The medical profession’s endemic ethical problems in relation to learning disability have continued to be starkly demonstrated as the coronavirus pandemic continues. As I argued in my last article, these issues are not new – they have been around the profession for more than two centuries and across the NHS since its inception in 1948.

The pandemic, however, has shone a light on these problems and brought them more to public attention than before. As feared, the use of do not resuscitate (DNR) notices against people with learning disabilities has persisted in hospitals throughout the pandemic, as will be confirmed in a forthcoming report from the Care Quality Commission. These orders, formally known as do not attempt cardiopulmonary resuscitation notices, are intended for people who are too frail to benefit from this form of resuscitation. However, they are often imposed on people with learning disabilities simply on the grounds that they have a learning disability, leading to unnecessary and avoidable deaths.

The issue was raised well before coronavirus, and the Department of Health and Social Care has explicitly condemned the blanket imposition of DNR notices against groups of people. Nevertheless, NHS clinicians have continued with the practice throughout the pandemic. Unless a lasting power of attorney for health or an advance directive (also called an advance decision) has been made stating otherwise, any decision to withhold life-sustaining treatment is effectively made on the spot by the lead clinician in charge of a person’s care, once they are deemed to lack mental capacity. The problem is therefore not only an institutional one within the NHS in allowing such practice to occur, but also an individual problem emanating from the clinicians who choose to impose such orders.

A further ethical problem has arisen in the battle to prioritise all people with learning disabilities in the UK Covid vaccination programme. At the time of writing, this programme has been enormously successful and an outstanding example of first-rate public health practice applied to an entire population. It has sought to prioritise those thought to be the most at risk because of age and underlying health conditions. However, people with learning disabilities, despite dying at six times the rate of the rest of the population from Covid (and at 30 times the rate in younger age groups), were not included en masse in the initial prioritisation list. After lobbying from the Down’s Syndrome Association, people with Down syndrome were included from the outset.

After further campaigning, people categorised as having severe or profound disabilities were added to the list. The medical establishment finally caved in on 25 February – three months after the roll-out began – and added the rest of the learning-disabled population to the priority list (around 150,000 people). This happened only after intensive, high-profile lobbying from well-known public figures who have learning-disabled relatives, such as BBC radio DJ Jo Whiley, and campaigning organisations.

It is important to note that, while government ministers are ultimately responsible for the decisions made on their watch, the initial decision to exclude many people with learning disabilities from the top prioritisation categories was made by senior doctors on the Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation (JCVI).

It was not the case in England that Matt Hancock, the health minister, was given a prioritisation list and asked for people with learning disabilities to be removed. The JCVI doctors did not include them on the list in the first place despite the evidence of their own statistics. There is a disturbing parallel between the DNR notices and the initial non-prioritisation in the vaccine programme – in both cases, potential life-saving interventions were withheld from people with learning disabilities.

The irony is that, in the case of DNR notices, treatment is withheld because the learning disability is seen as a vulnerability that makes the person unfit for treatment while, in the case of vaccination, underlying vulnerability is denied.

The shadow of the past

In my previous article, I described how the past casts a long shadow over medical practice in relation to people with learning disabilities today. It was from the time that medical practitioners began to take an interest in learning disability, or idiocy as it was then called in the 19th century, that the exclusion of this previously assimilated group of people began to take place. Medical men – and they were all men – led the asylum system that condemned people to a life behind institutional walls, separated from family and neighbourhoods. There then followed a long line of medically inspired moves to eradicate people with learning disabilities from society altogether. These included the eugenics movement, the Mental Deficiency Act of 1913, campaigns for euthanasia (successful in Nazi Germany), sterilisation and a litany of neglect, abuse and dehumanisation in medically run institutions, which persisted until the end of the 20th century.

Our current medical abuses and exclusions – detention and mistreatment in assessment and treatment units, DNR notices, preventable hospital deaths – are all rooted in this dubious medical heritage. Why does this happen? First, medical practitioners are singularly ill suited to be the arbiters and controllers of the lives of people with learning disabilities. Learning disability is not an illness or a disease, and it cannot be cured or treated. People with learning disabilities are who they are, and no amount of medical intervention will make them into someone different.

This is why, before the 19th century, medical practitioners steered well clear of idiocy. They were paid for curing people and they were not interested in spending time on an incurable, unchanging condition. When medical men were looking for new areas of control and authority in the 19th century, they had to invent a story that “idiots” were a danger to either themselves or others, and that somehow only the medical profession could recognise, control and “treat” these dangers within high-walled asylums. Their choice of language to describe their new patients was revealing – they called them “mental defectives”. If something is defective it is broken. It lacks something. “Defectives” could not be mended; instead, they had to be eased first out of society and then out of existence. Confinement, sterilisation and- eventual institutional death would start to rid society of this group.

The medical profession’s role never was to make people with learning disabilities “better”. It was to remove them from society somehow and to prevent their future existence. The aim was, in short, their extinction. This medical outlook tied in with wider currents of thought. Utilitarian thought dominated 19th century public policy-making and ethics.

It was very much a practical philosophy, applied to everyday life and, by its nature, always loaded heavily against people with learning disabilities, as we shall see.

A seductive, bad idea

We know utilitarianism best by the maxim “the greatest happiness of the greatest number”. Actions are judged by the amount of satisfaction, happiness, improvement or benefits they bring to the greatest number of people possible. Faced with two difficult choices, we choose the one that brings the most benefit or causes the least harm. Like many bad ideas, it is at first sight very seductive and seems to make a lot of sense.

Modern utilitarian thinkers have used what has become known as the “trolley problem” to think though ethical problems. Here, you are standing by a railway line and see a train hurtling towards five people who are tied to the track. You are in a position to change the

points, and can divert the train off on to a spur. However, there is one person tied to the track on the spur, who will die if you switch the points. What do you do? In its basic form for a utilitarian, this dilemma is a no-brainer. You switch the points, even though you are effectively making a decision to kill somebody, because in doing so you are saving five lives while sacrificing one. The numbers tell you this is the right action to take, and you must put aside any squeamishness or moral hesitancy that might cloud your rational judgment.

The trolley problem can be put through all sorts of permutations to tease out the solutions to complex ethical dilemmas. What if the five people were all elderly, with terminal health conditions, while the one person tied to the other track was young and healthy with their whole life ahead of them? Would you switch the trolley then? Or would you not intervene because the one other life was of more utility than or at least equal to the other five put together?

You do not have to jump very far from here to see how utilitarianism is used in current medical ethical thinking. Who gets the ventilator in a Covid ward – the young person more likely to respond or the old person less likely to benefit? Then, what if it is a young person with no health problems against someone of the same age with an underlying health problem? To go back to the trolley problem, what if it is a person without a learning disability tied to the track ahead of you, and a person with a learning disability tied to the spur – do you switch the points? What might the average doctor respond to that?

Utilitarian thinking continues to exert a great influence on medical ethics. The British Medical Association stated in its guidance on ethical issues published shortly after the pandemic began that the aim of the medical profession throughout the crisis would be “delivering the greatest medical benefit to the greatest number of people”. This is a deeply utilitarian statement.

Of course, in medicine there are many terrible dilemmas, and no one would deny that there has to be some sort of framework to assist medical practitioners in such difficult decisions. Most people would probably agree that if you must make a choice between saving an elderly person with a terminal illness and a younger person who is not terminally ill, then you would choose to save the younger person.

Although utilitarianism can appear cold in its rationality, it can be argued that coldness and logic in decision making can be better than raw emotion – do we want a situation where we save people we like and sacrifice people we don’t? disabilities – or “defectives” – as less than full humans who are incapable of true happiness.

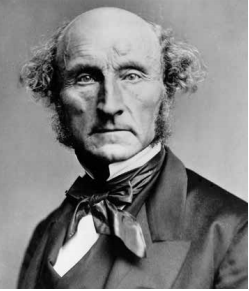

In the utilitarian world, where only happiness (or satisfaction or improvement) of as many people as possible matters, this effectively makes you a non-person. John Stuart Mill, the leading utilitarian of the 19th century, famously argued that “it is better to be Socrates dissatisfied than a fool satisfied”. In other words, “fools” did not experience genuine satisfaction or happiness like intelligent people – just mindless pleasure in the stimulation of their senses.

Mill was an advocate of the asylum for the “idiots” of his time. People who could not be properly be made happy or improved through education did not really belong in society and were a drag on the happiness of the majority.

Persistent prejudice

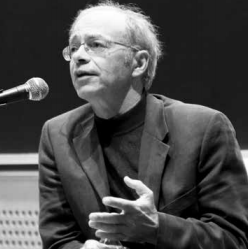

Such thinking persists today, in its most extreme form in the modern utilitarian philosopher Peter Singer. Singer is a leading advocate of animal rights who argues that we should not accord greater privileges to the human species than we accord to non-human species. He calls the practice of human dominance over other species – killing animals for food and clothing, keeping them in farms and zoos – “speciesism”.

To support this idea, he argues that what he calls “retarded infants” have lower abilities and are less capable of happiness than many non-human animals. He calls such infants “human vegetables” and argues that:

“Adult chimpanzees, dogs, pigs, and members of many other species far surpass the brain damaged infant in their ability to relate to others, act independently, be self-aware, and any other capacity that could reasonably be said to give value to life. With the most intensive care possible, some severely retarded infants can never achieve the intelligence level of a dog.” (Animal Liberation, 1975: 18)

Singer calls for the active euthanasia of such infants, and has written extensively throughout his academic career in support of euthanasia against those he calls the “retarded”. Although controversial in the disability world, he remains highly regarded in the world of philosophy and is still considered a guru of the animal liberation movement.

More disturbingly, in a recent article in Prospect magazine, he boasted: “I taught intensive bio-ethics courses for healthcare professionals, including intensive care unit directors and many senior people.” It is difficult to contemplate what might have been taught about people with learning disabilities in such courses. Singer is just one more extremist in a line of intellectuals and distinguished medical practitioners who have waged war over the years against people with learning disabilities (see “The persistent stupidity of intellectuals”, pages 12-13). Nevertheless, he is the very visible crest of a profound wave of thought that dehumanises people with learning disabilities, values them less than other types of human and sees their lives as a tragedy and a burden, best relieved by death.

It is this thinking that sadly, in more subtle forms, stalks the wards of our hospitals and the minds of many who work in medicine. This is not just idle thinking – it results in needless DNR notices, Down syndrome foetuses being aborted at term, people missing out on vaccinations and people being fed through hatches in solitary confinement in assessment and treatment units. We know that, despite all this, there are many good people who work in the healthcare professions – doctors, nurses, psychiatrists and many more – who do not sign up to these assumptions, and who place value on the lives of people with learning disabilities.

It is time for them to come together, to join forces inside and outside their professions, to challenge this dehumanisation and oust it from medicine once and for all. The greatest happiness must belong to us all.