A Fit Person to be Removed: Personal Accounts of Life in a Mental Deficiency Institution was the result of a three-year project interviewing eight men and nine women who had spent most of their lives in Meanwood Park Hospital (the Park) near Leeds, a long-stay institution established as a “mentaldeficiency colony” in 1920.

The authors, clinical psychologist Maggie Potts and researcher Rebecca Fido, believed that academic studies of learning disability had until then been preoccupied with institutions and legislation, meaning that the erstwhile residents of these places were being excluded from their own histories when they had valuable contributions to make and a desire to share their experiences.

The closure of long-stay hospitals, including the Park, gave an added impetus to gather the oral histories of its residents while this was still possible. These reminiscences form the basis of A Fit Person to be Removed, a study that sought to contribute to the history of the Park through the memories and experiences of its residents.

Those who contributed had spent between 25 and 63 years there – on average 47 years. Five of the group were described as having “severe physical handicaps”, and three required interpretive help from friends during the interviews.

Through their recollections, an alternative history of the Park unfolds. It reveals the arbitrary and callous reality of the certification process that brought 16 of them to the institution then prevented them from leaving. Reasons for certification ranged from social transgression (having a child out of wedlock) to communication skills (especially for those with physical disabilities) to displaying a lack of general knowledge. Those whose families could not support them because of the death of a carer or financial hardship were also more likely to find themselves going through the certification process.

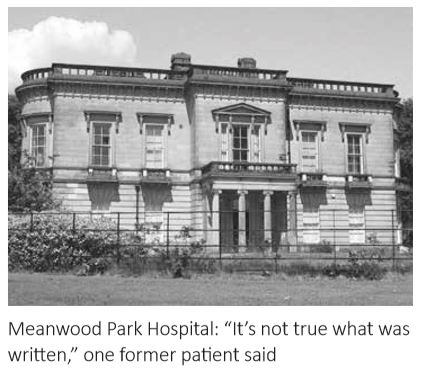

The reality of their experience stands in contrast to the narrative of the official documents. Through their testimony, the boredom and loneliness of those branded “lower grade” and largely confined to their “villa” (ward) were laid bare, as well as the injustice felt at the strict segregation of the sexes.

Reality and the rat-catcher

The contrast is highlighted between the official guidance that staff should build trust with patients and parents and the reality that, for instance, the executive officer who rounded up likely candidates for certification was widely feared and referred to as “the rat-catcher”.

The annual reports also boasted of the many entertainments available at the Park, but did not record that the showing of films on site actually curtailed the independence of the more trusted residents, preventing them from going off site to the local cinema, nor that the films selected were often old and unpopular, nor that some of the more physically disabled residents were left out of these entertainments altogether.

More disturbingly, the annual reports did not say the withdrawal of these entertainments was part of a punishment system that included withholding money and leave, hard physical labour in humiliating conditions, beatings, prolonged solitary confinement and medication with laxatives or sedatives.

Some of these strictures were presented as inducements to favourable conduct but were part of an arbitrary informal system of punishment that contributors revealed could be meted out for anything from swearing to incontinence to feeling too depressed to eat.

Taken seriously at last

As the book progressed, Potts and Fido shared regular readings of their work with the contributors.

The whole process of being listened to and having what they had to say taken seriously proved cathartic and empowering for the interviewees, with some expressing greater emotion as the interviews and readings went on, and increasing confidence in the importance of sharing their stories. Although at times these memories provoked distress, there was a sense that: “I just like people to know so they can realise what it was we’ve had to go through. It’s not true what was written down! They did it just to keep us locked up, so that people would think we’re mental!” (page 139).

From the authors’ point of view, the exercise emphasised not only the importance of hearing about institutional life from those who had actually lived it, but also the necessity of using their testimony to shape the future.

Written at a time of huge change in the care system, A Fit Person to Be Removed showed what life was like in the Park – and, indeed, after the Park – for these individuals, with both good experiences and bad. and stressed the need to acknowledge the continuities in systems and attitudes rather than just dismissing them as belonging to another era. By doing so, they hoped to avoid the mistakes of the past.

Further reading

Meanwood Park. Digital archive. www. meanwoodpark.co.uk Fido R, Potts M (1989) “It’s not true what was written down!” Experiences of life in a mental handicap institution. Oral History. 17(2):31-34 Potts M, Fido R (1991) “A Fit Person to be Removed”: Personal Accounts of Life in a Mental Deficiency Institution. Plymouth: Northcote House Publishers