Small victories, big difference

Small victories, big difference

It’s not about being angry – it’s how you use this, says Simon Cramp, reflecting on his work to improve the lives of people with learning disabilities. Seán Kelly meets him

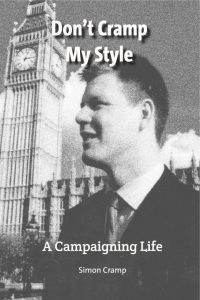

‘I hope it’s a book that is not just about how good I am – I hope it is also about changing government policy by making small victories with a lot of help from other people,’ says Simon Cramp, a self-advocate and campaigner with learning disabilities.

While the title of Cramp’s book, Don’t Cramp My Style, is an amusing pun, given his life and his passion to create positive change, it is difficult to imagine anyone managing to cramp his style in any way.

The book tells Cramp’s life story, setting it against the backdrop of policy developments and scandals in the UK that affect people with learning disabilities. Cramp wrote it because he had been disappointed on reading Alastair Campbell’s diaries covering his time in the Blair’s Labour government. ‘It was all about him,’ he says, and did not cover wider developments sufficiently.

The story starts with his birth in 1971 as one of a pair of twin boys. Neither brother started breathing soon enough after the birth which led to them both having learning disabilities and various health problems. Simon’s brother

Adrian’s learning disabilities were ‘a bit more severe’.

Because of this, Cramp has dedicated much of his life to improving matters for people with profound learning disabilities. Adrian sadly passed away about three years ago but his older brother (by eight minutes) has continued as a committed campaigner.

As he grew older, Cramp became involved with the local Mencap group. He first came to the attention of National Mencap at the organisation’s conference in 1998 aged 27 when he made an impassioned speech in favour of people with learning disabilities having voting rights within the organisation.

He cannot remember his exact words: “Forgive me Sean – it’s nearly 20 odd years ago – but it was something like: ‘If you don’t give us the chance that we can do this, how will we ever know whether we can?’ ”

He spoke from the heart with passion and clarity and the effect on the conference was electrifying. When the vote was taken, the huge majority needed for the rule change was achieved. There was uproar, Cramp says.

A photo of him, eyes closed and punching the air, surrounded by supporters, went across the world.

‘I did a You and Yours radio interview, I did the Guardian, I did most of the national newspapers and my picture appeared even in Australia and places everywhere around the world. It went global. You know – “charity gives a voice for people with a learning disability”.’

Not surprisingly, he soon found himself voted onto the national assembly and then the board of trustees. For a self-advocate, he describes this as being like a footballer who suddenly finds himself in the premier league.

‘It’s quite a big leap. Once you get into those positions it’s not about ‘What are your problems?’ You are there to do a job for other people because they have elected you and it’s a completely different ball game,’ he says.

The position at Mencap led on to Cramp becoming a member of the Royal Society of Medicine Intellectual Disability Forum. He says his biggest honour there was being asked to chair a symposium for the society at the House of Lords.

Other red letter days that feature in the book include going in top hat and tails with Lord Rix of Mencap to St Paul’s Cathedral to celebrate the Queen Mother’s 100th birthday, and being called to 10 Downing Street to meet Prime Minister Tony Blair.The book includes numerous positive tributes and testimonials from people he has worked with.

‘Perhaps I am blowing my own trumpet for some of it,’ he says. However, he adds: ‘You can’t do campaigning all on your own. If you are a lone voice, then people at the Department of Health & Social Care and other government departments don’t listen to you.’

He is keen on sophisticated campaigning methods: ‘The days of chaining yourself to a government building are long gone. You have to be a bit smarter.’

He is delighted to have been described as a ‘world class networker’ by Alicia Wood, the former chief executive of Learning Disability England (when it was Housing and Support Alliance), and others.

One absence in the book is the voice of other self-advocates. Cramp explains: ‘Unfortunately, I didn’t quite get to speak to any self-advocates because they were in different parts of the country and I have lost touch with some of them. That was one of my downsides.’

He points out, however, that they are mentioned in a contribution to the book written by Don Derrett, a pioneer of self-directed support, who worked with him at Mencap.

Elsewhere in the book, David Wolverson, the former chief executive of Dimensions, writes: ‘When you take even one step in Simon’s shoes, I wondered how he had not become an angry young man.’ To this, Cramp responds: ‘I became an angry man! But it’s about how you use it.’

He tells of being at a meeting years ago at the Home Office. ‘I was getting quite angry and quite bolshy, and at times bordering on being rude because I was still learning my trade,’ he recalls. He quickly caught on that he would not be invited again and so he learned to be more professional in his criticisms.

Making the law

Cramp is particularly proud of having been involved in the development of the Mental Capacity Act 2005. With others, he successfully campaigned for the inclusion of advocacy including the requirement for independent mental capacity advocates. Mental capacity continues to be a concern for him.

‘That’s one of my babies. That is one of the things that I am so passionate about. I will fight you to the end in debates and try to make you see my point of view [over mental capacity]. I don’t care who you are – whether you are a doctor or whatever,’ he says.

He finds it amusing that the act was nearly invoked in his own case. He was in hospital for a CT scan and the doctor was going through the checklist before the procedure. He was having one of those days where his dyspraxia made it hard to process information and he had trouble understanding one of the words.

When the physician began to question his mental capacity, Cramp derived some satisfaction from saying: ‘I beg your pardon. I was one of the people that made sure that act actually happened.’

A hero and inspiration is ‘bless him, Brian Rix’. The late Lord Rix – an actor in saucy stage farces that were popular in the 1950s and 1960s – is well known as a founder and chair of Mencap.

Rix was a classic ‘luvvie’. Whenever Cramp met him, Lord Rix used to say ‘Hello, love, are you alright?’ and, if Cramp needed help with something, he would always say: ‘Yeah, love, leave it with me.’

Rix’s willingness to drop what he was doing to help Cramp probably caused ‘a few narked faces on Mencap senior management’.

‘I just loved him to pieces – as a bit of a father,’ he says.

In turn, Cramp helped Rix manage a difficult situation in the House of Lords, by suggesting that some tricky and confusing amendments to a bill were withdrawn and rewritten. Rix took his advice and Cramp is proud that he was able to help him in return.

He is also proud that Rix’s son Jonty has written one of the forewords to the book. Another of the forewords is written by Guardian correspondent David Brindle.

Cramp is amused by Brindle’s approach: ‘I think David puts it nicely when he says this is quite a disorganised book but, if you want a scholar’s thing, an academic book, then don’t buy this book. I think it’s perfect, you know.’

In truth, it is an unusual and very personal book – and it strongly reflects the character of its author and central figure.

Towards the end of the book, he half- jokingly suggests that, maybe, one day he will become ‘Lord Cramp of Chesterfield’. This comment says a lot about him, displaying his sense of humour and his undeniable ego, as well as his dedication to public service. It is almost impossible not to chuckle at his cheek but, on the other hand, a seat in the House of Lords might suit him very well indeed.

Don’t Cramp My Style: a Campaigning Life can be downloaded as a pdf or purchased as a hard copy from the Centre for Welfare Reform website: www.centre forwelfarereform.org/library/by-az/dont-cramp-my-style.html

Don’t Cramp My Style: a Campaigning Life can be downloaded as a pdf or purchased as a hard copy from the Centre for Welfare Reform website: www.centre forwelfarereform.org/library/by-az/dont-cramp-my-style.html

Sean Kelly was chief executive of the Elfrida Society from 2001 to 2012 and is now a freelance writer and photographer