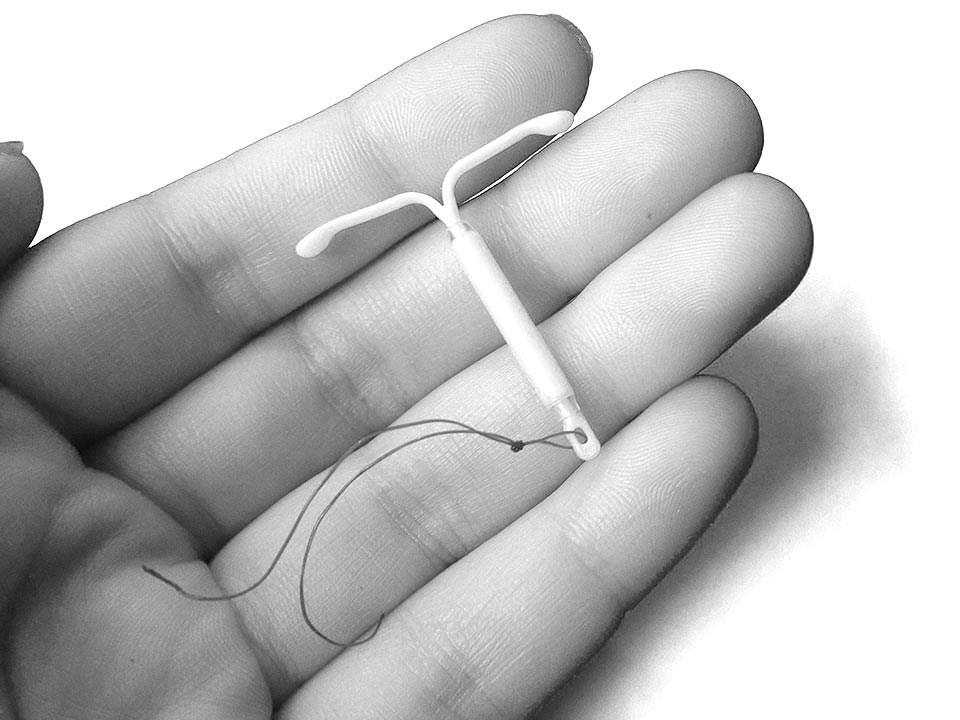

Women with learning disabilities are often encouraged to use long-term contraceptives, such as intrauterine devices, regardless of preference

A research team are seeking the answers to some fundamental questions about reproductive rights and choices in collaboration with people with learning disabilities.

We already know that throughout history people with learning disabilities have been told what to do and restricted when it comes to decisions about reproduction such as having sex, using contraception and having a baby.

Frameworks such as the Mental Capacity Act 2005 may be used to find out whether people can consent to sex and decide whether they want to have children or not.

We would like to know more about how these decisions are made and if or how this may be different to what is written down in the law and in policy.

We are concerned that there are some situations in sexual and reproductive healthcare that are making it hard for people with learning disabilities to decide if and when to get pregnant.

This can compromise reproductive rights. For example, there are cases where women with learning disabilities are encouraged to use methods of contraception that last for a long time (five years) when that is not their preference.

These types of contraception include the implant, which is placed under the skin in the upper arm, and intrauterine contraceptives (the coil), a device inserted into the uterus (womb).

Once you have these methods of contraception in place, it can then be difficult to get them removed when you want to have a baby, even more so at the moment because lots of sexual health services have closed and there are limited staff.

On the other hand, it may be hard for you to access contraception in the first place when you do want to use it.

To find out more, see the All Party Parliamentary Group on Sexual and Reproductive Health in the UK’s report Women’s Lives, Women’s Rights: Strengthening Access to Contraception Beyond the Pandemic (https://tinyurl.com/2dyrbuar).

Little information is available on how people with learning disabilities are supported to make decisions about contraception. While some people may benefit from additional support to do this or may have medical needs to consider, we are aware that there can be a fine line between having additional support and being pressured to take certain options.

We are interested in taking a reproductive justice approach to ensure the rights of people to make decisions about their own bodies are upheld and that assumptions about or discrimination towards people with learning disabilities do not unfairly influence the guidance that people receive about contraception.

Reproductive justice combines reproductive rights and social justice. You can find out more about it at https://www.sistersong.net/reproductive-justice.

Gaps in research

Research published last year by members of our research team in association with the British Pregnancy Advisory Service, Decolonising Contraception and Shine Aloud UK found many people felt pressured and discriminated against when it came to making decisions about their contraceptive method because, for example, of their age, ethnicity or sexual orientation.

However, for this report, we were unable to speak directly to many people with learning disabilities and learn about their experiences.

To address this gap, we have now received funding from an organisation called the Foundation for the Sociology of Health and Illness to explore in more detail what is meant by capacity to consent in relation to using long-acting contraception.

Consent, capacity and assumptions

We think it is important to understand how capacity and informed consent may be influenced by assumptions about the needs of people with learning disabilities as well as by the environment in which these decisions are made, such as during a short doctor’s appointment or after having a baby.

As part of this, we intend to work closely with people with learning disabilities to understand what matters most in relation to this topic and how we should do future research that is inclusive and aware of the needs of people with learning disabilities.

So far, we have been working to gather background information on this subject in the UK and identify what resources are available to people to support their rights to make decisions about contraception – which are few and far between.

To start this conversation with other people, in April this year we put on an event called Reprofest (https://reprofest.wixsite.com/reprofest) in Preston, Lancashire.

There can be a fine line between having additional support and being pressured to take certain options

This event brought together lots of people to talk about reproductive rights from a range of perspectives. At the heart of it all was our invitation to consider who makes decisions about who should have children and if or when someone should get pregnant.

Pictured is the Reprofest zine cover made by people at the event with local arts organisation the Good Things Collective.

We were joined at Reprofest by Inclusion North – a community interest company that “aims to make inclusion a reality for all people with a learning disability, autistic people and their families”.

Inclusion North’s experts by experience worked together to prepare workshops about reproductive rights for people with learning disabilities and/or autism to deliver at Reprofest.

It may be assumed that sex and reproduction are not a priority or are not appropriate topics to discuss with people with learning disabilities

They delivered two excellent, thought-provoking workshops based on their own questions and concerns they have about sex and reproduction. The contribution of Inclusion North has been very important so far in helping us consider priorities for people with learning disabilities.

We have learnt that questions about reproductive rights, contraception and if or when you get pregnant are hindered because of silence around sex.

Many professionals such as doctors, nurses or support workers find discussing this awkward and sexual and reproductive health are often missed out of annual health checks.

They may also assume that sex and reproduction are not a priority or appropriate topics to discuss with people with learning disabilities, so this topic is swept under the carpet and overlooked.

We know that having a learning disability is only one aspect of a person. Other parts of who we are may also be judged and make it harder to explore options related to sex and reproduction – for example, if you have a learning disability and also are an LGBTQ+ person.

Uncertainty about what may happen if you want to get pregnant and have a baby can create fear. For people with learning disabilities, worries about being judged as not being able to look after children may increase this fear.

Being frightened can make conversations about your needs even harder to have and may mean you end up agreeing to things other people think are best for you.

How these factors influence people’s lives and affect their ability to give informed consent are important to understand.

We think it would be helpful to develop training and resources with people with learning disabilities to support them to make decisions about contraception and reproduction.

We are aware we do not have all the information we need to do this work in the best way. If you are an organisation or individual and would like to help us pull back the carpet under which the conversations about sex, reproduction and contraception for people with learning disabilities are often swept, you can contact me at the email below.

We hope to form partnerships with organisations that support people with learning disabilities.

We hope that this project will go some way to shining a light on capacity and informed consent, especially about contraception, in a way that is inclusive and understanding of people with learning disabilities.

We want to work towards a reality where reproductive rights can be upheld for everyone and that the diversity of people’s needs and ways of supporting them are understood.

The authors would like to thank the hard work of the experts at Inclusion North for their enthusiasm and commitment to this topic

Rachael Eastham is senior research associate in the Division of Health Research at Lancaster University: r.eastham1@lancaster.ac.uk. The rest of the research team are: Alex Kaley, Mark Limmer and Sophie Patterson at Lancaster University; Gareth Thomas at Cardiff University; and Victoria Boydell at the University of Essex.

https://www.goodthingscollective.co.uk; Saramikr/Wikimedia Commons CC BY 4.0