Creative responses to finding the learning disabled person’s voice within and through research practices have been the focus of recent articles in the British Journal of Learning Disabilities. All articles are open access.

A life in 19th century Milan

Barden O, Walden SJ, Bird, N, Cairns S, Currie R, Evans L, Jackson S, Oldnall E, Oldnall S, Price D, Robinson T, Tahir A, Wright C, Wright C. Antonia’s story: bringing the past into the future. 17 February 2022. https://doi.org/10.1111/bld.12447

Inclusive practice within academic research is expertly presented in this fascinating participatory research paper presented by academics, learning disabled people and their advocates.

Connecting stories from the history of disability to the lived experience of learning disabled people today, the research focuses on the life of a young woman named Antonia Grandoni, who lived in Milan from 1830 to 1872, mostly within an institution as she had been labelled an “idiot”.

Using Grandoni’s story as a reference to how learning-disabled people were treated and experienced life, this project aligned her experiences with people with learning disabilities today, thereby “bringing the past into the future” through the voices of those alive now.

This research leads the way in making sure learning disabled people are key to writing the history that shapes their experiences.

It uses a methodology that considers accessibility at every stage, enabling research to be led not only by “doctors and other people in the medical professions, like psychologists. This means that people with learning disabilities have been excluded from learning disability history research.”

Addressing this omission, this paper presents a team approach where learning disabled people are the researchers.

One team was led by The Brain Charity in Liverpool and the other by the Teaching and Research Advisory Committee at the University of South Wales.

Through information gleaned from the digital archives, the two teams revisited Grandoni’s life story and creatively “rehumanised” her, “with participants recognising and appreciating Antonia as a person, as a woman, as someone who could love and should be loved”.

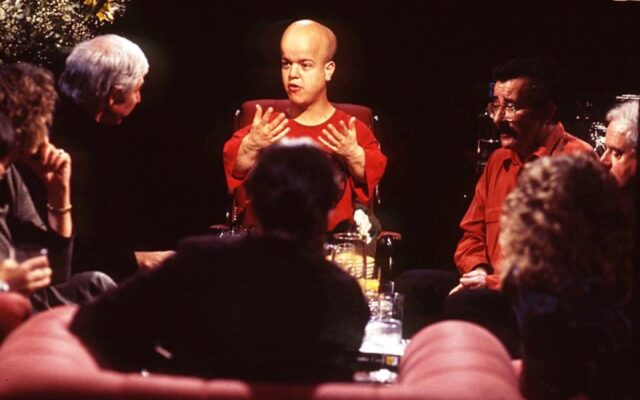

Through group discussions and graphic illustrations, Grandoni’s experience of disability was recorded, reflected and embodied through visuals and eventually the creation of a website to share her story and its impact.

This project reminds us that accessibility is possible and necessary in all stages of understanding the history of disability and that creative mediums aid collaborative thinking.

More about this project and images can be found at www.thebraincharity.org.uk/antonia.

Making research inclusive through a staged, questioning approach

Vlot‐van Anrooij K, Frankena TK, van der Cruijsen A, Jansen H, Naaldenberg J, Bevelander KE. Shared decision making in inclusive research: reflections from an inclusive research team. 7 February 2022. https://doi.org/10.1111/bld.12450

Inviting learning disabled people to become co-researchers is central to this study that invites the reader to follow the team in making research practices inclusive.

Using the method of shared decision-making, the team worked together to make the research process accessible at every stage – design, data gathering

and analysis.

Focusing on “healthy settings for people with intellectual disabilities”, the team worked on a three-year collaboration which required a staged approach throughout.

Finding ways to ensure the co-researchers were involved required the team to continuously reflect and break down the process of the research task.

This challenged the research team’s approach to scientific knowledge and methods which in turn enriched the data gathered, allowing for meaningful participation by those with intellectual disabilities.

In answering the various research sub-questions, the “team deemed the following as helpful: asking one another questions, explaining, discussing the scientific and the experiential knowledge together in easily understood language and using visual supports”.

These strategies were part of how the team engaged with the research where every team member was equally valued and had a role to play.

Co-researchers’ involvement is intertwined with power distribution in decision-making and it is important to find a balance in the team

Adjustments were required and timelines amended as the process needed more thought to make sure participation by the co-researchers was possible at every stage. Simplifying language and using easy-read approaches were especially prevalent as strategies.

The four studies conducted over the three-year collaboration highlighted that “co-researchers’ involvement is intertwined with power distribution in decision-making and that it is important to find a balance in the inclusive research team to make shared decisions”.

This study provides evidence that inclusive research is possible and that people with intellectual disabilities have a role to play, not only because of their lived experience but also as active members of a research team.

This project evidences the stages of how this was made possible and the shared decision-making process that supported inclusive research practice.

Insight into the value of creating and sharing life stories

Ledger S, McCormack N, Walmsley J, Tilley E, Davies I. “Everyone has a story to tell”: a review of life stories in learning disability research and practice. 9 July 2021. https://doi.org/10.1111/bld.12388

Influenced by the telling of his own life story, the co-author of this paper, Ian Davies, is directly quoted throughout, sharing greater insight into the purpose and value of the study.

“The reason I recorded and shared my life story was to raise awareness that people with learning disabilities can do this. People think we can’t, but we can. Telling our stories helps other people to understand us,” he writes.

While life stories are person centred, they are not necessarily shared to change policy – although this can occur – but to “celebrate life” and the life that the learning-disabled person chooses to tell.

This study invites readers and researchers to consider further the importance of life stories for learning-disabled people, and how using them with research practice will make it more informed. This could improve health and social care practices.

Creative approaches to gathering life stories, such as the use of photographs, music and personal objects, are encouraged, especially for those with complex needs. The people who know them best are encouraged to be part of this process.

While this study gives strong evidence on the value of life stories, collecting them in certain settings is slow. It requires time and sensitivity to the needs of the individual as well as a skilled approach by those gathering and recording the story.

Nonetheless, it is evident that life stories help to shape personalised care and offer opportunities for disabled people to be actively engaged in their life choices.