There were two central aims of this research project. Begun in 2015 when the efforts of all of those who contributed, in whatever way, to the war effort of England and the Allies during World War One (WWI) were being remembered and celebrated, this inclusive research project explored whether and how people with learning disabilities also contributed. The research teams wanted to commemorate this history as a legitimate part of the efforts of others in society, to bring a hidden part of learning disability history into the light.

The second, and equally as important, aim of the project, was to have people considered to have learning disabilities today, research and record this themselves. The project documents the fact that people with learning disabilities have always played a part in shaping the society in which we all live, whether that be through fighting in  wars alongside their comrades, or by building and extending our knowledge of what happened in history. In this sense the project is a dual commemoration, of the skills, abilities and inputs of people with learning disabilities in history and in the here and now.

wars alongside their comrades, or by building and extending our knowledge of what happened in history. In this sense the project is a dual commemoration, of the skills, abilities and inputs of people with learning disabilities in history and in the here and now.

Readers will know, the year before war began, 1913, is a date of specific significance in the history of learning disabilities since that year marks the passing of the Mental Deficiency Act. The new act established the Board of Control for Lunacy and Mental Deficiency, giving this body sweeping powers to oversee the ‘care and management’ of four categories of ‘mentally deficient’ people then known as idiots, imbeciles, feeble-minded and moral imbeciles.

Tens of thousands of people deemed mentally deficient were incarcerated, on grounds that they could not care for themselves nor learn to care for themselves. This is the backdrop to our investigation of mentally deficient people who came to be recruited into the army between 1914 and 1918.

As this research project has conclusively shown, people with learning disabilities did contribute to the war effort, in a wide variety of ways. This fact asks searching questions of the adequacy of the categories developed by the 1913 Act, categories which shaped the lives of hundreds of thousands of people with learning disabilities throughout most of the 20th century. Our research shines a searchlight on the nature of the tests which claimed to be diagnosing people with learning disabilities, and on the underlying belief systems and claimed knowledge of the medical and political leaders overseeing the ‘management’ of people with learning disabilities.

Inclusive Research

Inclusive research teams, drawn from the membership of My Life My Choice (MLMC), an Oxford-based learning disability organisation, shaped the project from the very beginning, both in a range of roles as frontline researchers and ‘back-room’ advisors. The initial research directions were agreed upon collectively and shared with advisory committees made up of MLMC members. All data gathering was co-researched and often and throughout how we developed our findings into new research directions was decided on by MLMC members.

The team used a range of research methods including interviews, field trips in the UK and abroad and archival research. Each element was set up with an introductory meeting to discuss methods, with research groups free to contribute, criticise and guide in various ways. This stage was followed by the research activity itself and final, reflecti ve group meetings to consider key learning, mistakes we’d made and discussion of future activities.

ve group meetings to consider key learning, mistakes we’d made and discussion of future activities.

These stages did not always involve all of the research group together but all of the team worked hard throughout both the first and second phase of the research to make sure experiences and learning was shared as widely as possible within and beyond MLMC. For example, at the end of the first phase of research a number of dissemination events were held, presented by MLMC members. This included a presentation in south London to a dance group, Magpie Dance, and their patrons and supporters.

This event resulted in further collaboration between the two groups out of which Magpie Dance produced a dance work commemorating people with learning disabilities’ contributions during WWI exhibited in various venues including the Royal Opera House.

From day one, finding appropriate data was a huge challenge. With war beginning in 1914, one year after the 1913 Mental Deficiency Act, knowledge of a specific set of disabilities to do with intelligence was very sparse. The term ‘mental deficiency’ itself is likely to have been known to only a small number of army medics.

It is unlikely that any of the army personnel responsible for recruiting, training, assigning and otherwise managing soldiers will have been familiar even with the term, let alone the set of symptoms perceived to indicate intellectual problems. The tests for mental deficiency were themselves disputed.

There was no consistent test for intelligence levels in the British army recruiting system. As Steven Gelb shows, in the US, where a contested system was used in an experimental way, the results were disastrous, suggesting an average mental age of US soldiers in the entire US army of just 13. Fully a quarter of US soldiers were shown to have a mental age as low as 11 using these tests. All of these problems and more made data gathering challenging, but also hugely enjoyable. We were detectives searching for clues under every mattrass.

Profound effects

A key focus for the first phase of the project was for the team to visit, become familiar wit h and develop confidence in dealing with historical archives and historical artefacts. This task was strongly supported from the beginning by the impressive nature of the two archives we first visited – The Oxfordshire History Archive in Cowley, and the Soldiers of Oxford Museum in Woodstock – and by the tremendously helpful response and guidance from the archive staff.

This is one of the major finding of the whole project, in fact. The response from staff in all of the archives and facilities we visited, through both phases of the research, was at all times to approach this as an important research project and to deal with the research teams in professional, accommodating but serious ways. At no time did the teams report feeling patronised or talked down to in any way, reinforcing their belief in themselves and in the value of the project.

A trip to the battlefields in France and Belgium in the winter of early 2017 was, perhaps, the crowning glory of this first phase. It is not possible to capture the profound effect this incredibly moving trip had on the MLMC research team. Suffice to say, those that went experienced the history of WWI at deeper levels than any number of classroom- or archive-based sessions possibly could. By the end of that trip, wonderfully facilitated by local historians in the region who gave privileged access to many artefacts and important documents to the team, we firmly believed that people with learning disabilities had fought in the war. We were confident it was a matter of persisting in order to find the evidence so that the lists of the dead, the destruction of human life the French and Belgium commemorations express, included the history of people with learning disabilities.

Building on leads we had established in the first phase of this project, early on in the second phase we began to find the evidence we’d been looking for. These we got, primarily, from two sources.

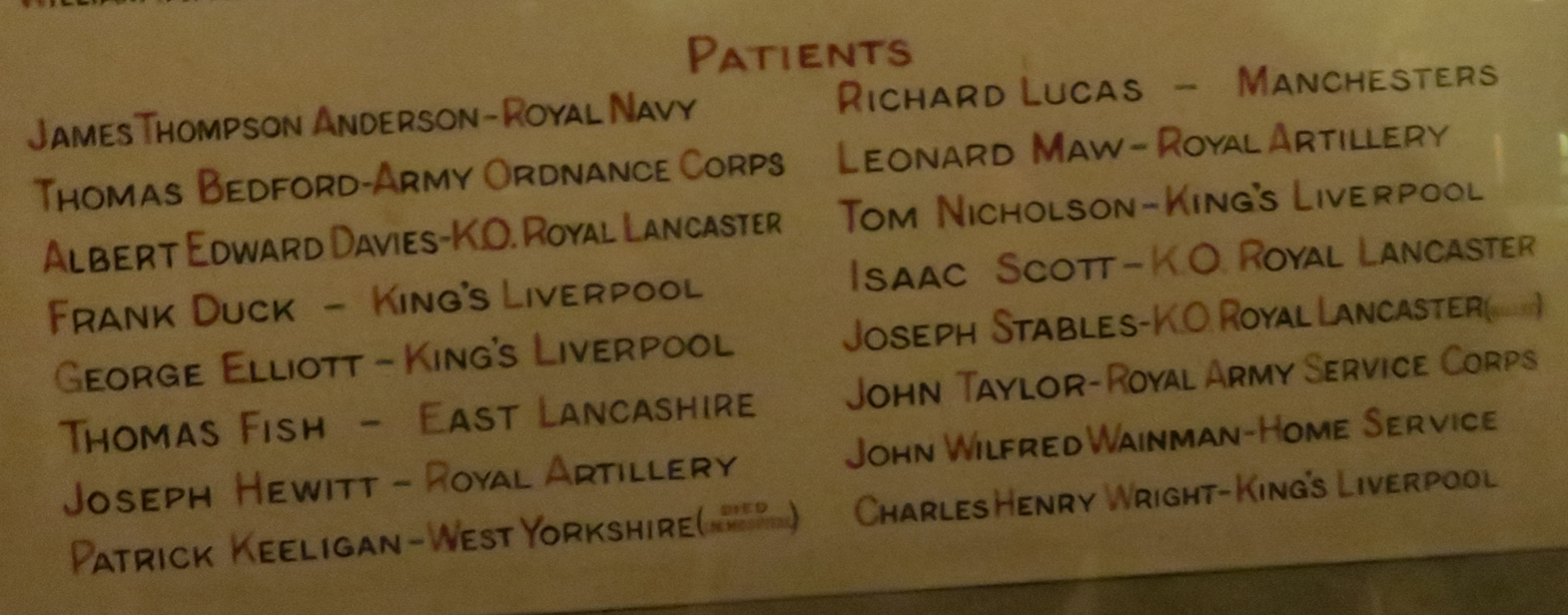

One resulted from a field trip to Lancaster in the north of England where we visited the Royal Albert Hospital, one of the oldest long-stay institutions for people with learning disabilities in the UK, now repurposed as a residential school. For many years, a Roll of Honour was displayed in the entrance hall to the main building listing sixteen former residents who enlisted in Lancaster’s Kings Own Regiment and fought in France.

The plaque has now been moved to the Regimental museum in Lancaster itself. The research team are now in the process of attempting to fill in some of the missing details for this list of names, using MyHeritage. Com and other online heritage software. It’s a painstaking, detailed and on-going task.

A second major data source were the National Archives at Kew Gardens, London. Earlier on in the project we discovered soldiers suffering from injuries related to mental wellbeing had been sent from various field hospitals in France back to the Royal Victoria Hospital in Netley, Southampton, and specifically to ‘D Block’ there. Having been able to focus our efforts to this one source we began to uncover a growing number of individuals we could identify as soldiers regarded by army medics as people with learning disabilities.

This list so far includes the likes of Arthur Pew, 19th Kings Royal Rifles Corps, described as having come into the army from an asylum where he ‘was considered to be a mental deficient’; Charles Adams, 25, 9th Rifle Brigade, described as ‘This patient is obviously feeble-minded’; Robert Douglas, 19, Durham Light Infantry, ‘Imbecility. He is dull and listless’; John Shaw, 22, Royal Warwick Regiment, ‘Unintelligent. Dull in understanding’; Robert Shackleton, 20, Royal North Lancs. ‘Dull, confused, incoherent, rambling’; Samuel Moore, 22, ‘Stupid looking’.

There are around 30 other examples of similarly diagnosed individuals. As this short excerpt from the fuller list shows and as we discussed in the Methodology section above, the terms and language used to describe soldiers presenting with a range of intellectual conditions is itself wide-ranging and inconsistent. Whilst terms like ‘imbecility’ and ‘feeble-minded’ adhere more closely to the medical terms then in use, terms like ‘dull’ and ‘stupid-looking’ are ones which were also routinely used throughout the years following WWI to describe a learning disability cohort.

Many questions

The discovery that people with learning disabilities served at the front during WWI Raises many, many questions, lots to do with recruitment procedures and lots more to do with the nature of learning disability itself. Research has recognised that recruitment approaches during the war were often lax, with a documented history of under-age, in effect ‘boy’ soldiers being taken on and sent to fight. Research suggests their number increased and procedures grew increasingly lax as the war continued and the need for infantrymen increased.

It is likely this context, and the total absence of intelligence testing in the recruitment process, supported access to local regiments, even, as the records from Lancaster show, when recruits with a ‘mental deficiency’ were recruited directly from institutions. Learning disabled soldiers may also suggest that a distinct, known and knowable ‘mentally deficient’ identity had not developed by wartime. Recruiting and medical officers simply didn’t know what they were supposed to be looking for and were supposed to expect from someone deemed mentally deficient.

I would also argue that this research shows that identities are not fixed, that there is not a stable and unchanging mentally deficient (or learning disabled) identity at all, but that identities are context driven. In a workhouse or long-stay institution someone regarded as mentally deficient might be expected to adopt certain behaviours, recognised by doctors as consistent with cognitive deficiency in that specific closed and institutional space.

But in the context of an army corps, on the front line in the trenches such consistent identity-driven behaviour was simply not tenable. In changed circumstances people – all people – change. In survival situations people change in order to survive. Of the sixteen Royal Albert residents who enlisted, fifteen returned, having learnt how to survive in the hell that was WWI.

One of the records we found at Kew was of a soldier released from the army on the basis of what one medical officer regarded as a mental deficiency symptom after having attained the rank of corporal in a rifle corps. He had learnt to fire a deadly weapon and gave orders to subordinates from a position of responsibility. In these circumstances, what on earth does mental deficiency, or learning disability mean?

It has been recognised, quite rightly and still not to a sufficient degree, that women played an essential role in both military and industrial capacities during war. Also, it is acknowledged, again on the fringes of research but significantly, that Chinese and Indian soldiers played important combat and support roles during WWI. To this point, the contribution of people with learning disabilities during war had not been acknowledged at all.

Still, their role as part of the munitions and other non-military workforce has not been unearthed, a key missing part of our research so far which it remains important to address. Our research does, however, conclusively show that during WWI numbers of people with learning disabilities signed up, fought and suffered injury, alongside others of their class, in the fields of France in the 1914-18 war.

Photo credits:

Italian Army in trench: Italian Army – https://www.corriere.it/cultura/14_ottobre_07/tanti-eroi-senza-fanfare-prova-trincee-4e91135a-4e06-11e4-b38c-5070a4632162.shtml

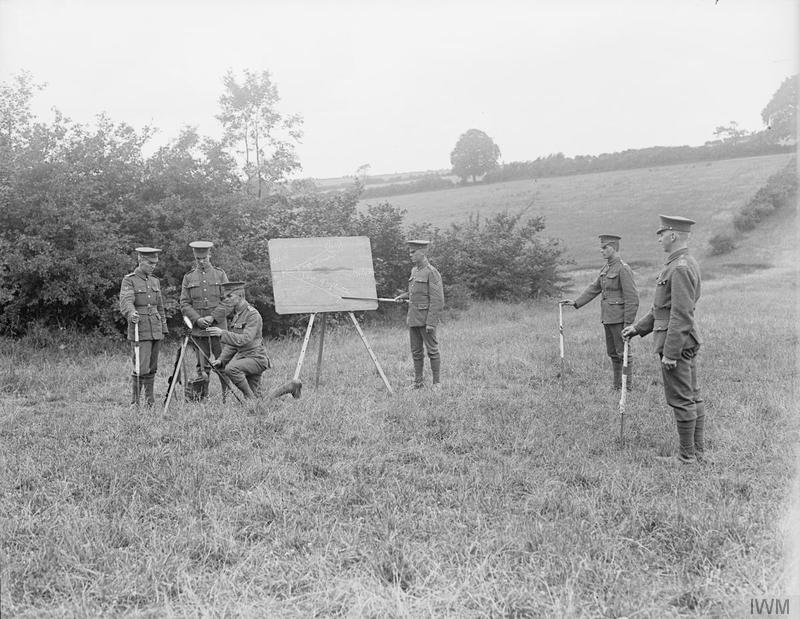

Ministry of Information First World War Miscellaneous Collection Q33704.jpg

Irish Guards: Lieutenant Ernest Brooks – https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205235907