IQ testing caused widescale anxiety that the US population was rapidly losing its intellectual powers after 1.75 million soldiers achieved alarming scores. A century later, the consequences are still being felt, says Simon Jarrett

The IQ test was invented by early French psychologist Alfred Binet. His 1908 test is the prototype for those used today.

In the 1890s, Binet had tried to define intelligence by measuring and comparing the skull sizes of clever and not-so-clever people. He abandoned this approach when the skulls of “idiots and imbeciles” turned out sometimes to be larger and of better quality than those of people deemed highly intelligent.

His tests, commissioned by the French education ministry, were designed to identify children in normal classrooms who were struggling and might need special education. A series of short tasks and questions were used to identify a child’s mental age, which was compared to their actual age.

Binet had intended his test as a general indication of a child’s progress, rather than as some sort of irrefutable science.

However, his idea was taken up and used for different purposes. The idea of an exact intelligence quotient was invented, scored by dividing mental age by chronological age.

Psychologists proposed that intelligence was a precise, measurable attribute that could be measured accurately across all people and all cultures. This would support their claim that psychology – derided by many as a mixture of philosophy and wishful thinking – was an exact science, like physics.

Furthermore, in line with eugenics theory, they claimed this thing called intelligence was inherited, and not influenced by environment or education.

‘Moron’ mayor

IQ (intelligence quotient) testing was taken up enthusiastically in the US. Early versions had already produced some interesting results – in 1915 the mayor of Chicago tested as a “moron” (the newly invented term for a “feeble minded” person) on one version of the Binet scales.

In 1917, Harvard psychologist Robert M Yerkes decided that the world war, which involved the mass mobilisation of soldiers into the US army, presented an unmissable opportunity to demonstrate the IQ test’s scientific validity.

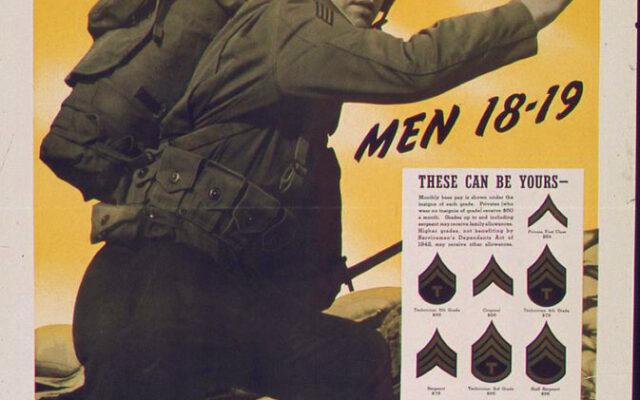

Drafted into the army as a colonel, he presided over the administration of mental tests to 1.75 million men, something he called a feat of “human engineering”. Tests were administered in written form for the literate and in pictorial form for those who could not read. They were timed and often taken simultaneously by large numbers of men under the supervision of an examiner in specially commissioned buildings.

The results came as something of a shock. According to the data, the average white American had a mental age of 13. This stood just marginally above the designated mental age for a moron, which was between eight and 12. Furthermore, the results suggested that 37% of white Americans and 89% of “negroes” fell within this category.

This all took some explaining. It confirmed many of the racial and class prejudices of Yerkes and his fellow psychologists, who were all hereditarians, believing that intelligence or a lack of it was inherited and lowest among non-whites and the poor of all races.

However, the sheer scale of it seemed to suggest the whole country was rapidly degenerating, with even the white race – God forbid – heading for mental oblivion.

Convoluted and racist explanations were produced. For example, many of the whites were recent immigrants from southern Europe, Jews or eastern Europeans of “lower stock” than western and northern Europeans. The “negro” results simply confirmed existing racist assumptions.

There were calls for curbs on immigration and admission of refugees to prevent the “moronisation” of the country. These calls resonated during the 1930s Jewish refugee crisis caused by Nazism, and persist today.

Debunked – but myths live on

In his brilliant book The Mismeasure of Man, Stephen Jay Gould dismantles and invalidates the whole Yerkes testing programme. The tests were deeply culturally biased, inefficiently administered, methodologically incompetent and had no scientific merit.

He describes the testing as “a shambles, if not a disgrace” (Gould, 1996: 231). No credence had been given to any possible educational or environmental factors. Educated northern black soldiers far outscored their southern counterparts, who had been allowed no education – this was quietly ignored. Recent European immigrants with poor English struggled to answer questions such as “Crisco is a: patent medicine/disinfectant/toothpaste/food product” – questions that were culturally and linguistically incomprehensible to them.

Yet the findings lodged in the American political and public consciousness, stoking fears about the feeble minded, race and foreignness.

To this day, we persist in the belief that we can precisely measure a thing we call intelligence. If you score 70 you have a learning disability – if you score 71 you do not. Psychologists continue to patrol the boundaries of human belonging, pronouncing who is in and who is out – thanks to the flawed legacy of men like Binet and Yerkes. n

Gould SJ (1996) The Mismeasure of Man. New York: Norton