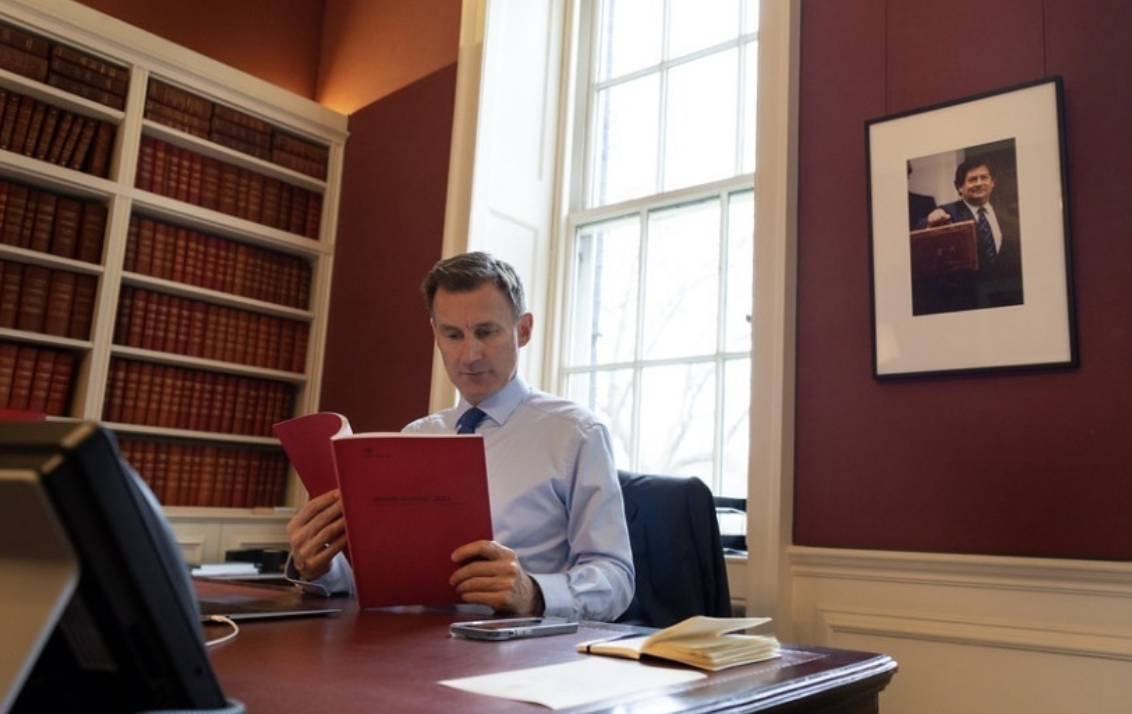

Chancellor of the exchequer Jeremy Hunt presented his spring budget in March – at the same time, his government issued the health and disability white paper.

The white paper provides further details of plans for employment support for disabled people in the budget. It also includes proposals for changes to the benefit system that, if and when made, will affect many people with a learning disability who claim means-tested benefits.

The government said the measures were designed to “support and encourage people into work”.

These include the following.

- Abolition of the work capability assessment. This is used to determine whether a claimant has limited capability for work or work-related activity, and if they can get an extra payment in contribution-based employment and support allowance or universal credit (UC). Under the proposals, it will be replaced by the assessment used for personal independence payment (PIP). A person receiving PIP would be entitled to the extra payment

- A new “health element” in UC. This will replace the limited capability for work-related activity element in UC

- Support from work coaches will be extended to more long-term sick and disabled claimants. They will give advice, coaching and support to help them secure a job

- People claiming UC will be required to agree and meet intensive work-related conditions, with an increase in the amount they need to earn before they have to meet only light-touch requirements as a condition of getting the benefit

- UC claimants who are the main carer of a child will have increased requirements to look for work and/or increase their working hours but with additional work coach support

- The sanctions regime has been toughened up for cases where claimants fail to meet work conditions they need to fulfil to maintain a claim or choose not to accept “reasonable” job offers. Claimants with a disability may have voluntary and mandatory work-related requirements imposed by their work coach and will be subject to sanctions if they do not comply

- A new voluntary employment scheme for disabled people – universal support – will try to match people in England and Wales with job vacancies and fund training and workplace support. The plan is to help up to 50,000 people a year with up to £4,000 spent per person.

A couple of measures in the budget affect families. Working households receiving UC can now claim back up to 85% of their childcare costs at higher rates, up to a maximum of £951 a month for one child or £1,630 for two or more children. Thirty hours of free childcare is to be provided for children aged over nine months; this is being phased in between April 2024 and September 2025.

The government said before the budget that millions of the lowest-income households in the UK would continue to get financial help with the cost of living. These closely mirror the cost of living payments operational since 2022.

They are:

- Up to three cost of living payments of £300 to people in work receiving means-tested income benefits, including UC, tax credit or pension credit. These are being paid in three instalments between May this year and spring 2024

- A disability cost of living payment of £150 for a person who gets any of the main disability benefits on a certain date. These include attendance allowance, PIP and disability living allowance for adults or children; in Scotland, these include adult disability or child disability payments

- Pensioner cost of living payment: people of pensionable age who are entitled to a winter fuel payment for winter 2023-24 will get an extra £150 or £300.

Many of the major changes proposed in the white paper will take some time to become reality, and we will report on the changes as and when they happen.

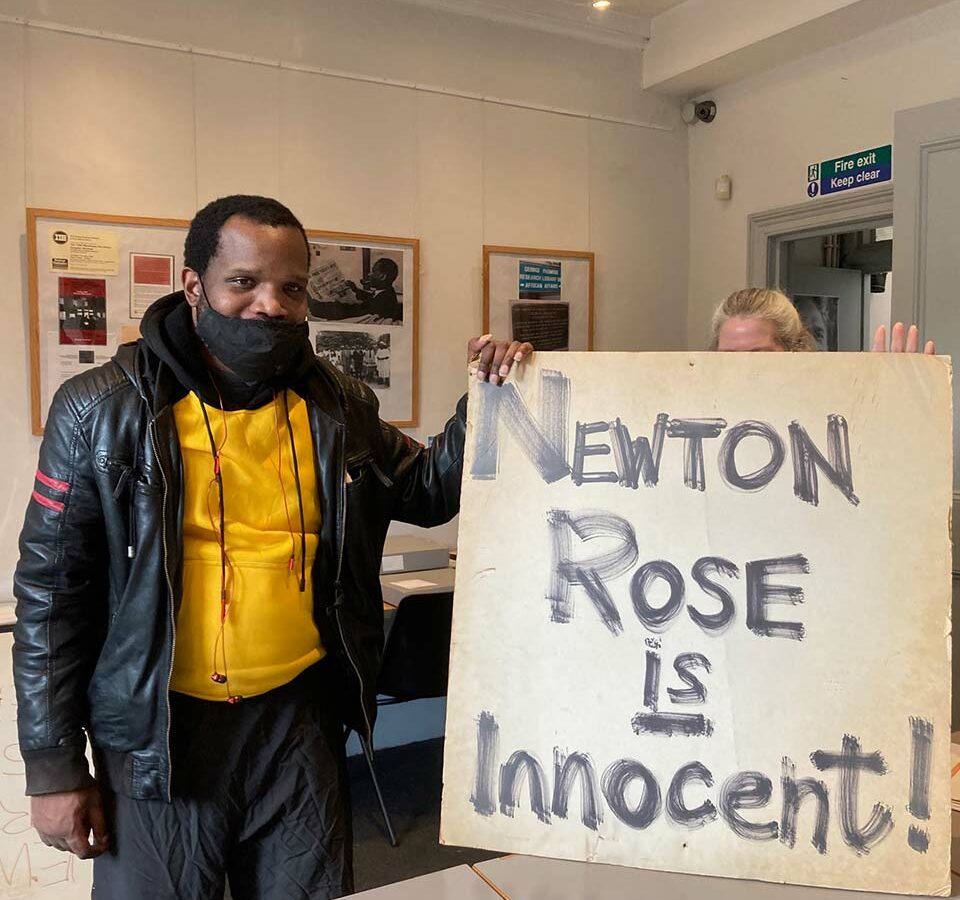

This is an eye-catching book, not least because of its bold cover.

This is an eye-catching book, not least because of its bold cover.

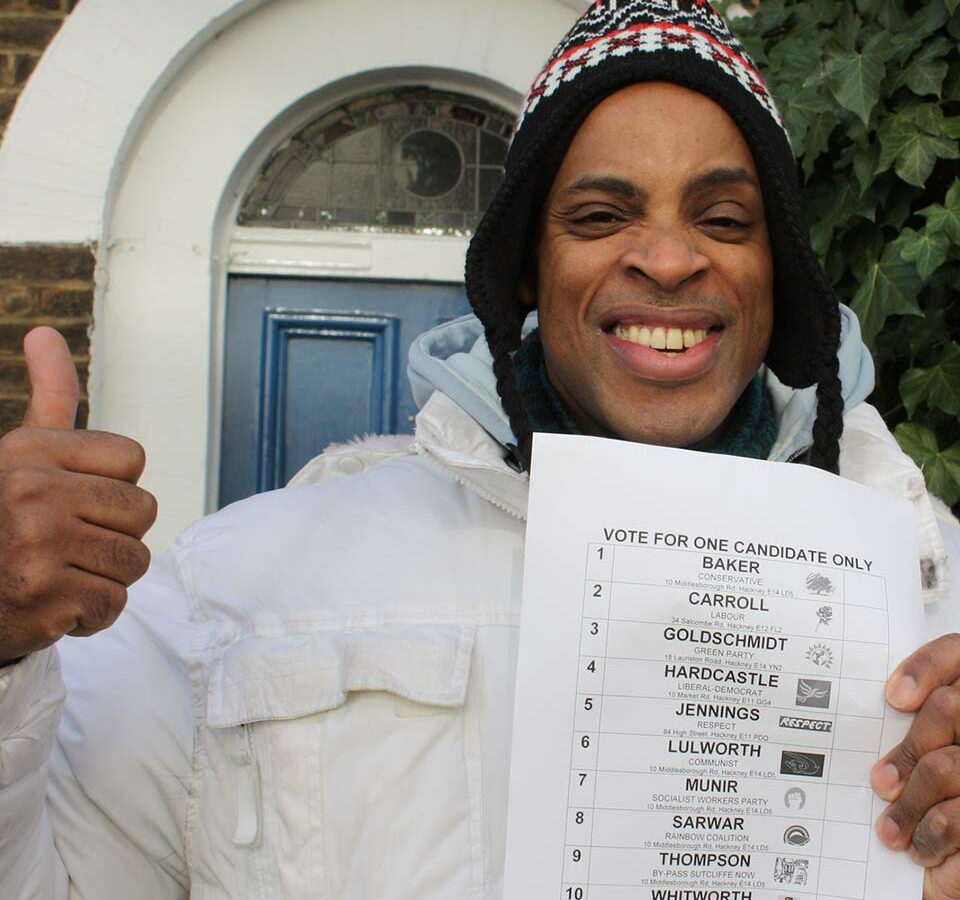

Future materials could be produced in a much shorter period. I hope the process we developed with one black history archive will encourage similar organisations to make their own collections more accessible.

Future materials could be produced in a much shorter period. I hope the process we developed with one black history archive will encourage similar organisations to make their own collections more accessible.