Simon Jarrett reviews Joseph Conrad’s 1907 book Secret Agent featuring simple-minded Stevie. It was published one year before the report of the Royal Commission on the Care and Control of the Feeble-minded. This lead to the Mental Deficiency Act and an era of lifelong detention in mental deficiency colonies or strict community surveillance for those branded ‘deficient’.

The Secret Agent: A Simple Tale

Joseph Conrad, 1907

(Penguin Books, 2007)

Sabotage, Film, 1936

Dir. Alfred Hitchcock

The Secret Agent, BBC Drama, 1992

Dir. David Drury

The Secret Agent, Film, 1996

Dir. Christopher Hampton

[restrict]

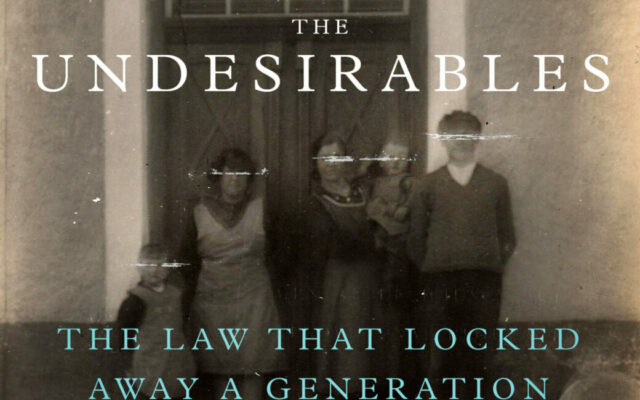

The year 1907 was not a good one to be a person with learning disabilities. The pseudo-science of eugenics, the idea that ‘feeble-mindedness’ was caused by hereditary degeneration in the lower orders of society, had become a mainstream belief across broad sections of public opinion. ‘Idiocy’ and criminality were linked together in the public mind, both believed to arise from degeneration. The feeble-minded person was seen as a dangerous presence, threatening to overwhelm the healthy stock of the nation.

Conrad’s Secret Agent was published one year before the report of the Royal Commission on the Care and Control of the Feeble-minded. This would soon lead to the Mental Deficiency Act and an era of lifelong detention in mental deficiency colonies or strict community surveillance for those branded ‘deficient’.

At the heart of Conrad’s ‘simple tale’ is Stevie, a simple-minded young man who spends most of his time drawing circles on pieces of paper. He is looked after by his sister Winnie. She is married to Verloc, owner of a pornography shop and a secret agent working on behalf of the Russians.

Verloc is instructed to carry out a bomb outrage at the Greenwich Observatory to discredit London’s refugee revolutionaries, seen as a threat by the Russian government. He realises his brother-in-law Stevie is the ideal person to plant the bomb – he is ‘willing, docile, ready to please and even useful’. Stevie makes his way into Greenwich Park, loyally carrying the bomb, with disastrous consequences.

In Conrad’s portrayal we have an insight into the early 20th century idea of those deemed the least intelligent and therefore outside the accepted margins of human society. Stevie had ‘a vacant droop of his lower lip’ as he ‘prowled around the table like a frightened animal in a cage’. He is ‘a terrible encumbrance, that poor Stevie’, coldly described by one of the anarchists as ‘typical of this form of degeneracy’. His life is expendable.

Conrad’s work has subsequently fascinated and influenced film-makers. Alfred Hitchcock’s 1936 film Sabotage is based on it, but in his version the Stevie character becomes a naïve and gullible schoolboy. The BBC made a three-part series in 1992 and Christopher Hampton a film in 1996, both of which remained true to Conrad’s original vision of Stevie as ‘half an idiot.’

Two BBC programmes gave a strong voice to the victims of post-war experiments

Disowned and Disabled BBC 4

1. Nowhere else to go – 29 October 2013 9.00pm

2. Breaking Free – 30 October 2013 9.00pm

Credit to BBC 4 for two intelligent, lucid documentaries charting the post-war experience of British children who found themselves outside the mainstream, either through physical or learning disability or some other social and family circumstances that made them ‘misfits’.

Among their many creditable features was the strong voice given to those who had experienced the system.

The first programme tackled the ‘disowned’ part, the sad history of those falling into the care of the state, (and the voluntary sector) because they were orphaned, neglected, illegitimate or troublesome. There was a distressing litany of abusive treatment wherever the system sought its remedies. The 1948 Children’s Act, promising a new era of individualised care, partly arose from the beating to death of a boarded-out child by their ‘carer’ in 1944.

But the scandals and abuse never went away, simply reappearing in new forms, from mass transportation to Australia and Canada to new experimental regimes such as the brutal ‘pin down’ system and use of drugs.

Horrendous

As thinking moved from institutions to the birth family as the child’s best bet, there was a string of horrendous child-deaths at the hands of their families, and once again the state stood accused of letting down its most vulnerable. It was striking how often even the most abusive experiments were based on ‘solid research’.

The second programme charted the post-war experience of disabled children and, pleasingly, achieved a judicious balance between physical and learning disability, not usually a strong point of disability programming. The era began optimistically with the 1944 Education Act promising mainstream education, but no resources accompanied the promise and the powerful special interests of medicine, education and psychology resisted integration. Asylums persisted and, outside them, large numbers of ‘ineducable’ children remained at home.

It was marvellous, and moving, to see the great self- advocate, Mabel Cooper, telling one last time the story of her life from childhood to middle age in St Lawrences Hospital. She was interviewed shortly before her recent death, clearly very ill and unable to sit up. Yet her spirit, and the power with which she could convey her story and its messages, were undimmed.

Mabel was scathing about the mental straitjacket into which the system placed her. “You didn’t learn those things that you need to learn out in the world. They taught us colouring and all that. I’d rather learn something than do that”.

Brian Rix, the famous actor and former head of Mencap, spoke of the birth of his daughter Shelly, who had Down’s syndrome, in 1951. He was asked by doctors, trying to work out why he had had a disabled child, if he was a drinker, or had venereal disease. The advice was to ‘put her away, forget her, start again.’ He visited St Lawrences, where Mabel Cooper lived. “I saw three or four thousand people, shambling around the grounds with nothing to do. It was appalling”.

Closure

The journey towards the Community Care Act and the closure of the institutions was charted, including the public outrage caused by the 1981 Silent Minority documentary which showed, again in St Lawrences, the teenage patient Nicky, tied to a post in the ward for five hours a day to stop him wandering.

The programme ended optimistically; the ground-breaking civil rights basis of the 1995 Disability Discrimination Act, the reduction in special schooling, the impact of the Paralympics and the emergence of the social model of disability.

Simon Jarret

[/restrict]