At the start of a recent emergency department shift, Dr Liz Herrieven overheard a colleague using plain, clear and jargon-free language to explain the use of a cannula to a patient.

Aware the patient had a learning disability, the doctor had also found a quiet area for the consultation, and ensured the patient’s carer was present for reassurance.

This approach was thanks to the Learning Disabilities Toolkit, written by Herrieven, a consultant in emergency medicine at Sheffield Children’s Hospital, and recently published by the Royal College of Emergency Medicine.

It is the first toolkit of its kind for emergency medicine, aiming to ease health inequalities by supporting doctors to treat learning disabled people more appropriately.

A toolkit exists for hospitals but there is none specifically for emergency departments.

No training for doctors

Herrieven, parent to a teenage daughter who has Down syndrome and is autistic, says: “Patients with a learning disability face huge barriers to healthcare resulting in significant health inequalities but, as doctors and nurses, we’re taught very little about how to improve care. There’s nothing in postgraduate training for emergency doctors about learning disability and very little in undergraduate training.”

In the toolkit’s introduction, Sara Ryan, professor of social care at Manchester Metropolitan University, describes its “potential to transform the emergency healthcare of people with learning disabilities”.

Specific difficulties for these patients include long waiting times, noise and the fact that admission is sudden, without time to prepare.

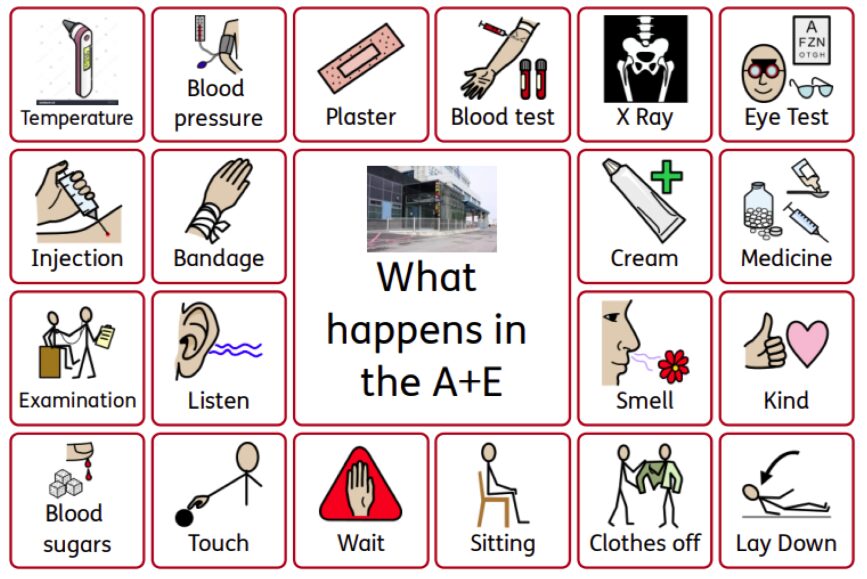

The toolkit offers downloadable resources, plus information on reasonable adjustments such as offering ear defenders to help with auditory sensory overload. Clinicians are encouraged to support verbal communication with visual aids such as symbols, and to regard family and carers as “a valuable source of information”.

The resource explains diagnostic overshadowing – when a clinician attributes symptoms to a condition the patient is known to have – and stresses how this is responsible for missed or delayed diagnoses in patients with a learning disability and those who are autistic.

It suggests quiet areas for those with sensory processing difficulties and sharing images of the department online, so people can familiarise themselves.

Herrieven, a member of the steering group for a network of doctors (the Down Syndrome Medical Interest Group) and a Down’s Syndrome Association health adviser, says her daughter’s life-threatening illnesses gave her insight into what it is like being a parent to a seriously ill child.

Amy spent her first few months in neonatal intensive care. She was later in high dependency and intensive care units with illnesses including severe chest infections, pneumonia and sepsis.

Herrieven says a specific resource is more critical for emergency medicine than other healthcare areas such as GP surgeries or outpatients.

This is because of the high volume of patients with a wide range of urgent problems, which doctors have to diagnose and treat as well as identify quickly those who are critically unwell.

“This is even more difficult if our patient has a learning disability, as there may be communication differences, we may need to take more time, there may be an increased risk of certain illnesses and our patient may need support tolerating or understanding procedures, for example.”

Herrieven believes raising awareness is vital to improving outcomes. She adds that, while awareness seems to be growing, especially since the 2022 launch of the Oliver McGowan Mandatory Training on Learning Disability and Autism – this is recommended by the government for health and social care staff – “there’s a huge amount still to do”.

She says of the toolkit: “I hope it can improve care for at least one person out there. On a bigger scale, if it can raise awareness of the issues among emergency department staff then we can start to hope for better care and outcomes for all patients with a learning disability.”

The toolkit (PDF) is free to download from the Royal College of Emergency Medicine website.