Is anybody noticing?” These words from my sister Raana are quoted at the start of my anthology, Made Possible, and they permeate through the entire book. Raana, who has fragile X syndrome, is the reason for my non-fiction collection of stories of success by people with learning disabilities.

The idea for a book came from seeing my sister grow up and become more independent. I wanted to write about Raana’s potential and personality to challenge society’s negative attitudes towards learning-disabled people. More widely, the book is driven by my frustration that society fails to recognise the potential of people with learning disabilities. And this makes our communities all the poorer.

Success, as I write in the introductory chapter, is a crucial part of being human. But what if society doesn’t think success and aspiration apply to you? We do not hear people with learning disabilities talk about talents; when Raana was a child, she would not have been asked, “What do you want to be when you grow up?” The book also challenges stereotypes about learning disability, arguing that we should embrace and encourage the contributions of learning disabled people, instead of pitying or patronising them or seeing them in simple terms of either triumph or tragedy.

As fine artist Laura Broughton explains in her essay, “society treats you a little bit like a child” if you have a learning disability.

Made Possible reflects the rise in campaigning, grassroots activism and self-advocacy across the learning disability movement. A critical aspect is that the stories are written in the first person, so each contributor takes control of the narrative and we hear from them directly – a rare occurrence in the mainstream media. “Success,” as Made Possible contributor and human rights campaigner Shaun Webster says, “is about believing in yourself and making your own decisions”. The fact that the stories are told in the first person also reflects the sense of unease I felt when writing articles about learning disability issues. I felt my reporting did not give people’s stories enough room to breathe and, as much as a neat, punchy case study can humanise a piece of journalism, it can never convey the full measure of a person.

Another reason for the book is that I wanted to explore how today’s negative perceptions about learning disability are a hangover from the past – from the days when people used to be even more segregated and hidden away.

The long-stay hospitals may have been closed decades ago, but their institutional approach lingers on in many care settings today. People in supported living are routinely encouraged to go to bed at 8.30pm, for example, and more than 2,000 people with learning disabilities and/or autism are still stuck in assessment and treatment units, which are modernday institutions (James et al, 2017; NHS Digital, 2020).

Learning disabled people experience worse healthcare than the rest of the population. This shocking fact was clear in the latest annual Learning Disabilities Mortality Review, which provided yet more evidence of preventable early deaths (University of Bristol, 2019). In employment too, there is a stark equality gap, with fewer than si x per cent of learning-disabled people in work (Hatton, 2017). The backdrop to this is years of austerity that have further undermined life chances and involved public sector spending cuts to special needs education or social care.

x per cent of learning-disabled people in work (Hatton, 2017). The backdrop to this is years of austerity that have further undermined life chances and involved public sector spending cuts to special needs education or social care.

Now with Covid-19, these inequalities are intensifying. Death rates of learning disabled people have doubled during the pandemic in the UK and the social isolation many already experience has worsened under lockdown. Daily routines and activities have vanished and there have been serious issues with supply of equipment such as gloves and masks as well as with coronavirus tests.

This makes it all the more important that we hear stories about what is possible directly from those with lived experience. The contributors to this book are a diverse range of trailblazers who have excelled in competitive fields such as film, theatre, music, art, campaigning, politics and sport. The eight remarkable people who share their life stories include veteran civil rights campaigner Gary Bourlet. In an inspiring essay, the co-founder of Learning Disability England reflects how far we have come with equality – and how far is left to go.

There is a beautiful chapter about the art of acting and a powerful argument for wider representation of learning disability on stage and screen from Sarah Gordy, who was recently seen in BBC drama The A Word. Filmmaker Matthew Hellett, lead programmer of Oska Bright, the biennial learning disability film festival, makes an equally passionate plea for this in his essay. Also reflecting success in the arts sector is artist Laura Broughton, the first learningdisabled woman to have a work accepted for the Royal Academy’s summer exhibition. She movingly describes the challenges of being in “Laura’s world”, where people fail to make the reasonable adjustments that would make communication easier. Another arts professional, singersongwriter Lizzie Emeh, explains how her potential was unlocked by the right support and outlines her ambitions to help more learning disabled people achieve their dreams.

Other contributors include Gavin Harding, the UK’s first mayor with a learning disability. He recalls his rise in local politics and harrowing years spent in institutions. Paralympic swimmer Dan Pepper describes his competitive career as well as the strong network of family and friends that enabled him to succeed. Each story is unique; each storyteller’s voice is different. But what unites the chapters is their determination, singleminded vision and belief that everyone has value and can contribute to society – with the right support.

For those with experience of learning disability, I would like Made Possible to leave them feeling inspired, motivated and positive about the future. For readers with no knowledge of the issues, it should encourage them to think twice about a group of people too often regarded as second-class citizens.

Another aspect of the book is vital. Made Possible highlights the grand achievements of groundbreaking people, achievements that would be remarkable regardless of any disability. It also argues that everyone should be able to define their own success, and that this co mes in many forms. My sister might not have won any medals, performed on national TV or made speeches to a packed auditorium but her “everyday success” is just as significant. It is worth not only acknowledging but also celebrating. Raana has moved to a more independent life in supported living and, before lockdown, was doing her own shopping and using local buses.

mes in many forms. My sister might not have won any medals, performed on national TV or made speeches to a packed auditorium but her “everyday success” is just as significant. It is worth not only acknowledging but also celebrating. Raana has moved to a more independent life in supported living and, before lockdown, was doing her own shopping and using local buses.

Raana’s story of success will be familiar to many families and carers. My family fought for the right support, navigating the revolving door of professionals including, to name a few, health visitors, GPs, paediatricians, special educational needs coordinators, social workers, care managers and speech and language therapists. Raana’s success is also down to the dedicated, enlightened individuals who have supported her over the years. She thrived at her mainstream secondary mainstream school, Angmering in Sussex, leaving with one GCSE (a grade C in art and design), a commendation award and a letter of achievement from the head teacher “for setting such a positive example to other students”.

Of course, Raana’s achievements are also down to her own determination, resilience and engaging personality. With the right support, she feels more confident and she thrives. I hope that Made Possible will encourage us all to be more honest about what support we all need to reach our goals, and how this unites us.

In an early editorial discussion about what help he had to fulfil his ambitions, champion swimmer Dan Pepper rightly turned the tables on me and asked: “Who’s helped you to be here today?” We all need support of some kind.

This ultimately uplifting book shows that everyone has value, everyone can contribute to society and, as my sister says, we just need to notice that. Society should be as aware of the rights of learning-disabled people as it is of debates on gender,  race and sexuality.

race and sexuality.

Sir Norman Lamb, chair of South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and former health minister, has said the book must act as “a call to arms to confront continued discrimination. It shows what’s possible. Made Possible must become the reality for all those with a learning disability.”

For contributors such as Harding, it is equally important that their stories inspire others to keep challenge the status quo: “I’ve broken barriers, and I’m proud of what I’ve done, but the most important thing is that what I’ve done inspires other people. I was the first councillor with learning disabilities and then the first mayor. I was the first, and I shouldn’t be the last.”

● Review, page 29

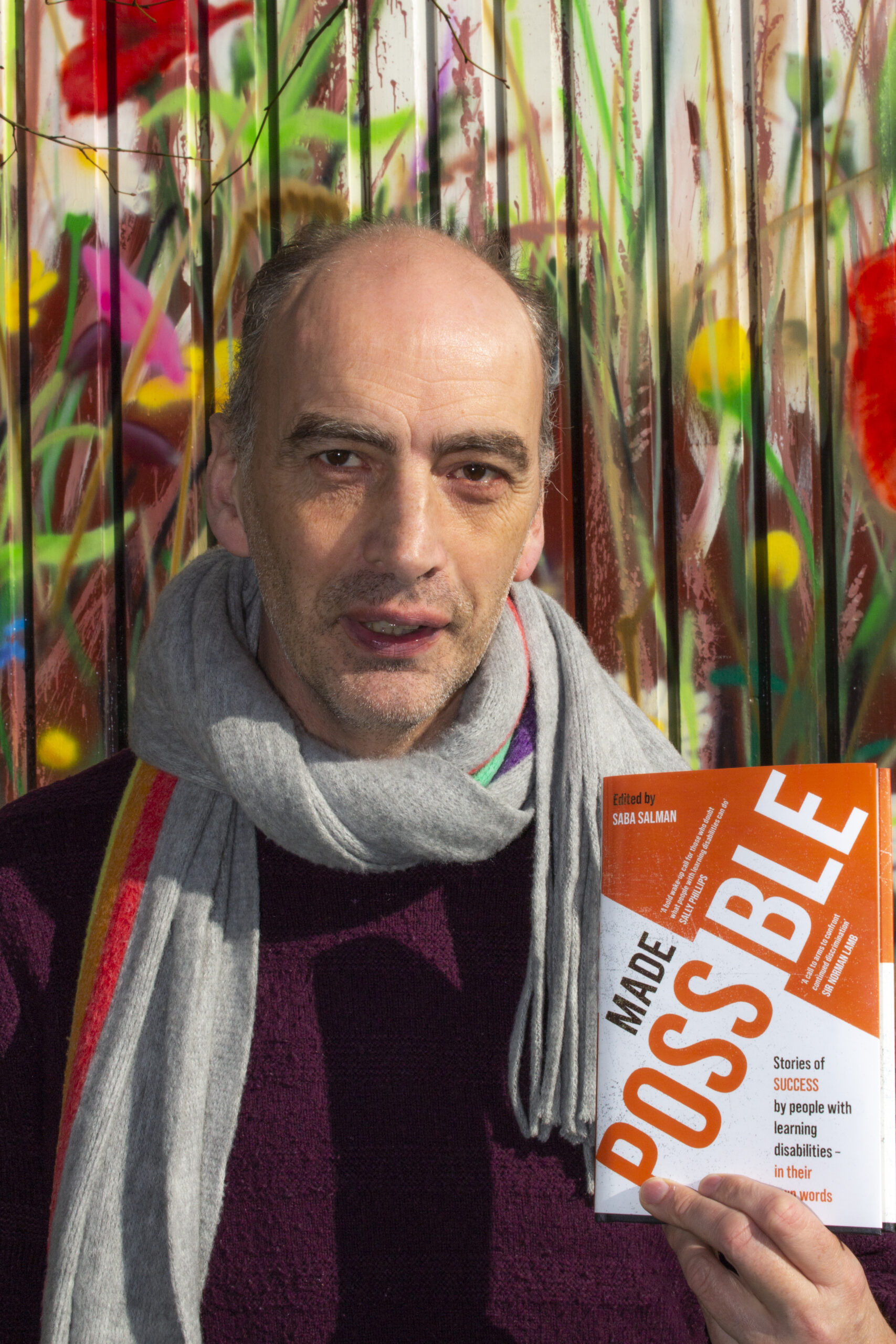

Saba Salman is a journalist and author, and the editor of Made Possible: Stories of Success by People with Learning Disabilities – in their Own Words. Unbound, 2020, £9.99 paperback; £4.31 Kindle

References

Hatton C (2017) Employment Statistics: Quick Update (November 2017). Blog. https://tinyurl. com/yyu3a7p4

James E, Harvey M, Mitchell R (2017) An Inquiry by Social Workers into Evening Routines in Community Living Settings for Adults with Learning Disabilities. University of Lancaster. https://tinyurl.com/yy9engsl

NHS Digital (2020) Learning Disability Services Monthly Statistics (AT: June 2020, MHSDS: April 2020 Final). https://tinyurl.com/y2cqcwq2

University of Bristol (2019) Learning Disabilities Mortality Review(LeDeR) Programme. Annual Report 2019. https://tinyurl.com/y6sotjgm

Photo Credits

Felipe Pagani: Lizzie Emeh on stage;

Rob Gould: Sarah Gordy, Rob Gould: Saba and Raana Salman;

Carousel: Matthew Hellett