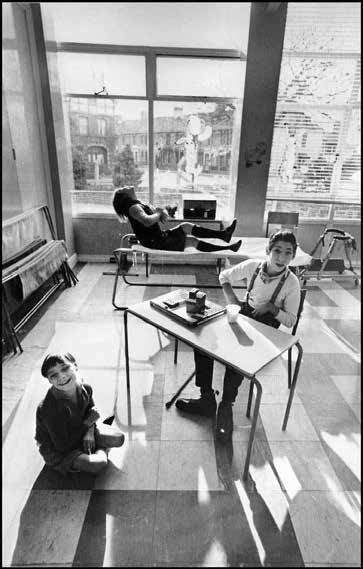

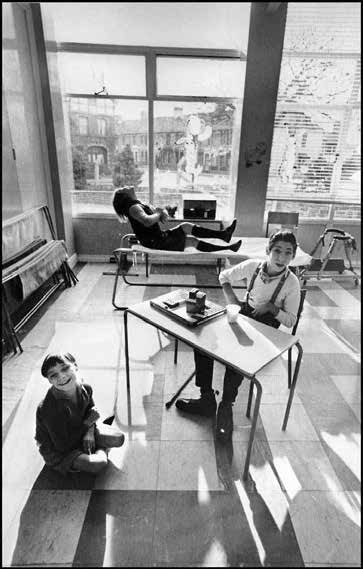

Children at Ely Hospital: sedatives were used excessively to control behaviour, the inquiry found

In August 1967, a story broke in the News of the World. It concerned Ely Hospital in Cardiff, an NHS long-stay institution housing around 600 patients, some of whom had lived there for over 50 years, and most of whom were classed as “sub-normal” or “severely sub-normal”.

The source of the story was Michael Pantelides, a Cypriot-born nursing assistant who worked there. He painted a picture of a hospital where an absence of strong leadership and a corresponding policy of cover-up among senior staff had fostered an environment where certain members of staff regularly stole from patients and imposed their authority with physical violence including restraint and threatening, bullying behaviour.

Following these revelations and the accompanying public outrage, a government inquiry chaired by Geoffrey Howe QC (later to become a senior minister in Margaret Thatcher’s government) was established by the Welsh Hospital Board at the request of minister for health Kenneth Robinson.

Over the next two years, the committee gathered more than 1,000 pages of evidence from staff, patients and parents, made site visits and examined case notes, ward books and other documents from the hospital.

In March 1969, following a political tussle over publication that was settled only by prime minister Harold Wilson’s intervention, the inquiry’s report was published in full.

‘Rough’ nursing

The inquiry found that most of the alleged incidents of ill treatment reported in the News of the World article had indeed taken place.

Although it was frequently impossible to establish intent, the inquiry held that at the very least there was a “persistence of nursing methods which were old fashioned, untutored, rough and, on some occasions, lacking in sympathy”.

The widespread consumption by staff of food (particularly meat) that had been provided for the patients was also confirmed, and the case referred to the director of public prosecutions.

The inquiry’s investigations uncovered further abuses, including in the villa for boys. Parents complained that they had found their children dehydrated and filthy, bored and neglected with no stimulation or access to toys. The excessive use of sedatives to control any challenging behaviour was also reported.

Throughout the hospital, staff felt it was useless or even dangerous to complain about conditions or colleagues’ behaviour. Some had found themselves forced to leave while the perpetrators were left in post, free to continue their abusive practices unpunished.

Public outcry sparks change

Following the inquiry’s publication, there was further public outcry and significant changes were made. At Ely Hospital, these included increases in both staff (including the reinstatement of those who had complained and been dismissed) and funding, and the replacement and reorganisation of the hospital’s management committee.

Significantly, Howe had insisted that the inquiry had a wide brief, and should look beyond Ely to assess how learning-disabled patients were being treated in the NHS as a whole.

There was an acknowledgement that abusive behaviour had been allowed to flourish in some corners of Ely Hospital owing to its isolation from both the community and from other institutions, and that this had happened in part because of a lack of external overview.

As a result, Robinson’s successor Richard Crossman established the Hospital Advisory Service to regularly visit and report back on the condition of hospitals, particularly long-stay institutions such as Ely.

This was followed in 1971 by the Better Services for the Mentally Handicapped white paper, which recommended closing long-stay hospitals and housing patients in the community. This policy would result in the eventual closure of Ely Hospital in 1996.

People tell their stories

The inquiry’s report noted there had been attempts to interview many of the patients mentioned in the News of the World article, but, “because of the severe disabilities of most of them, little assistance was derived from this source”.

In 2014-2017, an oral history project both challenged this claim and sought to rectify the situation. The Hidden Now Heard project set about capturing stories, images and objects from the residents and staff of Wales’s six old long-stay hospitals, among them Ely. By doing so, they hoped to ensure that “history is told and not forgotten”.

Ely Hospital was the first major hospital scandal following the Second World War, but it was to be the first of many.

Further reading

Drakeford M. Why the Ely inquiry changed healthcare forever. Wales Online. 6 February 2012. https://tinyurl.com/n95c9tn4

Hunt P. Hidden Now Heard – Unearthing Stories. Learning Disability Wales. 8 August 2018. https://tinyurl.com/dfwkytjx

Hutchinson C. Ely Hospital (various articles). Wales Online. 2012-2015. https://tinyurl.com/5avtpsnw

Ely Hospital: Hidden Now Heard. https://www.peoplescollection.wales/collections/579951

Ely Hospital Remembered. Channel 4 News. March 2016. https://tinyurl.com/59v8d53j

Report of the Committee of Inquiry into Allegations of Ill-treatment of Patients and Other Irregularities at the Ely Hospital, Cardiff. CM 3975. 1969. https://tinyurl.com/4bcfh3wa