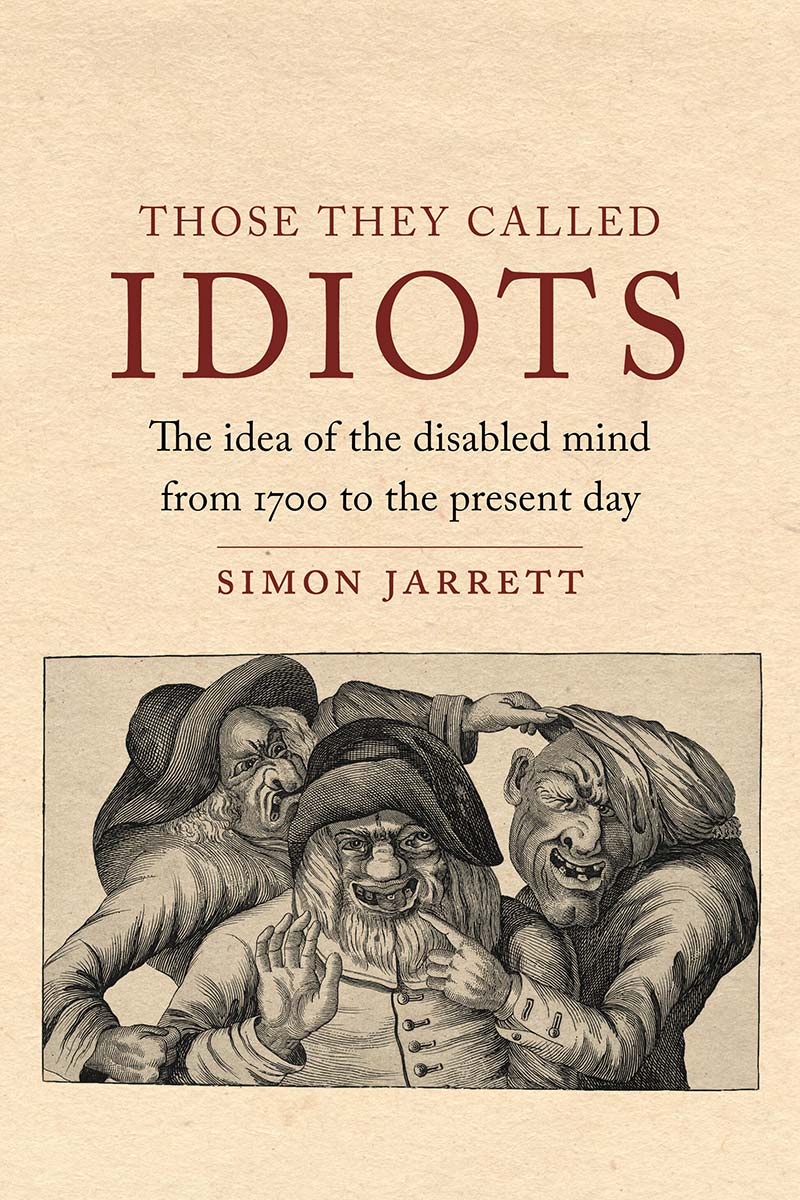

Those they called Idiots: the idea of the disabled mind from 1700 to the present day

Author:

Simon Jarrett

Publisher:

Reaktion Books, 2020

Price:

£25.00 – (352pp)

ISBN:

978-1-78914-301-0

This is a history of those they called idiots, from being fully in the community in the eighteenth century, through 130 years of wilderness and worse, then back into the community at the end of the twentieth century.

In an exceptionally well-written book, Jarrett leads us on a journey of changing fortunes as people moved from a sometimes insulted, laughed at, but tolerated position in 18th century society – supported by families and neighbours, sometimes treated leniently by the courts – through a darkening Enlightenment. The dehumanizing gaze of new philosophy, science and medicine, the toxic anxieties and moralising proclivities of the upper classes, and the radical and reactionary responses to revolution on both sides of the Atlantic, laid the foundations for state-sponsored mass exclusion through institutionalisation, sterilisation, eugenics and, in Nazi Germany, genocide.

Whilst there were still decades of institutionalisation, abuse and neglect after the Second World War, eugenics waned, advocacy by families and support from celebrities and the public on both sides of the Atlantic grew, and positive social theories like those of Wolfensberger and O’Brien took hold. This led to ‘care in the community’, a successful ‘great return’ which Jarrett rightly says we should celebrate. The medical model is dead, long live the social model, although, as Jarrett points out, there is still a ‘ghost of institutions past’ in the form of Assessment and Treatment Units

Books which are academically driven and fuelled by evidence, analysis, and inference from multiple historical sources, as this book surely is, are sometimes impenetrably dense, even dull. Not so with Jarrett, who pieces together the actual and likely lives of idiots from such a rich and compelling panoply of sources and genres, that, despite the sobering nature of the subject, the book is richly colourful and, frequently, a joy to read.

Jarrett exposes and explores dozens of enlightening themes, not least amongst them how colonialism was built and justified on ideas of idiocy and race, and notions of mental incapacity used to dispossess indigenous people of their land, possessions, and self-governance. The vision of white male explorers arriving in their ships with their wondrous scientific instruments on other people’s shores, only to be ignored by those who live there, is grimly comic, though less so when it is clear that their egoistical indignation leads them to confuse indifference with ignorance and feeds their erstwhile stupid ideas about racial idiocy.

Paradoxical gems

Jarrett also reveals paradoxical gems, like the delay in the implementation of the incarcerating Mental Deficiency Act 1913, caused by the First World War, and during which thousands of those deemed mentally deficient, ‘dangerous, unproductive, and parasitical’ actually filled key labour shortages and were an important part of the war effort.

The book’s narrative is compelling and a central thesis, that the journey to inclusion is historically circular, not linear, is richly proven, as is a subtext throughout that the clever, and allegedly intellectually able, are the real idiots of the story. In their bid for ascendancy, allegedly enlightened men of medical science rehashed popular stereotypes and caricatures of idiots and imbeciles from the early 18th century and rebadged it as unique medical knowledge.

Whilst Jarrett finishes his book on a note of optimism, I was left with the distinct impression that our future is being stalked by pernicious ideas from past centuries and we must be on our guard. I worry that the damage done by a hierarchy of intelligence and IQ as a determinant of human value still courses through 21st century veins. Beware those they call clever, for, as Jarrett has proven, they are stupid, and extremely dangerous.