Juliet Diener reviews studies on how telling stories helps people make sense of life in the time of Covid, self-advocacy’s dynamic history and employing a researcher with a learning disability.

Telling their pandemic stories

Bartlett T, Charlesworth P, Choksi A, Christian P, Gentry S, Green V, Grove N, Hart C, Kwiatkowska G, Ledger S, Murphy S, Tilley L, Tokley K. Surviving through story: experiences of people with learning disabilities in the covid19 pandemic 2020–2021. British Journal of Learning Disabilities. 2022;50(2):270-286. https://doi.org/10.1111/bld.12463

Identifying the importance of allowing people with learning disabilities to share their stories and to have these stories documented as part of mainstream history led to the Surviving through Story project.

Supported by the Open University’s Social History of Learning Disability Research Group, the Generate charity and the Three Ways School in Bath, groups and various advisory members came together to create an interactive, online resource to allow people with disabilities to share their stories through the Covid-19 pandemic.

Offering storytelling as a means to bring about social change, the researchers provided a forum that was safe, accessible and purposeful.

It made sure the disabled person’s voice was heard as they experienced the changes, loss and uncertainty that the pandemic evoked, as well as exploring new ways of being in the world.

For storytelling to be successful, the website “needed to be a space accessible to and directed by people with learning disabilities themselves, allowing content to grow organically in response to the contributions received, the evolving pandemic situation and new ideas”.

The website (https://www.survivingthroughstory.com) offered a sensory experience of sharing personal histories through a variety of accessible means to meet a range of needs.

What the storytellers shared about the pandemic was profound, highlighting sadness, loneliness, fear and despair. However, there was also hope as the stories offered insights, a means of connecting, opportunities to be heard and a creative release while navigating the endless difficulties of the pandemic. Various themes emerged such as grief, as shared by Susie Gentry.

She explains her reason for sharing her story after losing her long-term partner:

“I wanted to help other people. I wanted to tell them what had helped me. Because I had lost Ron, I knew how they were feeling and how hard it can be.”

Ajay Choksi shared his experiences of having the vaccine: “I got my vaccination in March, the Oxford one. Next day, my arm was hurting, when I was trying to use my arm, it was hurting, it was a little bit painful. But no headache or anything. Now I have both of my jabs. Yes!”

The narratives helped the authors to make sense of their experiences and created an opportunity for their histories to be recorded.

This research is filled with rich stories, clear visuals and an engaging website that now offers an archive of experiences of people with learning disabilities during the pandemic. This allows their voices to be heard loud and clear and their contribution to be considered as decisions are made and policies written.

History of self-advocacy

Walmsley J, Davies I, Garratt D. 50 Years of speaking up in England – towards an important history. British Journal of Learning Disabilities. 2022:50(2):208-219. https://doi.org/10.1111/bld.12453

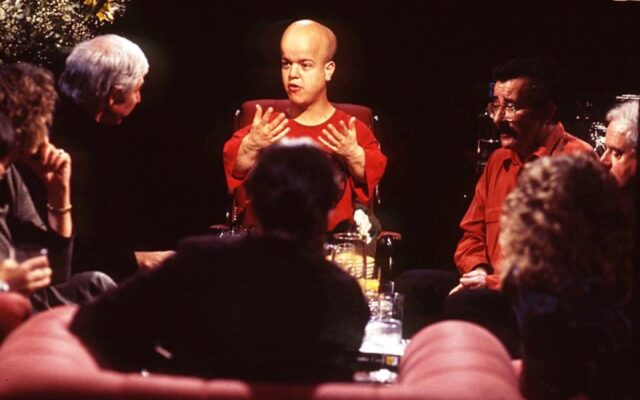

Celebrating 50 years of self-advocacy, which prompted change for and by people with learning disabilities, this research project was set up to capture the histories of this significant movement. As people with learning disabilities are under-represented within scholarly and historical writings, the authors worked to make sure this history was recorded.

With authors donning masks and meeting between lockdowns, the research was generated through 10 questions that were answered by early leaders of self-advocacy, allies and supporters.

With no funding and pandemic restrictions, the authors found technology was a welcome support as interviews were conducted mostly online.

While attempts were made to interview most of the leading advocates of the time, it posed problems. Nonetheless, those involved offered a vast range of experiences and reflections.

Following the interviews, a timeline was drawn alongside various themes from the transcripts. The timeline is significant, giving context to and illustrating the development of the actions of self-advocacy, and offering insights from both individual and group advocacy that “preceded the founding of collective self‐advocacy in England”.

Self-advocate Wendy Perez stresses: “I have always spoken up for myself – even when younger, I made my own decisions. I just did it. My family encouraged me… You shouldn’t need an organisation to speak up. It shouldn’t be that way.”

The early gatherings of self-advocates were deemed as participatory with the emphasis being on “mutual learning and understanding”. In the 1980s, this shifted, with gatherings becoming more about promoting independence and rights.

Walmsley, Davies and Garratt give a fascinating account of how various events and policy decisions led to the ever-evolving history of self-advocacy.

They leave the reader with a thirst for more as this research paper is merely “a first step in recording the stories of early leaders of self‐advocacy and recognising their contributions”. They name the difficulties and misses alongside the achievements and successes, prompting a call to action.

As self-advocate Danielle Garratt concludes: “If we don’t record these stories, they will be lost forever and people will never know how our movement started.”

Recruiting a researcher

Anderson RJ, Keagan‐Bull R, Giles J, Tuffrey‐Wijne I. “My name on the door by the professor’s name”: the process of recruiting a researcher with a learning disability at a UK university. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1111/bld.12477

The value of people with learning disabilities as co-researchers has been established in recent studies and is shared in this article. However, being employed within a tertiary education setting is more unusual and requires adjustments by universities.

People with learning disabilities bring value to their role in sharing lived experience in the field of inclusive research. This value should be supported through paid employment and opportunities to contribute actively to research projects.

This study identifies significant barriers to employment, which begin with the application process.

For the applicant, concern regarding a loss of benefits from taking up work was a notable barrier. While initial barriers in managing a contract and simplifying the application process could be addressed, the long-term management of supporting a learning-disabled employee requires flexibility in approach and budgeting to allow support to continue beyond the interview. Finding solutions to the barriers identified meant the applicant could accept the position.

The research presents a variety of perspectives, namely the line manger seeking to fulfil a role, the human resources manager who managed the recruitment process and the successful applicant who was offered the role of research assistant.

Recruiting and supporting a research assistant with learning disabilities need a whole-team approach as planning and working together require ongoing support and adjustments to working culture.

The findings in this paper offer guidance on making employment more accessible to people with learning disabilities.

Research assistant Richard Keagan‐Bull wrote about his experience of working in research in the last issue. He says: “It is important to make things accessible for people with a learning disability as it’s important for them to be able to do jobs in an equal and accessible world.”