Event held against ban on campus-style homes

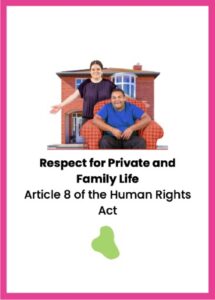

Almost 200 people gathered at a conference campaigning to protect the future of congregate living for adults with learning disabilities.

The Care Quality Commission (CQC) issued a guide in 2020, Right Support, Right Care, Right Culture, with the aim of helping autistic people and those with learning disabilities live in the community with more choice, dignity and independence.

However, the guide states that the CQC will not approve new group homes or campus-style accommodation as it believes such homes isolate residents from communities.

Family-led Our Life Our Choice held the event at Woburn House Conference Centre in London this spring.

The event, Learning Disabilities: Challenges and Choices in Care and Accommodation, highlighted how congregate settings can provide high-quality, cost-effective care.

Campaigners said blocking new facilities violated UN and European human rights conventions as it would deny people choice.

Performance course aims to raise profile

A performance-making diploma led by learning disabled and autistic theatre company Access All Areas has won two years of funding from Netflix.

The diploma, delivered with the Royal Central School of Speech and Drama, University of London, is thought to be the world’s only course designed by and for learning disabled and autistic creatives.

It aims to increase representation in TV and film, where people with learning disabilities and autism remain significantly underrepresented, both in front of and behind the camera.

The course builds confidence, communication, and independence, with classes co-led by learning disabled and autistic professionals.

Since its 2013 launch, 79% of graduates have secured professional roles, including work with major broadcasters and theatres.

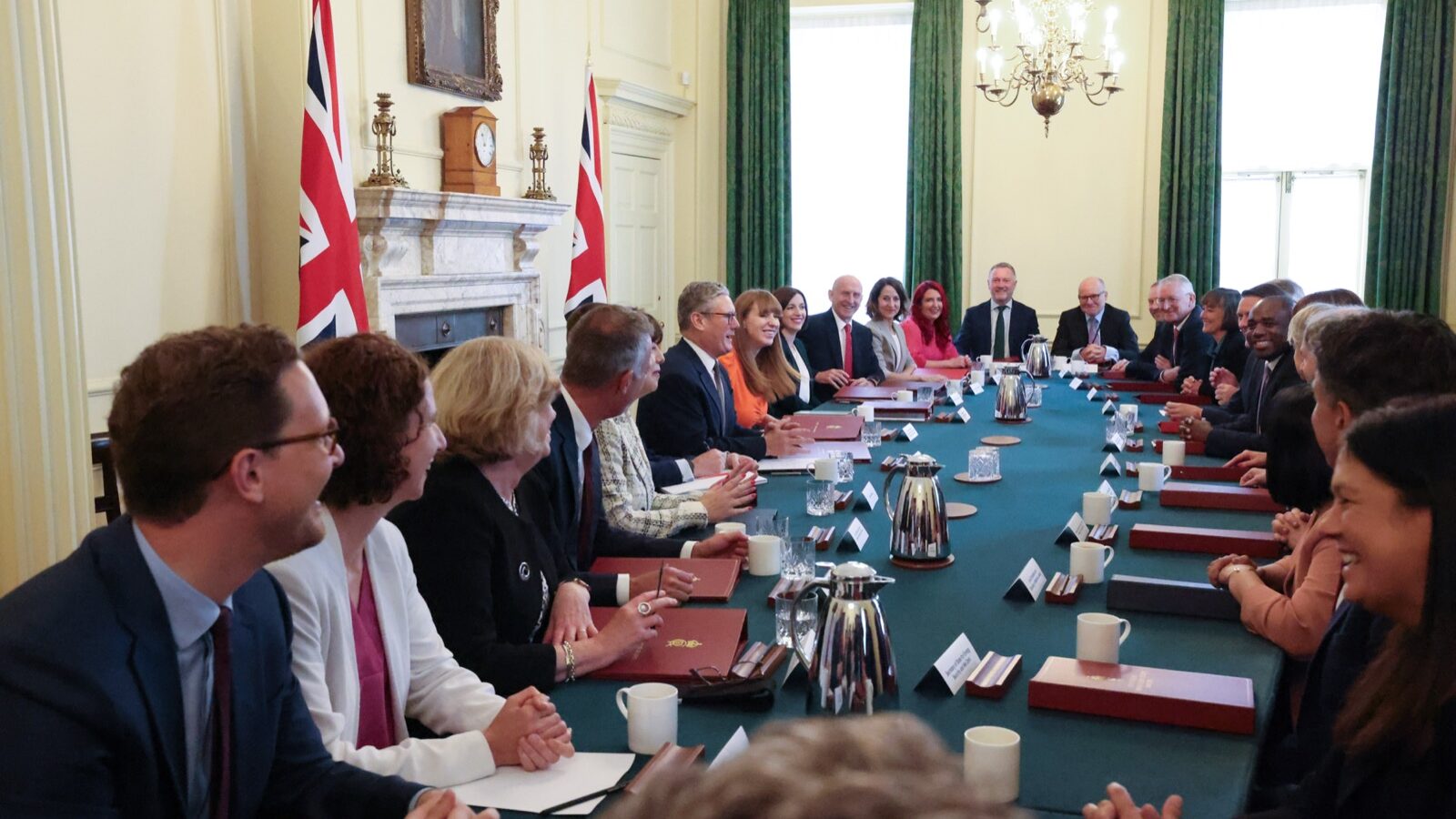

Mass lobby opposes welfare cuts

Activists from across the UK gathered at parliament recently to confront MPs about disability benefit cuts.

Around 40 MPs attended the mass lobby organised by the Coalition Against Benefit Cuts, Disabled People Against Cuts, WellAdapt and Disability Rights UK, which said: “Never has it been more important to have your voice heard.”

No ‘outsider’: sculptor in line for Turner art prize

The shortlisting of Nnena Kalu for the Turner Prize is an important moment in the relationship between learning-disabled artists and the art world, writes Simon Jarrett.

The Turner Prize judges were wowed by her astoundingly striking large-scale creations, produced in the main from humble VHS tape.

One judge commented “most of all the jury was simply hugely impressed by Kalu’s assured and very beautiful sculptures”.

The importance of this is that Kalu has not been herded into a patronising category of outsider art.

Certain types of artist can be dismissed as interesting but not quite the thing, and may be gently but firmly nudged from the “real” art world.

Viewing the world through the prism of her learning disability and her largely non-verbal communication may indeed have shaped the enormous expressive power of her art.

Nonetheless, Kalu has been assessed and judged purely on her considerable artistic merits.

News briefs

Our new chair of board

Community Living is delighted to announce it has appointed Rhidian Hughes, chief executive of Voluntary Organisations Disability Group, as chair of trustees. He will work alongside board members to support the editorial team and the magazine’s strategic direction.

Day against detention

The Bring People Home from Hospital campaign held a day of action to protest against disabled individuals being held in mental health units. Campaigners delivered a letter to the Department for Health and Social Care calling for an end to the detention of people in psychiatric settings.

Mental health referrals rise

Nearly 30% more children have been referred to mental health services for autism and ADHD than last year, despite these not being mental health issues, according to the Children’s Commissioner.

Abuse on public transport

Disabled people often face abuse, harassment and hostility while using public transport, according to a study by United Response. Findings show low reporting, a lack of support and lasting trauma. The charity called for safety measures and greater accountability in the transport and justice systems.

Finance fears for housing

Over 150 organisations have warned the government

that a supported housing crisis threatens 70,000 homes for vulnerable people in England owing to financial issues.

The National Housing Federation urged the government to allocate £1.6 billion annually to provide safe, affordable housing.

All Update stories are by Saba Salman unless otherwise stated