black communities in Britain from the 1960s to 2000s. The institute has at least 13,000 items on its database.

The organisation, which is a charity, helps organise black history talks and workshops, taking items to and holding workshops in schools and community settings, as well as publishing books and other materials.

Ledger and I first visited the George Padmore Institute in January 2022. We started off by visiting the New Beacon Bookshop, Britain’s first black publisher and bookshop. Thumbs up to it. It was a great place.

After we had looked round the bookshop, we went upstairs to the institute to meet archivist Sarah Garrod. As you climb the stairs, you can see calendars from the 1980s published by New Beacon Books.

At the time, many families were saying images of black children in the press tended to be negative and associated with bad behaviour. In response to this, New Beacon published calendars showing black children and young people doing ordinary childhood things – playing, reading, having fun – no different from any other child or young person.

Seeing history: Paul Christian is working on easy-read materials for the archive – photo: Sue Ledger

New Beacon Books was set up by John La Rose in 1966. At that time, it was the only independent black publisher and bookseller in the UK.

In the 1960s and 1970s, it was hard to find publications with positive images and stories about black children and families and black history in general.

The bookshop made these available and printed the work of many black writers and campaigners. It was also the venue for cultural and campaigning events.

The George Padmore Institute is above the New Beacon bookshop on the first and second floors.

Garrod showed us material including posters and photographs about the life of John La Rose and examples of other items in the collection too, such as newspaper headlines, posters, placards, letters, magazines and photographs.

It was mind blowing and inspirational for me to learn about this brilliant man. He achieved so much. I really like the sound of him and the way he made things happen and helped people to come together to challenge injustice.

Garrod is a great storyteller and has lots of photos and objects to bring these important black histories to life.

She said: “It’s my job to look after the collection and to work with people who want to find out about and use the materials in it. I spend most of my time working with researchers, including writers and artists. Some want factual information but others like to browse the archives for inspiration.”

An example is artist Steve McQueen, who drew on material in the archives for his Small Axe films. The institute invited author and artist Ken Wilson-Max to be a writer in residence. He researched the archives to produce children’s books.

Better placed for access

I asked Garrod if the archive had worked with people with learning disabilities before.

“I don’t think we have – that’s not by choice but just the way things have turned out. Poor physical access to this building perhaps made us worry about how best to share our materials but there is always a way round this,” she said.

“We would love to be able to do more going forward and now the collection is catalogued we are in a much better position to find and share all accessible items.

“It’s a great time to start and we can work together to find the best materials and places to use in response to interests and requests.”

She added: “We want to make our black history collection available to people with learning disabilities, their families, teachers, staff and supporters.”

Garrod says anyone wanting to visit can make an appointment and staff will enable them to access the collection. This may include making arrangements to visit with a support worker, meeting in a different location or sharing materials online.

So far, Garrod, Ledger and I have been working together to create easy-read materials for two sections of the archive. We plan to share more about this work in a future issue of Community Living.

Connections between our lives today and black history continue to really matter. It is important for people with learning disabilities who are interested in working to stop racism to make links between anti-racism campaigns led by black people in the 1960s and 1970s and those of today.