Back in March, we were in the middle of an Arts Council-funded poetry project for Mencap, capitalising on its status as the official charity of the 2020 Virgin Money London Marathon.

We were looking forward to interviewing members of Team Mencap about how runners with learning disabilities pushed through the 19th mile – notoriously the point in a marathon where people feel most tempted to give up. And we had planned to broaden out to learn about other moments in their lives when they had almost admitted defeat, and how they’d picked themselves up, dusted themselves down and taken that crucial next step.

We could never have predicted that we were about to face our own 19th miles. When lockdown hit, Emma had to face down the difficulties of separation from her sister, Louise, who has profound and multiple learning disabilities and lives with their elderly parents. They devised a care plan in case their parents caught the virus and became too poorly to support Louise. Emma sourced PPE and kept a packed suitcase in the boot of her car, ready to make the long journey to her family home.

In the meantime, it was crucial that they didn’t all fall ill at the same time. So Emma had to accept that the best way she could help was to stay away. Clare’s parents, on the other hand, live close by. When she was advised to shield because of her severe asthma, she faced her own 19th mile. As a woman with learning disabilities in her mid-40s, should she self-isolate alone in her flat or give up her hard-won independence? It felt like an impossible choice.

During the long months of Clare’s shielding, we kept in touch and collaborated over video call on poems documenting Clare’s experiences of the pandemic. We would explore possible topics and Clare would often go off to write a first draft alone. On the next call, we’d bat around ideas for developing the draft, digging for detail by exploring sensory appeals, and discussing the best form for expressing Clare’s ideas.

We are pleased to share a selection of these poems, which feature in Growing Wild, a collection charting a varied experience from Clare’s claustrophobia during weeks alone to her joy at returning to an allotment abundant with fruit. In these poems, we dared ourselves to venture to the darkest chasms of isolation while always taking in our sight brilliant vistas of hope.

Clare Manley works for the NHS as an access health champion, advocating for the needs of patients with learning disabilities. She is also a trainee at a social enterprise that prepares adults with learning disabilities to work in horticulture and hospitality. She is a founder member of their poetry club, and one of her poems is published in The Memoir Garden: Poems from the Words of Adults with Learning Disabilities (Two Roads, 2013). Since the beginning of lockdown, Manley has been documenting her experiences as an adult with learning disabilities by writing poems about the pandemic.

Emma Claire Sweeney is the author of Owl Song at Dawn (Legend, 2016), a novel inspired by her sister who has cerebral palsy and autism, which won the Nudge Literary Book of the Year award. Sweeney’s debut non-fiction book, A Secret Sisterhood: the Hidden Friendships of Austen, Brontë, Eliot and Woolf (2017) was written with her friend Emily Midorikawa and has a foreword by Margaret Atwood, who described the work as a “great service to literary history”. She has won Royal Literary Fund and Society of Authors’ awards, and her work has appeared in Time magazine, The Washington Post and The Paris Review.

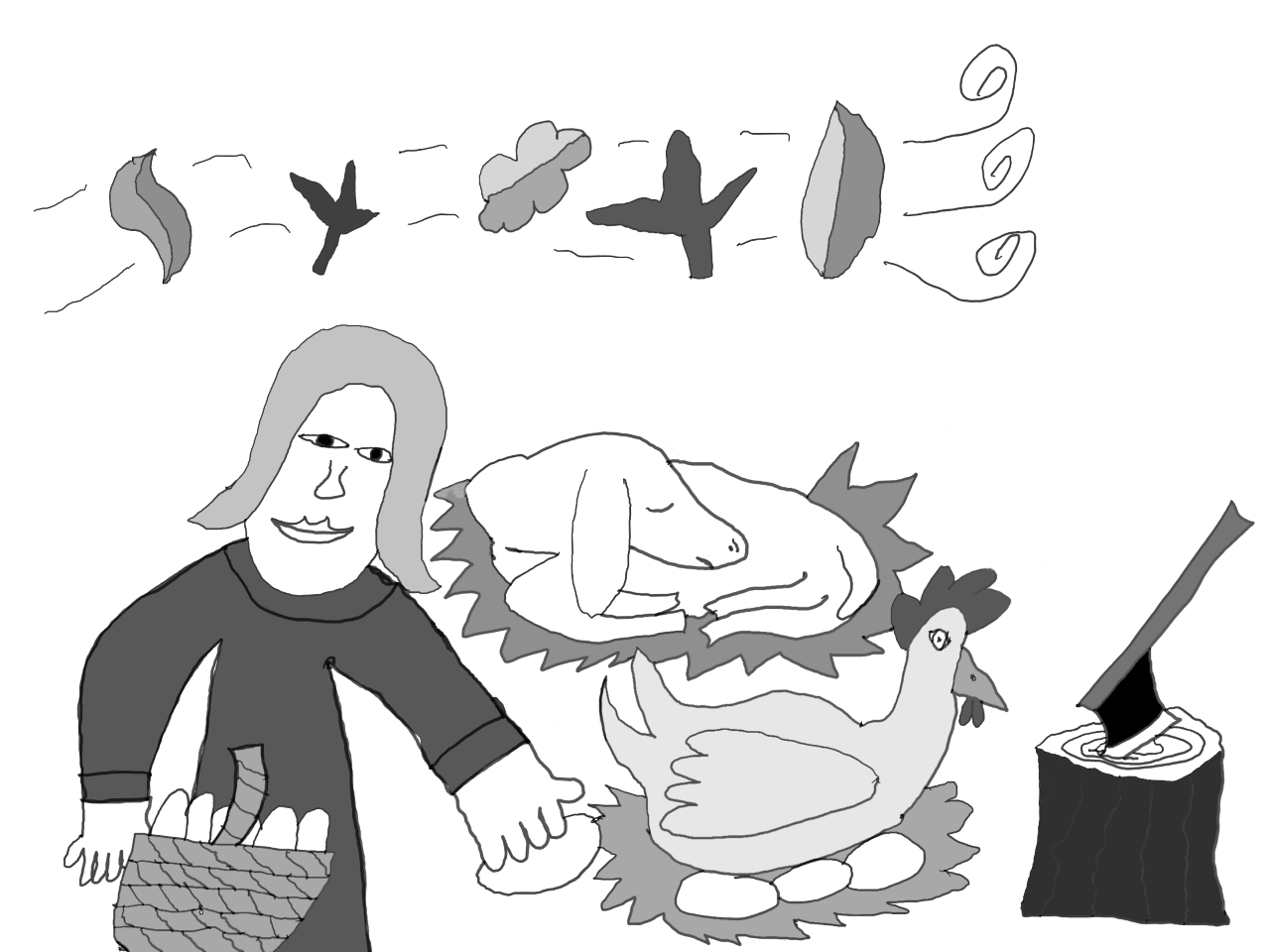

Grow Your Own

I filled a huge suitcase

with joggers and jumpers and loose cotton dresses,

a mixed-berry bath bomb,

and wireless earphones.

I left behind

Roland Rat and my teddies.

No need, my mum said,

for children’s toys.

From Mum and Dad’s tub,

I looked out over their neighbour’s overgrown garden.

No bath in my flat.

For years, I’d fought for a walk-in shower.

Dad needed space alone to feed the dog.

Mum fed us fish and chips and Sunday roasts.

I should help with the cooking, she said.

But I thought of myself as their guest.

And yet, I couldn’t stay still,

cleaning the loos,

dusting and polishing the lounge.

No good for my lungs.

I weeded their borders,

sowed broad beans, sweetcorn, sunflowers.

They took months to grow,

and flowered for only two or three weeks.

From April to August,

my neighbour watered my garden,

tending the daffodils and fuchsia I’d planted before.

I descend hillsides and emerge from woodlands before the August sky burns blue, the air becomes woollen damp.

My sister’s chickens cluck on their warm clutches, as I fetch their blue eggs from behind.

When the day moults to dusk, the sheep bleat for their evening feed before curling quietly in the hay. Hints of autumn spike the air – the slaughterhouse still a month away.

The Lockdown

Bins of tissues,

every cough, sneeze and tear.

Empty packets,

chocolate buttons, lemon drizzle, custard creams.

Oh, for lungfuls of air,

allotment fresh.

Oh, to sow

Swiss chard and hug my friends.

But the gatekeeper

butterflies

have flit from the brambles

to my belly.

I only let certain people get close,

But how will I endure isolation all summer long?

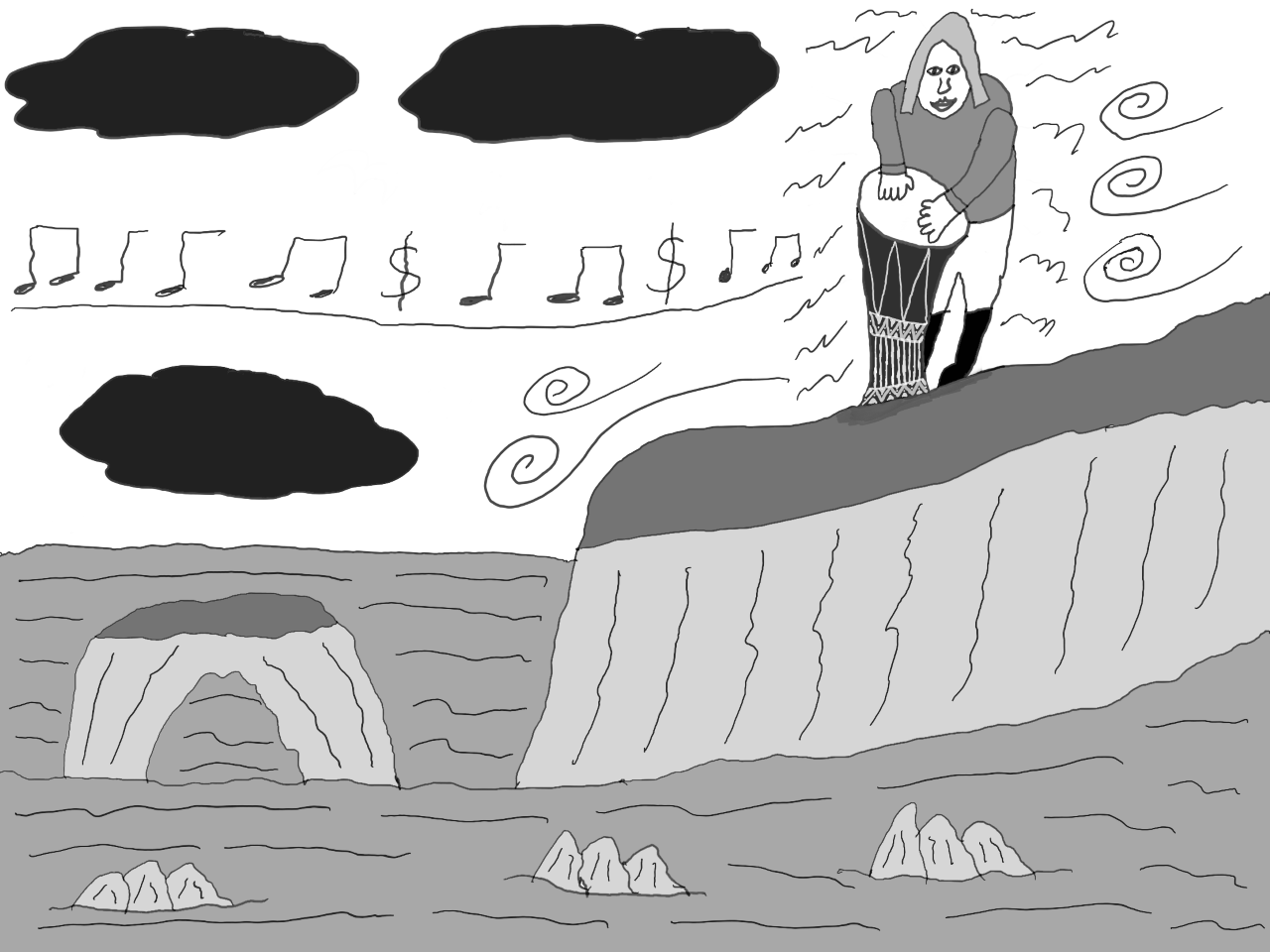

Picnics in the Rain

When the sun is out, our conversations shine brighter.

Autumn creeping close, we climb Cornish cliffs,

our limbs hard-worked, lungs sea-air tired, our last gasps before the seasons shift.

Virtual discos, my song grows wild, yet the canal’s edge grips tightly.

For beneath black clouds my breath labours quietly.

In chill

air, though,

my drum speaks,

my muffled taps edging

towards a far heavier beat.

At picnic tables, they open umbrellas, the people who gather to the beat of my drum,

pensioners, toddlers, addicts and couples long wed,

beneath the hush of the willow, they hear my life thrum.

One Hundred and Two Days Away

The grass colour-sapped and head-height,

hiding trailing hawthorn and broken glass.

I’m stiff-limbed from strimming and raking,

Picking red currants with friends,

our laughter reaching across the spade lengths between us.

Pete, a walking scarecrow,

moustache and beard dyed green for the NHS.

The eye sting of onion and runner-bean chutney,

the bitter-sweet smell of loganberry jam.

Sterilised jars to stock the pantry before the return of wintry days.

The Right Time

Time to move,

I told them.

It was time, Dad agreed.

Months to find a social worker; years to find a flat.

Full of lads, it was,

and a waterlogged cellar.

Rising spores that clogged my lungs.

Finally, I moved to a house by the canal.

Seven years, I’ve lived here.

Own front door, own back door,

own rocking chair and cushions,

own unicorn handwarmer and unicorn toys.

In March, I turned over the soil, planted daffodils and fuchsia.

I was looking out the window when my boss called. We’re closing the office,

she told me. How long, I don’t know.

Weeks I spent, alone: No support staff, no friends.

Still, I rose early,

fried bacon and eggs on Mondays though I couldn’t work at the allotment.

Still I spooned porridge with golden syrup, though I couldn’t take the 500 bus to work.

Alone,

I could hear the whistle of tits and robins,

my neighbour practising his saxophone,

the scrape of their chairs at mealtimes,

the hum of their talk.

I texted my parents.

I think it’s time, Mum told me.

Time to return.