Lockdown was an opportunity to revive a long-neglected oral archive from the late 1980s, and bring to light the first-hand testimony of an asylum’s former residents and staff.

It also seems very timely, as contributors to Community Living have been lamenting the regressive steps they have seen back towards institutional “care”. The lessons of the past should not be forgotten.

When the purpose of the Royal Western Counties Institution, Starcross Hospital, a former “idiot asylum” in Devon, started to be seriously questioned, it had existed for more than a century. Hundreds of people had lived out their lives there in a separate, regimented world.

What followed was the first closure of a large “mental handicap” hospital in favour of a range of new community care services.

Health authority manager David King asked for an oral archive to be created before the memories of Starcross Hospital faded. Staff and residents were interviewed and what they said was recorded and transcribed.

King went on to head the national Mental Health Task Force and wrote a book on how the transition to community care was achieved (King, 1991). He foresaw a day – correctly, it now appears – when the realities of institutions might be forgotten.

King, who later headed health services in New Zealand, has contributed a commentary to the now-published archive extracts.

He writes: “Institutions like Starcross Hospital harmed human life and must never be repeated.”

His is a voice that should resonate loudly. He questions how it took so long to end institutional care.

The idea to close the hospital had come from within not above, yet even those with a vision for better care and the determination to succeed were emotionally torn, as the archive reveals.

Speaking soon after the closure, nursing officer Viv McAvoy, who was heading a new local support service, recalled: “In some ways I felt quite sad and, again, I felt quite glad. The whole thing is a conflict of emotions and still is.”

The interview extracts also shine a light on the circumstances that led to people being admitted and then living out their lives at Starcross Hospital. In many cases, staff lived out their working lives there too – even their own holidays were spent with the people in their care.

Nursing tutor Tom Bush said: “People said they would never close it – it has been a wonderful place. But I think they were very much living with a dream an old idea old memories If you talk to the new staff coming in, the youngsters would say: ‘Oh, it’s too big, it’s so impersonal’.”

Reading what the interviewees said, it is possible to appreciate that staff did their best within the very limiting confines of an institution.

Updating the buildings drained resources while doing nothing to alter the fact that this was a life apart from the rest of society for those who lived there.

Meanwhile, by the 1980s, the majority of people with learning disabilities or special needs were living with their families or trying to fend for themselves.

What the contributors said about the pride staff took in their work, the institutionalisation of those who lived and worked there and the perceived inadequacies of the early efforts to move patients into the community all help to explain why the status quo endured for so long.

Caution over independence

Finding homes for supported living can be difficult. Lisa Brown is bringing property investors and care providers together to design and create accommodation to meet various needs.

There was also a deeply ingrained belief that the patients could not learn or adapt. Medical superintendent Dr David Prentice explained: “We were always bedevilled by this feeling of permanence that there was no way out for them ever standing on their own feet.”

However, staff discovered otherwise.

As King put it: “Although hospital care was supposed to be beneficial, release from hospital has been as good as a cure for so many who were thought to be beyond hope.”

The testimony in the interviews suggests that Starcross might not have been necessarily representative of large asylums in general and, perhaps, suffered from fewer of their most regrettable traits.

Nevertheless, it limited people’s lives. It was a big employer in the village of Starcross – a village within a village you could say, but a place apart.

The philanthropy of the past had created the institution to provide a purpose in life but, in reality, “purpose” had dwindled to patients sitting on the boundary wall, looking out on a world denied them. They had no personal possessions, and no choice over the food put in front of them or the activities they could take part in.

For some, as the interviews reveal, institutional life had advantages: shielding them from an unkind or difficult world; a routine; friends close at hand; and even daily GP care.

But in many ways the ease of life was an illusion. There were plenty of downsides, not least being constantly in a crowd of people and having no sense of your own family in what was often a hothouse for antisocial behaviour.

Nursing officer Sheila Easby was at the heart of early attempts to move care into the community: “Originally, the groups that went into small hostels thought they were going into a different sort of institution but, at that time, it was better than the institution they came from.”

In praise of privacy

Finding homes for supported living can be difficult. Lisa Brown is bringing property investors and care providers together to design and create accommodation to meet various needs.

She recalled: “I remember one resident she added: ‘One of the nice things about being out, I can go to the bathroom and I can lock the door I haven’t been able to do that before’.”

This was echoed by McAvoy: “The two awful things about the institutions was the total lack of privacy and the lack of choice, particularly in terms of diet and when they actually ate.”

“They were environmentally handicapped – by the environment around them,” recalled nursing sister Jean Waldron, who had taken the leap from running a crowded hospital ward to overseeing a new local unit providing support and respite care.

“Some of them had been in hospital care since they were in their early teens and they were in their 80s now and had never had a bedroom of their own. Unbelievable!

“When you are elderly, you usually have problems with your waterworks… they literally had to go about 50 yards to get to the nearest loo and, to me, that was absolutely atrocious.”

Institutionalisation had a lot to answer for. Psychologist Dr Chris Williams explained at the time: “Behaviour problems – they are not constitutional problems of mentally handicapped people, they are situational problems. When they have to compete with 30 other people then you hit your head somewhere and you find out how that works and you do it again.”

Staff and some residents saw the hospital through the lens of familiarity and liked to recall the happy side of life there – and that also helps to explain why the institution persisted for so long,

Having decided that closure was the best and only viable option, the challenge was to visualise what could be provided instead. The vision of that time is a useful measuring stick for what passes for community care now, decades later.

To have your own room, your own front door, the chance to choose and not be closed off from the world – all these should be rights. Equally, support should be available to make these possible. Life in the community should not mean stress and uncertainty, loneliness and empty days.

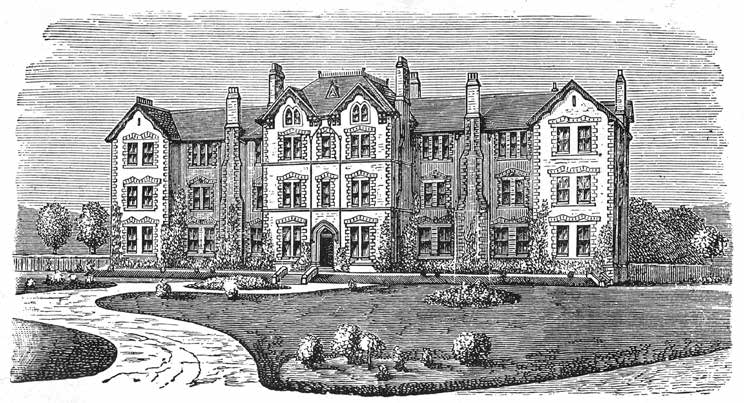

The institution opened as the Western Counties Idiot Asylum in Starcross, Devon, in 1864 – the picture above is from 1876. In 1914, it became the Western Counties Institution, Starcross. In 1948, it was transferred to the NHS. It finally closed in 1986, in line with government policy on closing institutions and a move to care in the community.

The difference outside

Finding homes for supported living can be difficult. Lisa Brown is bringing property investors and care providers together to design and create accommodation to meet various needs.

The oral archive interviews reveal some key points that arose from the closure and the move to care in the community perceived by people involved at the time.

McAvoy pointed out: “The things that are better are the attitudes of the new staff, who have never probably set foot inside an institution. It’s lovely – they do look upon people with disabilities as equals and they treat them like that naturally. That is absolutely superb.”

Easby said: “The local support units… so that you were still near your family … book yourself in and out,” but added: “One thing about community care, you do need procedures and you need monitoring systems.”

Regarding respite, Waldron said: “Compared to. Starcross the unchanging routine there’s a tremendous difference. They go and sit and have coffee and chat to people, parents are in and out, a busy little unit.”

However, she warned: “You get some parents who will abuse the system and there are some who will only use it in a dire emergency… and I’ll say ‘It’s time he came in, I expect you need a break?’ If there isn’t short-term care for young people, the family aren’t going to cope.”

Perhaps Williams should have the last word: “I think it’s an important thing to realise that people didn’t ask to come back.

“It was said at a Starcross meeting, by a patient on the team: ‘Why can’t I live in a house like everybody else?’ And it’s when you try to answer that question It was Ken, who now lives in his own house in Plymouth.

“It exposes the bizarre fact that we were in the guise of treatment and hospital care. Looking back, we ask: How could we do those incredible things?”

Caroline Hill is a former NHS head of communications. She was asked to create the Starcross oral archive which is at https://starcrosshistory.blogspot.com/

Read the stories from the Starcross archive

Finding homes for supported living can be difficult. Lisa Brown is bringing property investors and care providers together to design and create accommodation to meet various needs.

The doors of Starcross Hospital closed in 1986. Fast forward 34 years to a document box, opened in the first lockdown of the pandemic.

As I read through the contents, the voices of nearly 40 people, talking decades previously, come back to life – I could hear some of these voices in my head as I had recorded many of the interviews and listened to a number several times while typing up the original transcripts.

All had lived or worked at Starcross Hospital and had agreed to share their thoughts and memories at the time of its closure. The archive contains colourful memories stretching back to the 1930s of life in and around the imposing Victorian building and how the closure came about.

Residents and staff have at last been honoured in a compilation of interview highlights I have edited. Starcross Hospital: What the Voices Tell Us is freely available at: https://tinyurl.com/6tehvys6