William Frederick Windham was born into a wealthy Norfolk landowning family in 1840. After the death of his father in 1854, his guardianship passed to his nervous and distracted mother and his formidable war-hero uncle, General Charles Ash Windham.

Just before he came of age, William Windham fell in love with Agnes Willoughby, one of the most celebrated and (thanks to her many admirers) wealthy courtesans of her day. She was also by all accounts a shrewd businesswoman.

Windham spent what he could afford on wooing her and, after he came of age in 1861, settled a vast sum on her when they married three weeks later. During their time together, he also bought her jewellery costing the equivalent of £600,000 in today’s money.

Family bid for control

Horrified by what he saw as his nephew’s reckless behaviour and even more reckless spending, General Windham launched a commission for lunacy.

His intention was to prove that William Windham was an “idiot” or “imbecile” of some description, and therefore incapable of managing his own affairs. The marriage would then be annulled and the family estate and all assets brought back under the family’s control.

He loved to wear uniforms and impersonate officials. While dressed as a railway guard, he almost sent one train into the path of another

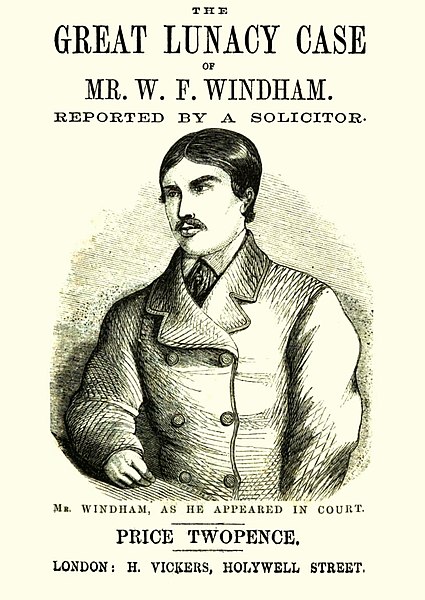

The Windham case was heard before a jury and involved 140 witnesses. It ran for 34 days over 1861-62, racking up tens of thousands of pounds in legal fees.

Evidence focused not only on William Windham’s profligate spending but also on his “dirty” habits, such as vomiting at the table, and his flamboyant, “inappropriate” behaviour.

The latter included consorting with the lower classes, making unsuitable noises and displays of emotion at formal events such as his father’s funeral as well as the buffoonery that had earned him the suggestive nickname of “Mad Windham” while at Eton.

Windham was undoubtedly eccentric. In particular, he loved to wear uniforms and impersonate officials. Dressed as a police officer, he “arrested” women on Haymarket and accused them of soliciting, and had torn round the Norfolk lanes in a hijacked mail cart dressed in a post-office uniform.

He did most damage dressed as a railway guard. On one occasion, he almost sent one train into the path of another through injudicious use of his guard’s whistle, and was also known to bribe staff to allow him to drive the trains.

At least one of his terrified passengers wrote to The Times expressing the sincere hope

that the commission of lunacy would at least put an end to this latter behaviour.

But it was not to be. Unimpressed by the sight of disunited and bickering medical men who simply could not agree on whether Windham was an imbecile, the jury decided that the whole case was an affront to the freedom of the individual and an Englishman’s inalienable right to eccentricity.

Windham was found to be of sound mind, and free to continue using his dwindling fortune to terrorise the passengers of East Counties Railway.

John Langdon Down, the physician who first described Down syndrome, was appalled at the verdict.

Reflecting on the trial some 25 years later, Down made much of Windham’s tendency to slobber and drool. For him, this was irrefutable proof of Windham’s idiocy and incapacity.

He claimed that trained medical men such as himself would have had Windham locked safely away, thus avoiding the (to Down, inevitable) events of Windham’s post-trial years: a costly divorce, bankruptcy and an early death.

But the contemporary press were just as certain that the jury had been correct in their verdict, as they had resisted the medicalisation of eccentricity. As The Times observed, any other verdict would have been “insane”.

Jarrett S. Those They Called Idiots: the Idea of the Disabled Mind from 1700 to the Present Day. Reaktion Books; 2020

Heaton T. A Scandal at Felbrigg: the True Story of the Notorious Miss Willoughby and “Mad” Windham. Bosworth Books; 2012