The last year has been quite a year for eugenics.

First there was the news that Andrew Sabinsky, one of Dominic Cummings’ new intake of “weirdos and misfits” to act as government advisers, had claimed that eugenics was about “selecting for good things” and that intelligence is largely inherited”. Then Richard Dawkins, evolutionary biologist and author, popped up on Twitter claiming that since eugenics “works for cows, horses, pigs, dogs and roses”, there was no reason to think it would not “work for humans”.

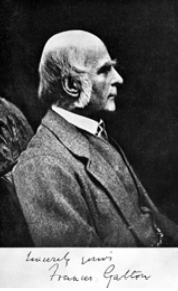

He conceded there might be grounds for rejecting the practice before claiming, absurdly, that “facts ignore ideology”. It was the distinguished English scientist Francis Galton who, fascinated by his half cousin Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species, asked: “Could not the race of men be similarly improved? Could not the undesirables be got rid of and the desirables multiplied?”

In 1883, he coined the term “eugenics” and set out to improve the human race by “better breeding”. His supporters soon linked “undesirables” to a range of social problems and called for government action to improve “biological quality”. In 1907, Galton co-founded the Eugenics Society and, in 1908, Sir James Crichton Brown, in evidence to the Royal Commission on the Care and Control of the Feebleminded, recommended the compulsory sterilisation of the “feeble-minded”, describing them as “social rubbish” who should be “swept up and garnered and utilised as far as possible”.

Darwin’s son Leonard presided over the first eugenics conference in 1912 and lobbied the government to establish squads of scientists, with the power of arrest, who would travel around the country identifying the “unfit” and segregate those so classified in special colonies or have them sterilised. Political supporters included socialist firebrand Will Crooks, who described “mentally defective children” as “absolutely useless”, comparing them to “human vermin” who do “absolutely nothing, except polluting and corrupting everything they touch”.

Meanwhile, Julian Huxley asked plaintively: “What are we going to do? Every defective is an extra body for the nation to feed and clothe but produces little or nothing in return.” A bill for the compulsory sterilisation of certain categories of “mental patient” was proposed, with Labour MP Archibald Church wanting to stop the reproduction of those “who are in every way a burden to their parents, a misery to themselves and in my opinion a menace to the social life of the community”.

Soon, a government committee recommended legislation to ensure the “voluntary” sterilisation of “mentally defective women” – a move welcomed by the Manchester Guardian but, thankfully, never passed into law. Confronted by a “long line of imbeciles”, novelist Virginia Woolf insisted that they should “certainly be killed”. Birth control champions Margaret Sanger and Marie Stopes were both confirmed eugenicists – championing not just contraception but, as Sanger put it, sterilisation for “that grade of population whose progeny is already tainted, or whose inheritance is such that objectionable traits may be transmitted to offspring”.

Some of British socialism’s most celebrated names agreed, including the founders of the Fabian Society, Sidney and Beatrice Webb, along with Harold Laski, later Labour Party chair, who predicted that the time was coming “when society will look upon the production of a weakling as a crime against itself”

These views were echoed by economist John Maynard Keynes and, in 1931, the left-wing New Statesman magazine asserted that “the legitimate claims of eugenics are not inherently incompatible with the outlook of the collectivist movement”.

Lethal suggestion

Philosopher Bertrand Russell proposed colour-coded “procreation tickets” to prevent the elite’s gene pool from being diluted by inferior stock, while George Bernard Shaw insisted that “the only fundamental and possible socialism is the socialisation of the selective breeding of man”, suggesting that defectives could be dealt with in a “lethal chamber”.

Using the same haunting phrase, author writer DH Lawrence declared: “If I had my way, I would build a lethal chamber as big as the Crystal Palace, with a military band playing softly, and a cinematograph working brightly; then I’d go out into the back streets and the main streets and bring them all in, the sick, the halt and the maimed: I would lead them gently, and they would smile me a weary thanks; and the brass band would softly bubble out the Hallelujah Chorus.” He could have been describing a suburban English Treblinka.

It took Nazi Germany and the murder of 250,000 people deemed to be living “lives unworthy of life” to put these fantasies into action. But the unhappy truth is that even after the Second World War, the eugenics agenda in Britain was still current.

Nazi ideas survive the war

On the day in 1943 when his famous report was being debated, William Beveridge, the creator of the welfare state, slipped out of the gallery of the House of Commons to reassure a meeting of the Eugenics Society of his continued support.

eugenics would work in humans as it did in

“cows, horses, pigs, dogs and roses”

AF Tredgold concluded that: “Many of the defectives are utterly helpless, repulsive in appearance and revolting in their manners. Their existence is a perpetual source of sorrow and unhappiness to their parents. In my opinion, it would be an economical and humane procedure were their very existence to be painlessly terminated.

existence to be painlessly terminated.” The Nazis had been defeated but, for a moment, it seemed possible that one of their most repulsive policies might survive. Such views are thankfully rarer today, but a double standard is still in evidence in the way that abusive language is used, with racist and sexist terms being strictly taboo but their learning disabled equivalents – “idiot”, “cretin”, “imbecile” and “retarded” – are all too common, even in supposedly progressive circles.

Representations in drama and art are infrequent and often misguided, emphasising individual tragedy, not the broader social experience. And scholarship is hardly exempt, with moral philosopher Peter Singer dismissing our protection of the profoundly disabled on the grounds of “speciesism” – declaring that their intellectual capacity is less than that of many animals.

One of his followers Jeffrie G Murphy even wrote an article in 1984 entitled Do the Mentally Retarded Have a Right to be Eaten? He insisted this was a philosophical exploration, intended to “raise the issue of rights for the retarded in its hardest context”, adding sternly that “too much well-meaning sentimentality is allowed to pass for thought in the discussion of the retarded, and I want to shock my way through this”.

Dawkins, in response to an enquiry from a woman about what to do if she discovered she was pregnant with a foetus with Down syndrome, replied “abort it and try again. It would be immoral to bring it into the world if you have the choice”.

He denied that he was a “eugenicist” but it is hard to understand what he meant by the word “immoral” in such a context. |His comments that eugenics would work neglect the fact that eugenics has been tried and it failed abysmally: despite the Nazi programme of murder and sterilisation, Germany’s population of disabled people is entirely in line with other countries. It takes an intellectual to come up with such poisonous guff.

Protecting the rights and opportunities of the learning disabled is hard enough; what’s striking is the way that so many otherwise clever people fail to get it.

This article was published in Byline Times in 2020 and is reproduced with permission

Stephen Unwin is a theatre and opera director, founder of the English Touring Theatre and the Rose Theatre, Kingston, author of the play All our Children, which is about the Nazi genocide of disabled people, and father of Joey, a young man with severe learning disabilities