Leo Andrade was joined by hundreds of people to protest over how people with learning disabilities were being treated in assessment and treatment units. Seán Kelly interviewed her

We should strip naked and chain ourselves to the railings at Westminster.” Leo Andrade was talking to a friend who, like her, was a mother of an adult detained in an assessment and treatment unit (ATU).

Both felt stripped of their voices and also that their children had been stripped of their rights. The question was how to bring the issue to public attention.

The friend said she would chain herself at Westminster but, not unreasonably, she drew the line at being naked. Eventually, another friend persuaded Andrade that she would be in danger of being arrested and locked up. Not a great situation for a single mother of three children.

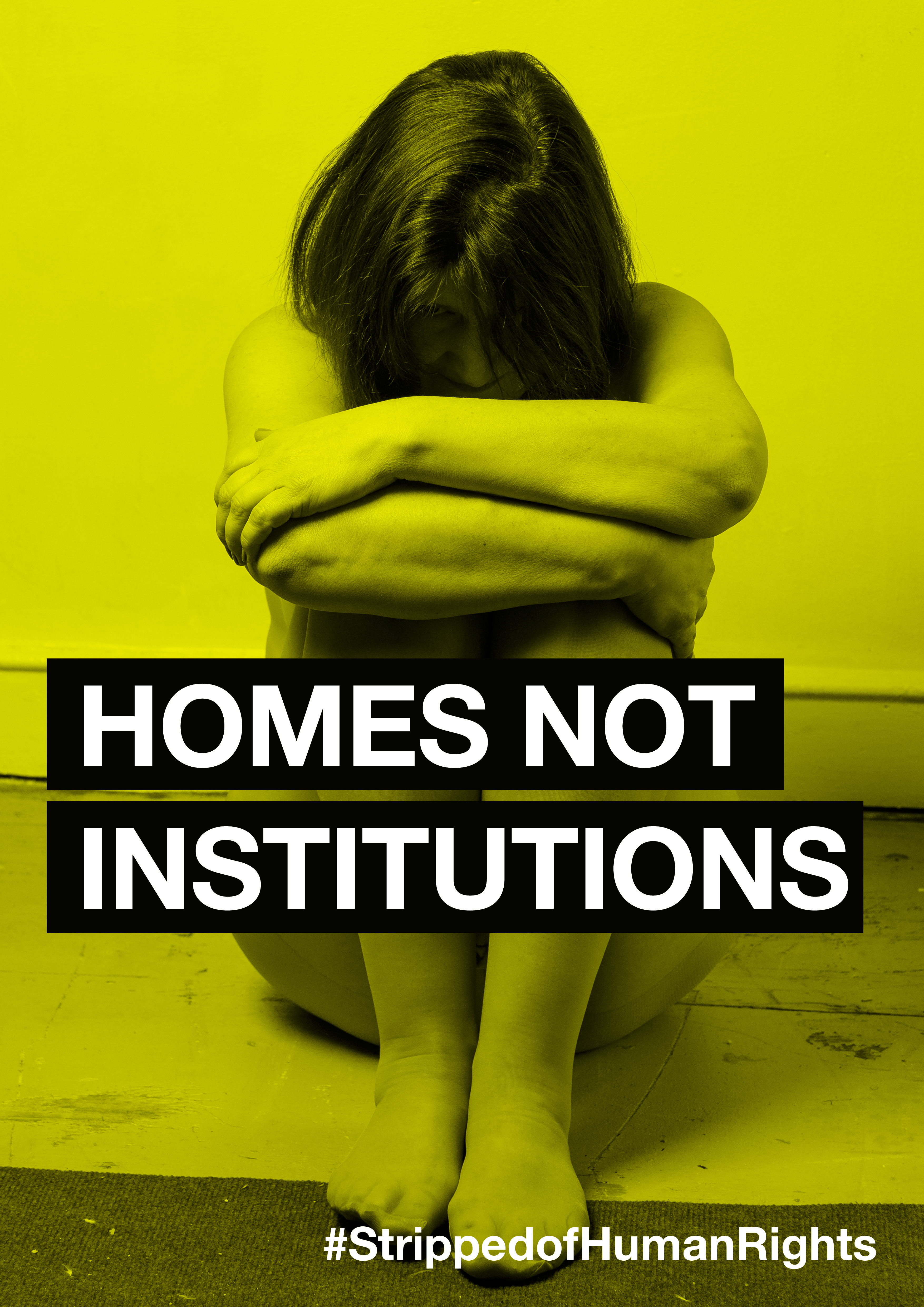

So Andrade developed the idea of a week of protests using posters which showed her metaphorically “stripped” of her voice and her rights. I first met her after being asked to take the photos. My wife Mary came with me to Andrade’s house and, together, the three of us made photos of her being physically restrained, looking frightened and with a hand or tape across her mouth.

Designer Henry Iles then did some great work to turn them into posters and fliers and Alicia Wood, the co-founder of Learning Disability England, added some strong text. As Andrade says, the results were powerful.

Recently, I met her again to reflect on the campaign and to hear more about her son Stephen and his life in ATUs.

Andrade describes the years Stephen spent at St Andrew’s Hospital and later at the Priory. No one would deny that Stephen needs care and support.

Andrade says he is autistic with mild learning disabilities. He has limited speech but he can read and he has a very funny sense of humour, she says, along with “a gorgeous smile with dimples”.

However, he does sometimes harm himself by banging his head onto hard surfaces, which can be difficult to deal with.

At one point, her local authority was paying £14,000 a week to the ATU for three-to-one support for him. Despite this, he suffered numerous injuries and visits to hospital A&E departments.

At home, Stephen liked to have a shower every morning and a bath at night to settle him before bed. At St Andrew’s, this didn’t happen as it was not part of the institutional regime. However, in Andrade’s opinion, he had not had a bath or shower for six months. She says his hair was matted, his underwear was stuck to him and he smelled terrible.

When she asked staff about it, they said that they were not allowed to touch Stephen or lead him to the bath. They said Andrade could not give him a shower as she was not insured.

So she took matters into her own hands. On the next visit, she and her then husband brought large water containers. After paying £2 to the café in the grounds for heated water, they hung a sheet from a tree to create a private space and gave Stephen an outdoor shower. She says: “He was shivering. But you should have seen the happiness of that young man.”

She is still angry. “They call this a hospital? It is worse than a prison. Even prisoners have rights – they get showers.”

Finding others

Andrade was in despair. With help from a friend, she contacted Dan Scorer at Mencap. Scorer listened to her and enabled her to join a Mencap parents’ group set up after the Winterbourne View scandal.

She says the support was crucial to her own wellbeing. “I can categorically say now that Dan saved my life,” she reflects.

By the time Stephen was at the Priory, he was on eight antipsychotics. Andrade says at this point his tongue was swollen and he no longer spoke at all. On one visit, he just managed to walk over and sit next to her before falling asleep.

He continued to self-harm despite the high level of supervision he was meant to have. On one occasion, he hit his head on a hard surface, causing a gash from forehead to scalp that needed 80 stitches. It seems he was also injured by others. His arm, wrist and fingers were all broken.

Andrade says that, in addition to the medication, he was sometimes kept in a straitjacket all day. Staff said the straitjacket was better than being in complete isolation.

One day, on a visit at the Priory, Stephen took her to the toilet and showed her serious injuries in between his legs.

Andrade says that, within the bruised and bloody damage, she could clearly see what appeared to her to be the print of a boot.

“I felt that Stephen was going to die. My son is coming home in a box,” she says.

However, she was unable to get him discharged. She says that discharge dates were promised but they came and went. With the help of friends, she kept fighting for Stephen’s release.

Mencap helped her to take Stephen’s story to the local paper and onto radio and TV. She met MPs and eventually spoke with three successive ministers with responsibility for health and social care

– Sir Norman Lamb, Alastair Burt and Matt Hancock. She says that Lamb really helped to move things on for Stephen.

When she asked Burt if he would continue that work, he said he could not issue instructions to local authorities. “Then what the fuck is the point of having a minister?” she asked. Apparently, he told her that was “a good question”.

One day Andrade was contacted by staff who said Stephen had a lump on his chest. It turned out that his collarbone had been fractured in three places.

Andrade says staff sent her to the wrong A&E department while Stephen was being x-rayed elsewhere at a private hospital.

Hours later, Stephen was brought to the general hospital. The consultant was concerned because he said such an injury was usually caused by a car crash or falling downstairs.

Stephen had not been in a car and there were no stairs. Therefore, the consultant said, it must have been some other excessive force. He also said the injury had happened almost two weeks earlier than staff had noticed it.

Andrade reported all this to the police. She says the police reviewed CCTV tapes and saw Stephen being restrained with significant force and being thrown across a room, either of which could have caused the injury.

When interviewed by police, one staff member accepted that he might have caused the injury while restraining Stephen. Andrade says this employee was actually one of the best and that she understood the difficulties they experienced including being understaffed, undertrained and underpaid. She eventually wrote a letter to the man forgiving him.

By then, Stephen had moved to a community setting. Andrade is thankful Stephen survived. “He could have been one of the statistics,” she reflects.

Andrade knew that she had to campaign for an end to the ATUs as “all my friends were going through this too”.

Her campaign was called #Stripped of Human Rights. The plan was to protest outside NHS England’s offices in Victoria Street and at the NHS England headquarters at Elephant and Castle, both in London.

On social media, the plans grew and people across the country joined in.

Andrade says that more than 1,200 people

came to protest in London. In Newcastle, 500 people demonstrated. In Birmingham, the protest was supported by the local Mencap and attended by 200 people.

But the impact on policy was disappointing. Andrade received a letter from NHS chief executive Simon Stevens via Ray James, his national learning disability director, but says it was just

a courtesy. “It told us nothing that we didn’t know,” she says.

As for Stephen, he is much happier living in a community service. Andrade says: “He has good people with him now. They like Stephen. I can see care and respect.” It is the very least someone should have.

In the future, Andrade hopes to get Stephen home properly. And she has not given up protesting. She has gone back to the idea of chaining herself up – this will happen next year at an ATU. After all, she says: “They need a rude awakening.”

Seán Kelly was chief executive of the Elfrida Society from 2001 to 2012 and is now a writer and photographer