Learning Disability England is “bringing people and organisations together to create a movement for change where people with learning disabilities, families, friends and paid supporters come together on an equal basis”, according to its website.

It also wants to make sure that “what is important to people with learning disabilities is heard and understood”.

Fair enough, you might think. We need a movement to speak up about the changes that are needed so people with learning disabilities can have better lives.

But think a little more and it becomes clear that the task is not so straightforward. People with learning disabilities are a disparate group and, once you add in family members and friends and allies, that’s a lot of potentially different views.

You start to wonder: how does Learning Disability England decide what changes to push for? Well, recently I met with three people from LDE to find out more.

Jodie Williams is a self-advocate and trustee of LDE. As a trustee with learning disabilities, she is pleased to also co-chair the trustees, along with Sarah Maguire, chief executive of Choice Support.

Williams says: “I really, really enjoy the opportunity because I feel like people with a disability and autism don’t get chances like this, and I have worked my way up from being an advocate to being director of different groups.”

She tells me she has a permanent position with the NHS as a learning disability autism network manager: “It feels good to say I am a trustee or a director.”

Jordan Smith co-chairs the representative body at LDE. The rep body, as it is usually called, is made up of 12 people. Four are self-advocates like Smith, four are family members or friends, and four are paid supporters. These three groups are the three voices that decide LDE’s position.

Sometimes, we will put a statement out we know that only maybe 80% of our members agree with but we have to represent the majority

Smith also has a role as advocacy lead at Dimensions but says: “I am not a director of anything. The only thing I direct is my life, which is very important.” I soon learn that Smith can be relied on to keep the smiles coming.

Sam Clark has been chief executive of LDE since 2018. “I think a big part of my job is to support and facilitate other people leading rather than being a traditional chief exec who leads everything,” she says.

“So actually LDE works really hard to try to do things differently – and I really believe in that. Sometimes that means things are a bit more complicated for us or we wrap ourselves in knots but I think we are learning about how to do that.”

So, let’s hear more about the knot-wrapping.

Well, the first thing all three want to make clear is that the rep body is not just a participation group – it is part of LDE’s legal structure.

As well as deciding where LDE stands on issues, it chooses the trustees. Rep body members are voted in by the wider LDE membership.

Smith says the process is like standing to be an MP in parliament: “We do manifestos and say why we want to be on the rep body and really bring our skills and qualities to that. We get voted in by our members and then we get to sit on the rep body for a specific amount of time.

“Why LDE is different is that it is member led. We listen to our members and that is what shapes our work.”

Clark says: “The rep body is the most important bit. And that’s sometimes a bit tricky to manage because the trustees also are an equally but different important bit because they have the legal responsibility.”

Smith agrees: “None of this is tokenistic. We are not here because we have to have people with learning disabilities or autism. If I wanted tokens, I’d go to the funfair!”

Both groups are supported by the small central team. At the time of writing, elections for the rep body were taking place.

After that there are plans to increase the number of trustees. They had planned to do that in 2020 “but we did Covid instead”, says Clark.

They are also very aware that they need to improve the diversity on the trustee board. Currently, the trustees are made up of what Clark calls a group of “really brilliant women. But, you know, they are all white women.”

Williams explains that all trustees are on the main committee, with some also on subcommittees dealing with finance or staffing.

“We help manage the staff, the money, anything that Sam needs help with. She would come to me and Sarah and we would have a discussion.”

It sounds pretty supportive and Clark confirms that she has not been left to deal with difficult issues on her own.

Disagreements and communication

I ask Smith what happens if some of the groups on the rep body disagree on an issue. He says it is essential to consult the wider membership group and describes the Zoom calls, catch-ups and conversations that went on during the pandemic.

“We know that everyone communicates differently. That might be through a discussion, it might be through easy read. It might be through surveys. We have a newsletter that goes out every week where we tell members: ‘This is what you’ve said – this is what we’ve done.”

“You have to gather – what’s the word? – consensus, for one position, which can be quite difficult. And, sometimes, we will put a statement out there that we know that only maybe 80% of our members agree with but we have to go with the 80% because we have to represent the majority.”

Discussion and persuasion on the rep body is an important part of the process. Clark says it is not uncommon for a member of the group to come up with an angle that others have not considered.

“And everybody will say: ‘Oh I hadn’t thought about that. Well, now I have thought about it, I don’t think the same.’”

Are the three member voices each given equal weight? Clark says, yes, they are equal, but Rob Greig (a member of the rep body) introduced the idea that the self-advocates should be the first among equals.

So the self-advocates are always first to give their opinion on an issue, followed by family and friends and paid supporters.

Clark says: “One of the things we’ve been clear on is that we try and work out what we can all agree on. And, if we can’t agree, then it might be that we don’t do something about it at that point, because LDE exists to take action on the things that those three member voices agree on.”

Jodie Williams: ”A lot of my life, people have not given me the chance to do a lot of things. They say: ‘Oh you can’t do this’ ”

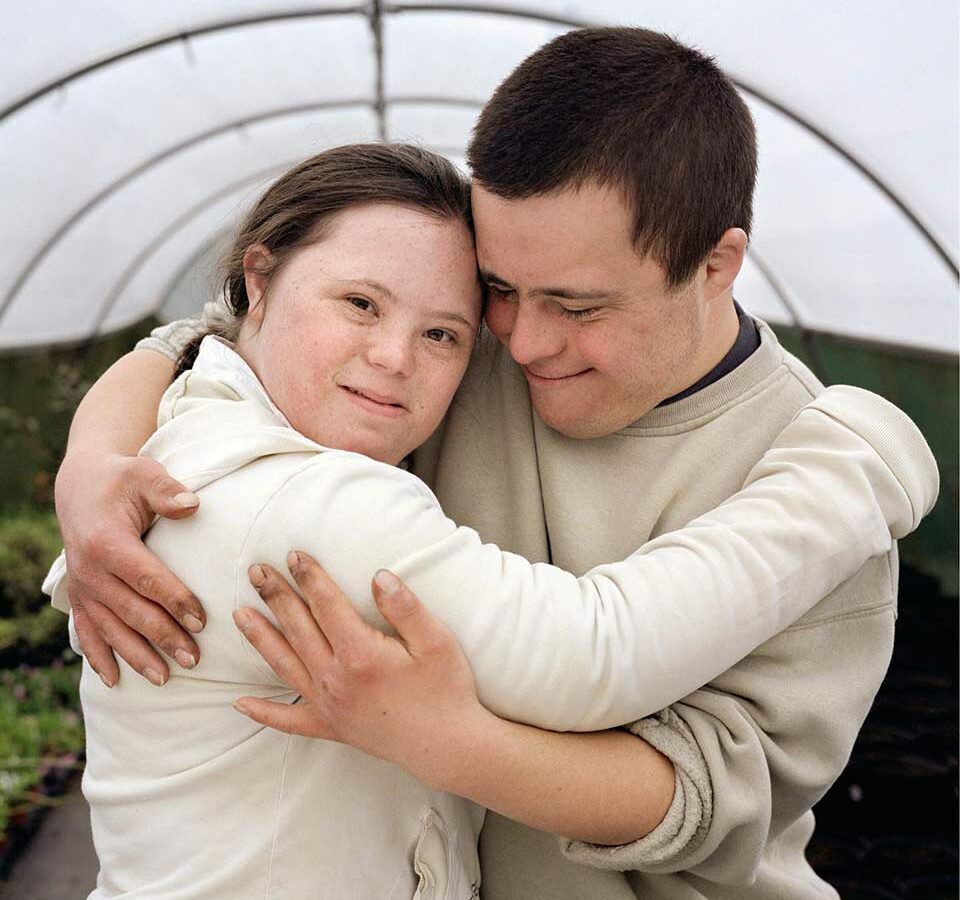

Strong view on Down syndrome law

A fairly recent example was the Down Syndrome Bill. LDE took a firm stance, saying: “We will only support the bill if it includes all people with a learning disability.”

There was a fairly strong consensus on taking this position of more than 80%. Of course, some people disagreed and supported the Down Syndrome Bill as it stood.

Even so, there was still an underlying agreement and mutual respect, says Clark: “So, actually, the members who supported the bill still agreed that we want something for everybody to have a good life.”

Agreeing to disagree

Clark says this is the pay-off from a lot of groundwork: “I think the biggest thing that has changed over the last few years is the shared understanding. I think we have worked really hard to build and to trust each other. To be able to say – I don’t agree with this, I don’t agree with that, or deal with problems.”

It sounds almost too good to be true. Have they found nothing difficult? I wonder.

“When do we struggle?” Clark asks, and Williams replies: “I think when we struggle is if there are any staff or financial problems, or if people are not being very nice.”

They can all recall when something like that happened. Smith adds that because a lot of what LDE does is in the public eye, they are always at risk of “trial by social media”.

He adds that limited staffing capacity sometimes means that LDE cannot do all the things it would ideally want to do. But, overall, it is clear that involvement with LDE is a positive experience for rep body members and trustees.

“The rep body are all volunteers,” Smith says. “We all volunteer our time because we want to help people, because we all have experience of having a learning disability or autism, or experience of being a family carer, or experience of working in social care.

“I want my friends who have got a learning disability and who have got autism to live as long and as healthy as my brothers who don’t. Why do we have to continue to fight on these issues?”

Williams agrees: “I want more people to see what people with disabilities can do rather than what we can’t do. A lot of my life, people have not given me the chance to do a lot of things. They say: ‘Oh you can’t do this.’

”But I have just got my own place with my own mortgage. I have got a partner. I go out like everybody else. I go to pubs. I go to concerts. I do everything like everybody else. Why can’t I have a life like that?”

And who could argue with that?

Not me.