“Sometimes I rush into things and it goes pear shaped. I don’t think everything through. I want my supporters to help me understand the situation, so that I can think through the right road for me. I want them to help me understand.”

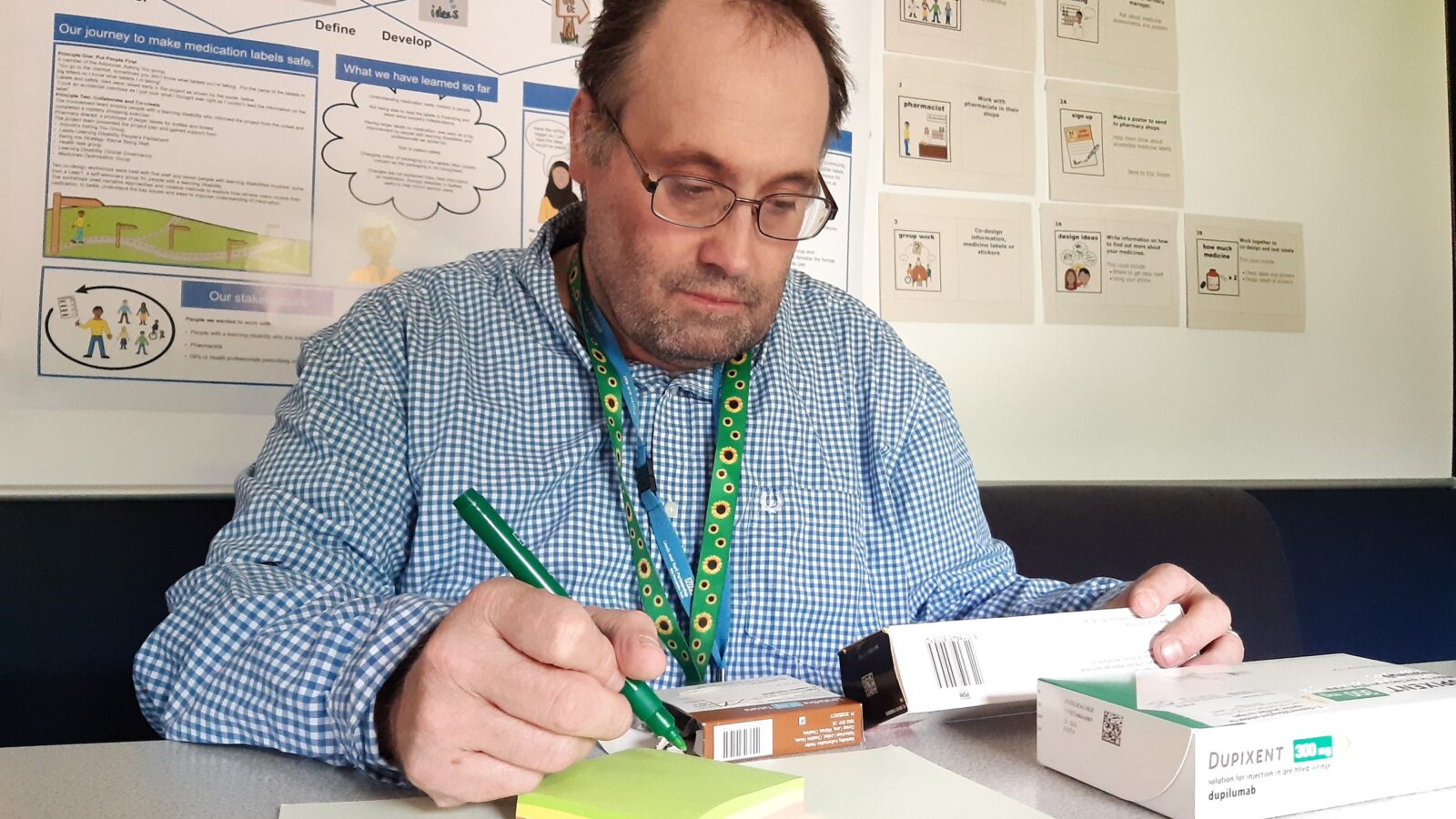

This comment from David Jeffrey, a self-advocate from London, sums up why Paradigm launched supported decision-making workshops and a free guide (available on our website) for anyone in a support role. Our training organisation co-produced the guide with self-advocates.

Enabling someone to decide for themselves is a basic human right highlighted in the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, the Mental Capacity Act 2005 and the Care Act 2014.

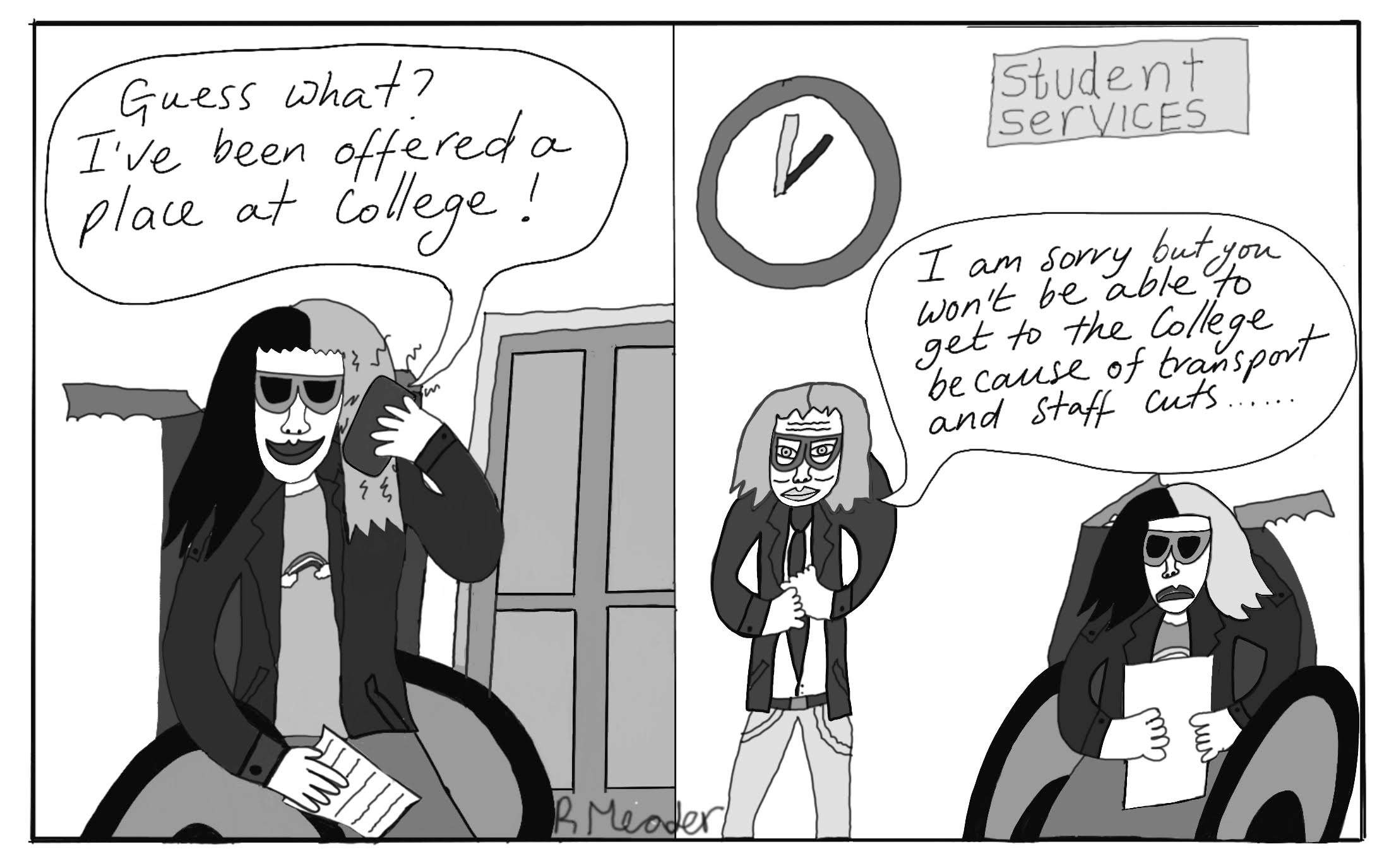

Often people will be offered only one option, for example a move into residential care.

The Mental Capacity Act should uphold people’s rights to make decisions, from small everyday decisions such as what to eat to bigger ones such as over where to live.

But often, people with a learning disability are stopped from making decisions because others think it unwise.

If a decision seems risky, it is important to check if the person understands the risks and choices. They may need support to consider the options or find better ones.

Lucy Series, lecturer at the School for Policy Studies at the University of Bristol, contributed to our guide.

“Most people take for granted that they will make key decisions about their lives. We also know that being able to make decisions about our own lives is critical for wellbeing,” she says.

Supported decision-making involves:

- Asking how someone wants to be supported

- Asking if there is anyone they would like (or not like) to help them make the decision

- Making or finding accessible information about the options

- Helping someone find out about the choices available

- Support to understand and weigh up the pros and cons of each option

- Help to identify any risks and explore how to address them

- Supporting the person in expressing their feelings about each option.

Often people will be offered only one option, for example a move into residential care.

Take one young man we know – let’s call him Tim – who does not use many words to communicate.

He was supported to take part in weekly swimming sessions but these usually ended abruptly, with support workers taking him home because he was too upset.

One of the home team who knew Tim well was asked to go along to find out what was happening. As they drove there, Tim was happy to be going out, clapping, cheering and saying “car”.

But, when they got to the road leading to the pool, he became upset, with his distress escalating when one of the staff got out of the car to get his wheelchair and another tried to remove his seatbelt.

The person who knew him asked if anyone had considered that Tim did not want to go swimming – maybe he didn’t need to return home but try something different.

She asked Tim if he wanted to go for a drive as he had loved the journey. He stopped shouting and, as they drove off, shouted: “Hooray.”

This distressing experience could have been prevented if staff had offered him support to decide on the activity.

Our guide includes a decision flow chart to help anyone in a support role to think through this process.

It includes questions, such as what kind of issue is involved: a big decision or a smaller one? Does the person prefer a certain communication method, so they can fully understand the options?

The resource also includes downloadable checklists to help keep the person at the centre of the decision-making.

We need to be upholders and campaigners – not gatekeepers – in upholding people’s rights so they can, with appropriate support, steer their own way through life.

Sally Warren is managing director and Jo Giles is associate at Paradigm

An education professional who I (wrongly) assumed was an expert told me that the reason my son didn’t want to go to school was that he knew I was “a soft touch”. She told me I needed to put my foot down.

An education professional who I (wrongly) assumed was an expert told me that the reason my son didn’t want to go to school was that he knew I was “a soft touch”. She told me I needed to put my foot down.