My son James was diagnosed with autism when he was three.

We received the news a few days after Christmas 2009, but it wasn’t much of a surprise: in the months beforehand, he had been repeatedly visited, observed and developmentally tested to the point that the whole family had started to reach its limit.

I had watched him being told to push coins into money boxes, pick up tiny beads and build towers of bricks, registering what was obviously a series of fails.

There had been strange and seemingly pointless questions: “Does your child eat very quickly? Can your child kick a ball that isn’t moving?”

Cold experts

And, even after he received his diagnosis, the dour, cold, sometimes bizarre tone of our encounters with experts and professionals continued.

When he was four, for example, we got yet another report from an NHS paediatrician that baldly laid out some of what James’s autism and learning disabilities meant: one of the more cheerful passages said that “James showed fleeting eye contact with me but it was of abnormal length and devoid of social meaning … James has poor reciprocal social interaction and poor speech which is certainly not fluent.”

That hurt but, by then, we had developed much thicker skins than I ever thought we would.

Fourteen years later, I have just completed a book about James’s life so far, and the world of fascination it has long since opened up.

Maybe I’m Amazed is the story of how all four of us – James, me, my partner Ginny and our daughter Rosa – eventually emerged from the black cloud that had been placed above us as we realised that he was every bit as complicated, creative, funny and fantastically human as anyone else.

And it explores what sits at the heart of so many of our shared experiences: the deep and overlooked connection between autism – and learning disabilities – and music.

When he was two, James taught himself how to use my iPod. He was already obsessively listening to songs by The Beatles, and memorising all the words and music. Later, he would develop similarly devoted interests in Kraftwerk, The Clash, Funkadelic, Amy Winehouse and many more bands and singers besides, and learn to play keyboard instruments, as well as the bass guitar.

We eventually discovered that, like many autistic people, he had what musicologists call absolute pitch: the ability to name musical notes as soon as he heard them and follow music as a matter of instinct, which is one part of an even bigger talent for hearing things in songs and pieces that most people would either ignore or miss. These things have been massively important to his experience of education.

Like so many parents, we had to fight to get the kind of intensive one-to-one support James needed in the mainstream. We live in Somerset, where there are still middle schools – and it was at that stage of his schooling that what professionals call “inclusion” really worked. Some of this was down to a welcoming, endlessly curious music teacher who ensured James played music in school productions – three times – and had the run of a room full of instruments.

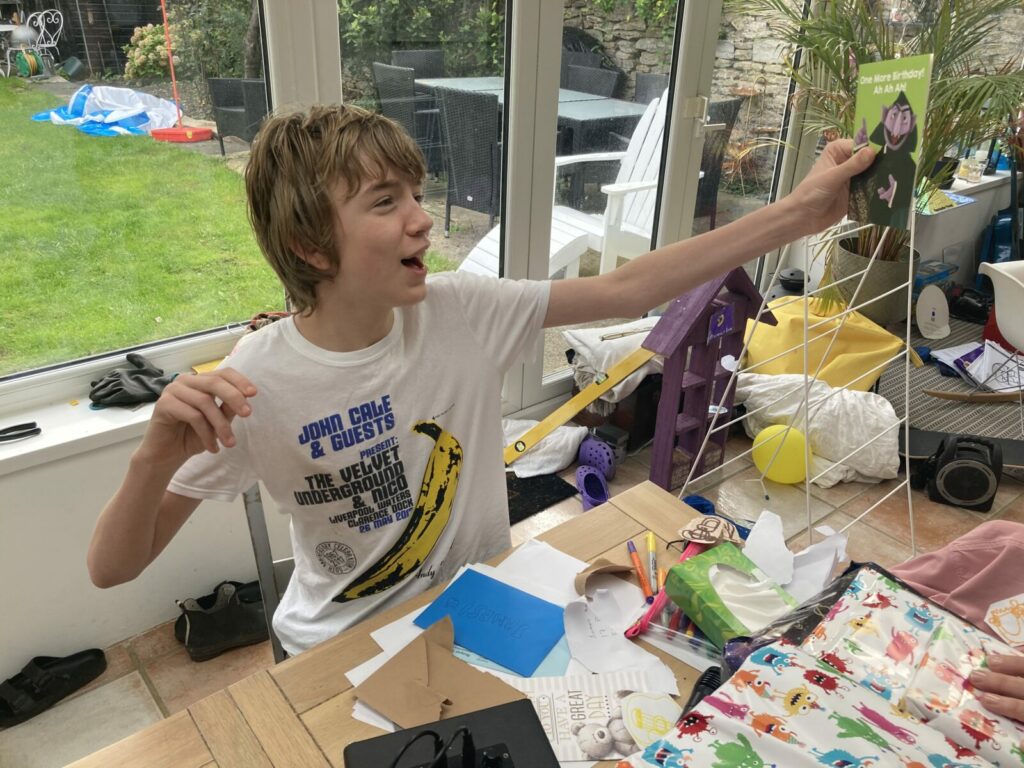

The high point was the night the two of us (him on vocals and keyboards, me on guitar) played The Velvet Underground’s I’m Waiting For The Man at a midweek concert to a packed hall: the feeling we got was the precise opposite of the cold, limiting messages we’d been given when James was diagnosed.

He went from that school to an autism specialist setting, where his best experiences continued to involve music: regular music therapy sessions, lessons with a bass teacher and more performances.

Outside school, moreover, his interests and talents have been helped by the work of brilliant West Country-based charity Evolve Music, who put on SoundLab, a weekly youth club for learning disabled and neurodivergent young people where James plays, learns – and, in his own way, socialises.

There are two massive issues that all this flags up. One is to do with the decline of music in state schools, and the overlooked fact that this has hugely affected autistic and learning disabled children and young people.

As schools have been gripped by cuts and told to concentrate on English, maths, languages and science, music education has entered an ongoing state of crisis.

The absence of a music teacher would have made inclusion much harder and more complex

The statistics are eye-watering: between 2010 and 2023, the number of people training to be music teachers more than halved. In our case, the absence of a music teacher – Miss Parsons, and we’re still in touch – would have made inclusion for James immeasurably harder and more complicated.

The other issue is even bigger. Towards the end of Maybe I’m Amazed, there’s a chapter full of questions about autism, learning disabilities and adulthood.

Through James’s life so far, what has often kept us going is a sense of momentum: the feeling that with enough effort and belief, possibilities will unfold, and allow him to somehow reach his potential.

But part of the attitudes and prejudices that too many institutions enshrine is a strange belief that education has to end at some arbitrary deadline, and that autism in particular is something exclusively to do with childhood. The result, if you’re not careful, is a sudden sense of possibilities shrinking.

A lot of people reading this will know what this feels like: dispiriting occasions when you sit in some spartan meeting room, and have leaflets pressed on you about unpaid shifts in charity shops or garden centres.

I think I know what would suit James, but it sounds almost utopian: a kind of neurodivergent music school, with an abundance of technology and the chance to develop his talents for as long as he liked.

Only last week, I watched him spend a day creating meticulous PowerPoint presentations about the discographies of The Strokes, The Beastie Boys and Mott The Hoople, before he spent an hour teaching himself how to play The Beatles’ The Fool On The Hill on the acoustic guitar; next Friday, he will resume his sessions at SoundLab. But what can he do to further develop all that?

James is now 18: our fear is that, beyond our home, there will be no provision that taps into all these appetites and talents – a door will be slammed when he reaches his early 20s, and we will find ourselves in a make-do-and-mend reality of day centres and occasional trips out.

Surely, after all these years of increasing knowledge of autism and the complexities of human psychology, there ought to be a lot more than that, accessible to everyone who needs it.

In our case, what psychologists and educationalists now know about the profound links between neurodivergence and music ought to begin to open up a whole new area of provision, but I fear we will be waiting for an impossibly long time.

Ambition not impairment

There is a vast amount of joy in the life we share with James, and how it changes and evolves.

It comes to us not just through music but also his other talents and interests, and how much they have blossomed: art, cycling and his amazing fondness for hillwalking, which has taken us on ambitious hiking trips around the country, and earned James two Duke of Edinburgh awards.

What all this vividly shows is there every time he picks up a guitar or makes his way up a mountain: the fact that our kids can’t be endlessly pathologised and problematised or reduced to deficits and impairments.

This is the lesson at the heart of Maybe I’m Amazed, and it needs to be absorbed into not just our systems of education and care, but the whole of society.

Maybe I’m Amazed: a Story of Love and Connection in 10 Songs, published by John Murray, is out now

John Harris is a Guardian columnist who writes on subjects including politics, popular culture and music