Fancy a challenge? Try this for size: you start as Mencap’s new chief executive in early 2020, just two months before the UK’s first lockdown, and face all the difficulties of the pandemic in an organisation you are just getting to know. Not enough? Alright. Let’s throw in a complete management restructuring of the organisation and a new strategic plan in the first year.

“It’s been quite incredible,” she says. “I am really, really, proud of Mencap when I look back over the last 12 months – first and foremost in terms of the personal support services that we have continued to provide all through the pandemic. “We have lost people we support and we have lost some colleagues to Covid. We had to source essential PPE when stocks were limited. We had to deal with ever-changing guidance in the first few months.”

Colleagues have had to make great sacrifices, she says, “but they have been creative and brought joy to the people that they support”. Mencap has clearly had a good public profile during the pandemic and Harris is proud of its campaigning and lobbying of the government. “For example, when the NICE [National Institute of Health and Care Excellence] clinical guidelines were produced and, in our view, conflated having support needs with clinical frailty, we were right on that one and got that changed,” she says. Harris feels Covid catapulted her into fast-tracking relationships with ministers and senior civil servants. “I have been really pleased at how accessible some ministers and senior people have been. I would say that the care minister and even the cabinet secretary for health and social care have needed us. And I don’t mean Mencap necessarily – I mean third sector organisations like us – almost as much as we have needed them”

I ask about her route to Mencap and Harris tells me her first job was a police officer; she spent 11 years with the Metropolitan Police. “Even then, I was much better suited to the social side of policing. I specialised in child protection and wasn’t quite so good at catching the bad guys,” she says with a smile. “I suppose I always had a leaning towards more social issues such as equality and poverty.” After her five-year-old son was diagnosed with fragile X syndrome and a learning disability, Harris gave up work for a while and moved to Scotland to be near to her husband’s family. During this time she studied for an Open University degree in health and social care and took a particular interest in the learning disability module.

Following that, Harris worked for the NHS in public health, before moving to Aberdeen Foyer, a homelessness charity, as deputy chief executive. In 2008, she became chief executive of Cornerstone Community Care, which offers support across Scotland to people with learning and/or physical disabilities, among others. Harris stayed at Cornerstone until late in 2019. On arriving at Mencap, she found “a very values-driven charity, focused on delivering the charity purpose, and concentrating always on people with a learning disability” However, she adds, there were “also some things, as you would expect, that I felt could be improved”.

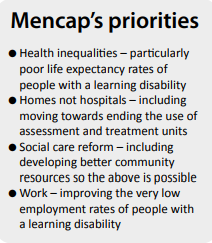

In her first year, she implemented a new organisational structure based on five directorates. Harris says that rather than a traditional hierarchy, the new structure can be visualised as a wheel. I nod sagely (well, it sounds good to me…). Our Big Plan was developed with people with a learning disability and their families as well as organisational partners. Harris says that the plan focuses less on what Mencap will do and more on supporting people and communities to develop their own capabilities. Mencap’s overarching vision is for the UK to be “the best place to live in the world if you have a learning disability”. It has set four overarching priorities (see box). Harris adds that the plan is all about achieving that vision and being “a better partner, a better collaborator” That is interesting, I say, because sometimes Mencap has been seen as a little aloof, claiming to be “the voice of learning disability” while not always working with others.

In her first year, she implemented a new organisational structure based on five directorates. Harris says that rather than a traditional hierarchy, the new structure can be visualised as a wheel. I nod sagely (well, it sounds good to me…). Our Big Plan was developed with people with a learning disability and their families as well as organisational partners. Harris says that the plan focuses less on what Mencap will do and more on supporting people and communities to develop their own capabilities. Mencap’s overarching vision is for the UK to be “the best place to live in the world if you have a learning disability”. It has set four overarching priorities (see box). Harris adds that the plan is all about achieving that vision and being “a better partner, a better collaborator” That is interesting, I say, because sometimes Mencap has been seen as a little aloof, claiming to be “the voice of learning disability” while not always working with others.

Harris acknowledges she has heard such things, although “there have been wonderful partnerships in the past”. She adds that “there is a huge emphasis on partnership working, collaboration and supporting people and other organisations” in the new plan. Mencap has dropped the “voice of learning disability” strapline although it will take a while for it to be removed from everything, she says: “It is painted on the front of our office in London – and taking that down is obviously not a small job. But you won’t see us using it going forward.” I ask whether she considers Mencap to be a service provider that campaigns or a campaigning organisation that provides services. Her ready answer – that service provision and campaigning both inform and strengthen the other – clearly shows she has been asked this before.

The plan describes service provision as one of Mencap’s five “levers”. The others are: campaigning and lobbying; information and advice; research; and community-led delivery, which concerns “supporting people to find solutions in their own communities”, she says. Without giving much away, Harris says that “the balance between those five levers might shift over time”

I wonder whether Mencap could do more to help people with profound and multiple learning disabilities, who are often excluded even within the learning disability world. Harris says: “We make every effort to involve people with a more profound learning disability in our activity but, if we find it challenging, then you can understand how society does. But you can’t say: ‘It’s difficult so we’re not going to do it’. “We have to use every skill, every talent, every communication method, every engagement tool that we have at our disposal to make sure people with more profound disabilities are heard and that they lead the lives that they want to lead. I don’t think we’ll stop trying in that regard.”

Court case on overnight wages

Mencap recently won a court case which means that employers do not have to pay the minimum wage to staff doing sleep-in cover and can pay a lower sleep-in rate. Did Mencap’s stance damage its relationship with its own staff? Harris tells me she understands the disappointment many staff felt at the court result. Although it won the case, Mencap pays staff providing sleep-ins (or, as Mencap prefers to say, “overnight support”) on minimum wage rates.

However, she admits to being relieved that Mencap does not now face a £15 million bill in back pay, adding: “Remember, this wasn’t money that we ever had in the first place.” Mencap is working with trade union Unison “to call for a proper workforce strategy that values people who do this most important work”. It is also calling on the Low Pay Commission to review pay for overnight support. For the future, Mencap remains committed to its improved rates of pay: “We are not going to go back to paying a flat rate for overnight support,” Harris says.

Death in Mencap’s care

I feel I have to raise the sad death of Danny Tozer, who passed away while in Mencap’s care. While an inquest in 2018 cleared Mencap of any responsibility for his death, the coroner said the quality of communication with Danny’s family was not satisfactory.

Mencap has continued to receive public criticism for the combative approach of its lawyers at the inquest and, apparently, for failing to make direct contact with Danny’s family. All this happened well before Harris was in post but I ask her what lessons she has learnt and whether she has been able to reach out to the Tozer family. She replies that of course lessons are learned “when an organisation and people who work within that organisation go through such a traumatic event”. But she is not willing to say much more: “I don’t think it is appropriate to speak to anyone about Danny and his life and his death or, indeed, talk to anyone about what contact I may or may not have had with Mr and Mrs Tozer because it is a very private family matter, and I would only do that with the family’s consent. “When we still hear people criticising us, all I will say is they don’t know what has or hasn’t happened since I have been in post.”

I am left with the feeling – which of course I cannot substantiate – that Harris may have been able to reach out to the family and make a better connection. On a happier note, I mention I recently interviewed Katie Price, whose son Harvey is now a Mencap ambassador (page 14). “He’s a brilliant young man, isn’t he? And the recent documentary exposed learning disability in a positive way to a much wider audience. So yes, we are grateful to him coming on board.” After that, it is time for me to wish Harris a successful and more settled year, in which hopefully she can meet more of her colleagues face to face rather than just screen to screen.