The use by local authorities of “affordability” as a principle in financial assessment and charging policies is misleading and disingenuous. Appeals processes are wholly a matter of preference in each council. Most local authority officers are ill equipped to bring public law expertise to bear upon challenges to financial assessment outcomes that can have such a stultifying effect on people’s lives or even their willingness to accept services.

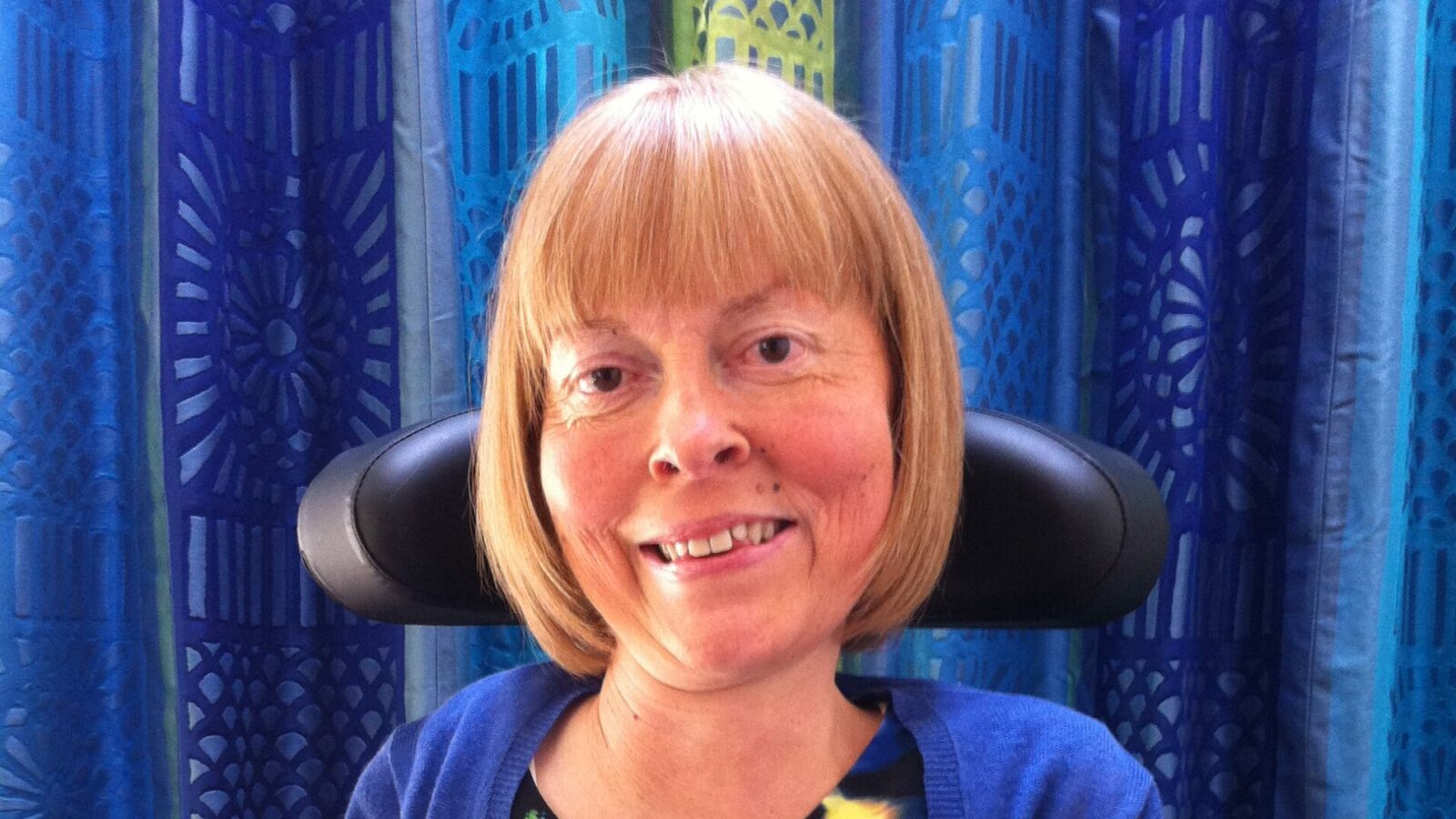

Discrimination against severe disability

In SH v Norfolk Council, the council’s charging policy was found to have discriminated against severely disabled people contrary to article 14 (protection from discrimination) of the Human Rights Act, in taking the whole of a person’s income above the minimum income guarantee into account when calculating charges for social care.

SH, the young woman with Down syndrome pursuing the challenge, was in receipt of both employment support allowance (ESA) in the higher level support group category and personal independence payment (PIP) in the enhanced daily living and enhanced mobility category. She also had a package of care including day services, overnight respite and some community support, via a direct payment under the Care Act. Her lawyers used the idea of discrimination in the context of another human right. They said her status and the way that Norfolk’s charging policy treated her impacted on her life disproportionately, with no objective justification for the differential treatment.

SH’s income from benefits was “property”, which put her interest in that income into the category of an article 1 first protocol right under the European Convention on Human Rights (protection of property). The council argued that “severely disabled” was not a sufficiently specific status to qualify for protection from discrimination under article 14.

However, the judge concluded that this status could be defined precisely in terms of eligibility for ESA support and PIP in the enhanced daily living category. He added that it would be best if, for charging purposes, it was compulsory to compare the result with that for less disabled people to see if there was an unjustified difference in treatment. The discrimination was that the proportion of earnings that she and other severely disabled people with high care needs and significant barriers to work had to pay under the charging policy was greater than the proportion of earnings that people who were disabled but not severely so were required to pay.

Less disabled people will have lower levels of assessable benefit (they will not be paid daily living PIP at the enhanced rate) and may have earnings from employment or self-employment that will be entirely disregarded from their assessments. The council’s position was that because the policy was the same for everyone, there was no difference in treatment. This was quickly dismissed by the judge on the grounds that it is well established that a difference in impact can result in indirect discrimination, despite the same rules being applied.

The council also argued that people subject to the charging policy earning income from employment were not in an analogous position to severely disabled individuals such as SH and were treated differently because they varied in other ways. The judge disagreed. The council argued that, as SH’s higher level of needs would result in higher disability-related expenses (DREs) and these would be disregarded when her charges were assessed, then this flexibility was the equivalent to the disregard of earnings for those able to work.

The judge identified that the definition of DREs under the charging policy was “not at all coterminous with the higher rate of PIP” and, furthermore, that DRE was “harder to prove and claim than the blanket disregard of outside earnings for those able to get them”.

Consequently, he took the view:

“Neither the evidence nor the charging policy suggests to me that the DRE regime reduces to any significant extent, let alone eliminates, what would otherwise be differential treatment.”

The test of objective justification for different treatment involves considerations as to whether, first, the difference is “a proportionate means of achieving a legitimate aim” and, second, the justification for the adverse effect of the rules is “manifestly without reasonable foundation”.

The council’s evidence focused on austerity and demonstrated a conscientious process of consultation and phased introduction of a less favourable charging policy that included measures intended to mitigate the impact on those affected. However, the judge identified that these mitigation strategies were primarily focused on supporting access to employment for affected individuals, a mitigation that was not available to SH.

The council’s consultation and consideration process had not identified or discussed the differential impact between severely disabled individuals unable to access employment and others affected by the charging policy.

Alternative not considered

The council did not evidence ever having considered the alternative approach specifically suggested by the Care Act guidance of setting a maximum percentage of disposable income (over and above the minimum income guarantee) that may be taken into account in charges for everyone or for severely disabled people. The judge highlighted that paragraph 8.47 of the Care Act guidance said councils “should” consider this approach. There has to be a very good reason for departing from guidance, and the exhortation had been entirely overlooked, it seems.

been entirely overlooked, it seems. He was sympathetic to the difficult position facing the council, but quoted from caselaw: “Saving public expenditure can be a legitimate aim but will not of itself provide justification for differential treatment unless there is, in the case in hand, a reasonable relationship of proportionality between the aim sought to be achieved, and the means chosen to pursue it (i.e. the measure under challenge).

“The objectives identified are not sufficiently important to justify discriminating against the most severely disabled as compared with the less severely disabled in order to advance it. The discriminatory impact is not rationally connected to the objective at all.

“A less intrusive measure was suggested by the guidance but was not considered. Balancing the severity of the measure’s effects on the rights of the persons to whom it applies against the importance of the objectives, the discriminatory effect is irrational, unnecessary and wholly out of proportion.”

Implications

Norfolk has already resolved to make an initial amendment to the charging policy for non-residential care for people of working age, setting a minimum income guarantee of £165 per week, and using discretion to disregard the enhanced daily living allowance element of PIP.

The Department of Health and Social Care and the Association of Directors of Adult Social Services are also taking legal advice as to what to do about this case. The obvious aspects of the case that require attention are these:

● If a council does not take the full amount of PIP-enhanced daily living into account as income for assessing adult social care charges, will that be a way of mitigating discrimination?

● Will higher standard levels of DRE for those who get the benefits that put them into the category of severely disabled do the job?

● Can a council focus on a special local buffer for the severely disabled, and take the statutory minimum income guarantee for the rest?

● Can a good decision-making process before changes are made to charging policies ever justify differential treatment – so other councils’ similar policies are presumptively invalid?

● How will a retrospective correction of these policies affect people’s current charges?

Could you claim?

We think that people who have been charged over the past year or two on the basis of a Norfolk-style policy could claim restitution of unlawful charges. We normally require fees for all charging challenges at CASCAIDr but we will be offering a special discounted service to those who do not know whether their council’s policy is like Norfolk’s in the sense required to make it worth taking further advice. We are going to go to the barristers who won the case to see what they think about the implications of the case and publicise the results.

Our enquiries will cover typical charging policy approaches, their discriminatory effect, the precedent effect of the Norfolk case and the most effective approach to further litigation, since the Local Government and Social Care Ombudsman’s office cannot possibly deal with every single charging complaint that will be made.

We are interested in the notion of family members’ contributions to the lifestyles of their loved ones counting as DRE, as used to be the case, because of the concept that the contribution was a loan for necessaries. We suspect that policies that have one standard DRE allowance for all could be discriminatory because, while they allow for evidencing of higher amounts, that is going to be all the harder for those with severe disabilities.

A council’s approach that an activity or purchase is a “lifestyle choice” as opposed to a necessary cost reasonably related to their disability is in our sights. We’ll be looking at the typical rejection of DRE costs without consideration of human rights jurisprudence that refers to the concept that leisure and recreational activities can sometimes be the only way in which a disabled person is able to develop their personality within society, as provided for by the scope of article 8 convention rights. This is because the more seriously disabled the person, the more likely that will be the case.

Our crowdfunding page for the advice described is on Crowdjustice (www.crowdjustice.com/case/disabled-and-done-over), and we hope that the community of people interested in disability will support our campaign to inform and enforce better engagement with these issues.

SH v Norfolk Council: www.bailii.org/RogerBlackwell/Flickrew/cases/EWHC/Admin/2020/3436.html