Special needs education separates children from peers, leads to limited adult lives and will persist as long as those with cognitive impairment are seen as not fully human, argues Chris Goodey.

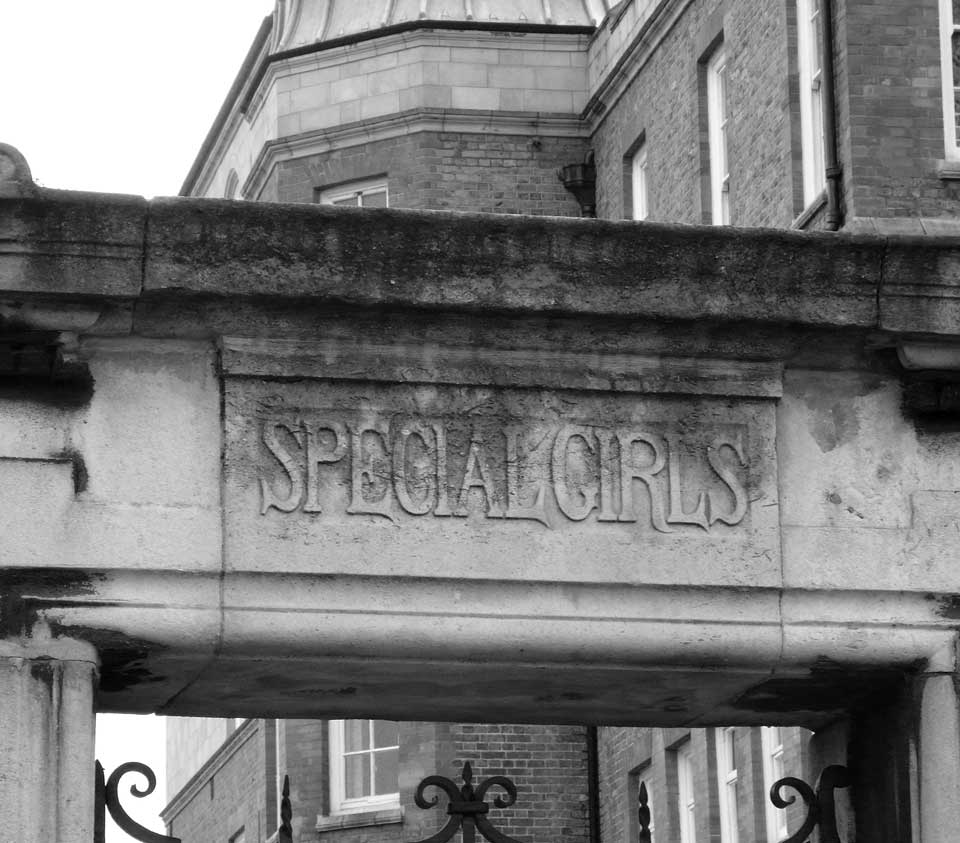

Special and set apart: many disability charities and adult advocates do not call for inclusive education.

Photo Christy Lawrance

One hundred and twenty thousand people with learning disabilities in this country are still being placed in segregated institutions. A huge overestimate?

Not if children are people. Not if the institutions concerned are schools. And not if the word for segregated is “special”.

The Valuing People policy of inclusion and ordinary lives, now (in theory) acceptable for the adult 70% of people, is still being denied to the younger remainder who are in special schools. And segregated childhoods lead to restricted adult lives.

The Children and Families Act 2014 makes a presumption in favour of inclusive education, saying it is a matter of parental choice. These are weasel words. Are you in any position to have your choice accepted?

The government has tendered for new segregated schools. Most ordinary schools are resistant to taking children with learning disabilities. Most local authorities are indifferent. An equality tribunal will usually support you for an ordinary school place – if you get that far. Mostly, you won’t.

The top rank of civil servants and politicians is awash with people who, being privately educated themselves, went to segregated schools that denied them access to normal role models. In my experience of lobbying such people, they are laughing inside at the absurdity of the idea of these children being in mainstream classes.

If this is so, it is out of sheer ignorance. In the occasional school or classroom where it does happen, it happens easily.

“Surely it needs planning.” So does cooking an egg. “Surely there must be some children who it won’t suit.” Then the system is not inclusive. “Surely such a big overall change needs to be phased in.” Then it won’t happen.

Teachers given a lead have been fine with year 11 classes where young people who are going on to become doctors or psychologists are educated alongside someone with severe learning disabilities.

At the root here is often just the grit of an individual parent, the understanding of an occasional headteacher or affirmative action from an isolated local authority.

Your chance of being in a segregated school if you live in Torbay, Devon, is an astonishing 11 times more than if you live in the borough of Newham in east London. If one can do it, they all can.

Authorities are funded across the board for special needs and can allocate this money how they like. They are also legally in control of special needs provision in their local free schools and academies.

So: no excuses. The problem is at the top: lack of leadership. Doing it is not hard. Wanting it is.

Where might pressure come from? Pressure groups about inclusive education deal with all disabilities and other inequalities generally. This is understandable but a general learning disability policy is of no help since, in practice, people with learning disabilities are last in the queue.

Why is this? Because the prevailing view is that cognitive ability is what makes us human so, unconsciously, their full humanity is not accepted – even, sometimes, by other disability activists and advocates.

When the Equality and Human Rights Commission endorsed the inclusive education clause in the United Nations’ Declaration on the Rights of the Disabled Person, it added a rider: for children “with very severe learning disabilities this is neither possible nor appropriate”. Yet the United Nations defines “rights” as inherent in being human. Put two and two together.

The big organisations – Mencap, the Down’s Syndrome Association, the Council for Disabled Children, IPSEA (Independent Provider of Special Education Advice) – bottle out, afraid of antagonising parents already in the system.

The fact is, however, that most parents do not favour segregated schools. At best, such schools may be sort of all right. At worst, they are neglectful or even abusive.

It is no fault of parents that they are unaware of the possibilities.

Hostility to parents

Parents who get as far as the door of an ordinary school will meet hostile school managers. Who wants that when from your child’s birth you have been sensitised to the negative attitudes of professionals, such as the paediatrician who gave you the diagnosis? If parents were offered a local school where inclusion worked, how many would refuse it?

Even adult advocates seem reluctant to engage with inclusive education. Why? Because we are all reluctant to see children as complete human beings – all children, not just those with disabilities.

Psychologists have foisted the idea of “developmental stages” on us. Young children who have not yet reached them and adults who never will are seen as equivalent. Development is not the only way of describing human beings. It is not a science. Our ancestors got by without the idea. We will get nowhere until we recognise that children – children in general – are people.

A new learning disability policy is needed. But it must run from 0-99. Otherwise, there is no point. “Ordinary lives” means ordinary schools.

Chris Goodey has a daughter with severe learning disabilities and writes about the history of ableist attitudes. twitter: @cfgoodey