Jean Vanier, who died this year, founded the L’Arche community movement in the 1960s –

one of the earliest efforts to overcome institutionalisation – and was a profound thinker on

disability and the human condition. Simon Duffy reflects on his influence and legacy

Jean Vanier: ‘There is a revolution going on. At the heart of this revolution are not the powerful, the wealthy or the intelligent. It is people with disabilities who are showing us what is important’

The first time I heard Jean Vanier was in 2015 in an upstairs room in the UK parliament.

The talk was Living Together for the Common Good: Why do the Strong Need the Weak? Vanier’s starting point was not ‘What makes us strong?’ but ‘What makes us human?’

He reflected on the enlightenment idea of humanity, with its ideal of the rational, competent and goal-achieving human, which is central to modern thinking about the self.

He observed how self-defeating this ideal can become; the more individuals advance, the more they must leave others behind. We think we are building but, all the time, we are simply destroying.

Instead, for Vanier, we must begin with acceptance and love. He drew on the words of St Paul: ‘Love is patient, love is kind. It does not boast, it is not proud. It does not dishonour others, it is not self-seeking.’

For me, one of the most memorable points of the evening was when Vanier pointed out that what comes first is patience. The modern view of love so often slips into that dangerous enlightenment mode where all the focus is on what we do in the name of love. Love becomes another badge that we award ourselves. We strive to do, to change and to improve – yet so often we fail to just be with, meet and accept each other.

Movingly, Vanier told the story of a male prostitute in Australia who, dying in the arms of a member of L’Arche, said: ‘You’ve always wanted to change me – but you’ve never met me.’

In the process of fixing others, we lose sight of our very humanity – our essential fragility and our need for love, belonging and contribution. Humanism becomes inhuman.

Wonderfully different, fully human

This reminded me of my first experience of people with learning disabilities, in an institution in the south of England.

The buildings and the behaviour of the staff struck me with horror; the most important experience for me was that it showed a different way of being human.

I was a highly competitive young man, with some modest academic abilities and a raging desire to work, achieve and win.

Yet here were people who had been taken out of that rat race but were still fully human. Here was goodness, calmness, dignity, care, curiosity, play, challenge, suffering and fear. Here were people who were certainly different but wonderfully so.

For me, this experience challenged my notion of who I was and the purpose of my life. Paradoxically, it also turned into a mission which, for better or worse, has driven most of my decisions over the last 30 years.

So I worked to help people leave institutions, take control of their lives, make friends and contribute to communities – to become full citizens.

It became a project and, in the light of Vanier’s critique, I can see that a project like that is also full of dangers. It can lead one into feelings of self-importance and it can tempt one to see others as the means by which your goals can be achieved – even if those goals seem noble.

Vanier’s approach was different. As he put it, the mission of L’Arche is less about what it achieves (although it achieves a lot) and more about the message that is inherent in its way of being – that we must meet together as fellow humans. In the meeting of the strong and the weak, each is transformed. The weak may be supported, but the strong also get the chance to find out what really matters and who they really are.

Vanier once wrote: ‘I must say that for myself it has been a transformation to be in L’Arche. When I founded L’Arche, it was to ‘be good’ and to ‘do good’ to people with disabilities. I had no idea how these people were going to do good to me. The people we are healing are in fact healing us, even if they do not realise it’ (Vanier, 2004).

In fact, nobody is really weak or strong. The desire to be among the strong and to avoid the weak is a symptom of society’s failure to welcome all and to comprehend the true value of each individual.

It is important to note that Vanier is not attacking the government, the powerful, professional experts or policymakers. He is not saying they are wrong, stupid or evil. Instead, he is acting out the very issue he wants people to understand: we must meet each other; we do not need to use each other. The world is not a puzzle to be solved. We must live and act with integrity and love. We cannot hope to be the answer to every question. We must be true to our own gifts and find the role that is right for us.

New revolution

The second time I listened to Vanier, he began his speech with this rallying cry: ‘There is a revolution going on. We are beginning to realise that everyone, every human being, is important. We are beginning to see that every human being is beautiful.

‘At the heart of this revolution are not the powerful, the wealthy or the intelligent. It is people with disabilities who are showing us what is important – love, community and the freedom to be ourselves.’

The context was so interesting. He was receiving the Templeton Prize at St Martin in the Fields on Trafalgar Square. This tiny, frail individual was standing among the powerful with a twinkle in his eye and a smile on his lips and overturning the most important value system upon which their power rests – not power, not even money but their faith in their own superiority.

Vanier captured exactly the fundamental flaw in the thinking and behaviour of the powerful; they behave as if the point of life is to climb higher and higher, to even clamber up upon the backs of the weak. But where are they going? What will they find when they get there?

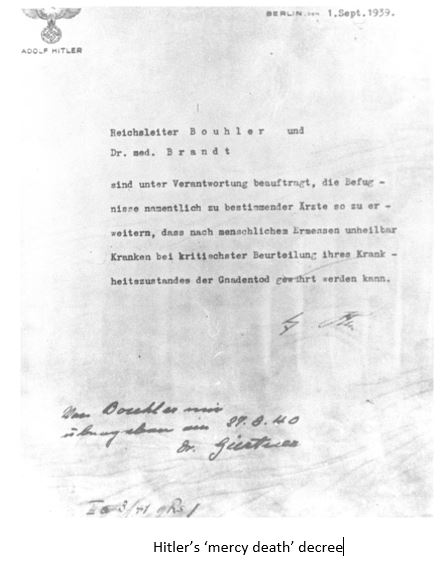

I think that Vanier’s challenge to the powerful is right. However, I also feel that the weak cannot afford to wait for the strong to wake up to their true needs. Mental handicap ‘hospitals’, like the one I visited and which, as Vanier rightly said, ‘crush disabled people’, had to be closed.

The reason they were closed was because families, people with disabilities and their allies came together to work and to lobby to bring about their closure. It did not happen by accident or because some politician suddenly woke up to their injustice.

“I founded L’Arche to ‘do good’ to people with disabilities. I had no idea how they were going to do good to me“

We do need to organise and to join the political process. Unless people with disabilities and families are present in that process – just as they should be present at every other level of community life – they will not be able to defend their rights or interests. The presence of people with learning disabilities within the political process may even bring some honesty and humility to that strange world.

Real, mucky community

What might Vanier’s revolution look like for the welfare state as a whole?

As he says, we need community, but real community is mucky, a little bit crazy and often quite annoying. But it is only community that can create the beauty, truth and the love we all need.

We must reconsider many common assumptions about how best to organise society and the welfare state. Many practical and social changes are needed:

Basic income We will need to secure everyone’s income without relying on enforced labour, stigma and shame. We need to recognise the many different contributions people can make to community life, not force everything through the sausage machine of paid employment.

Inclusive education Why do we teach our children that life is all about fitting into some tightly defined hierarchy of meritocratic values? Surely, every child must be supported to discover their own gifts and find their own path in life.

Independent living Everyone belongs and everyone can have a life of meaning and contribution. Needing extra support should not be a barrier to this. The social care system must be redesigned to enable people to control their own lives and their own support.

Inclusive communities We must not force people out of communities because their income is too low, their skin colour is wrong or they have extra needs. Communities must welcome difference and offer people homes and places, real and virtual, where people can meet, discuss and create together.

Constitutional reform Ultimately, we need to live in democracies that enable power to be decentralised and enable citizens and communities to take greater responsibility for shaping their destinies, within a framework of human rights.

Social problems today reflect the challenges Vanier describes. Justice does not mean establishing some neutral set of rules and rights that enable individuals to just get on with their lives. It means far more – living together, valuing each other and creating a better world together.

Simon Duffy is director of the Centre for Welfare Reform: www.centreforwelfare reform.org

References

Vanier Jean (2004) Drawn into the Mystery of Jesus through the Gospel of St John. Mahwah, New Jersey: Paulist Press

Further information

Jean Vanier official site: www.jean-vanier.org/en

Jean Vanier 1928-2019. www.larche.org/web/jeanvanier/home

Shared lives in L’Arche communities

Jean Vanier (1928 -2009) founded L’Arche, an international federation of communities for people with learning disabilities and those who assist them.

- The first L’Arche community began in 1964 when Jean Vanier welcomed two men with learning disabilities into his home in France

- Today, there are 147 communities in 35 countries on five continents

- In L’Arche communities, people share their lives together and build a society

- L’Arche philosophy is rooted in Christianity, but communities are open to people of all faiths and none

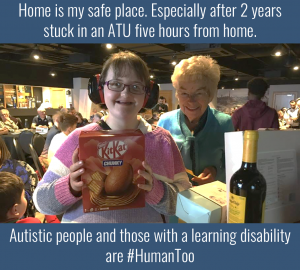

Figure 1 Inclusion is about being and belonging in a community that goes beyond formal equality

Figure 1 Inclusion is about being and belonging in a community that goes beyond formal equality