“I took everybody into the dining room and put a table against the door so the staff couldn’t get in.”

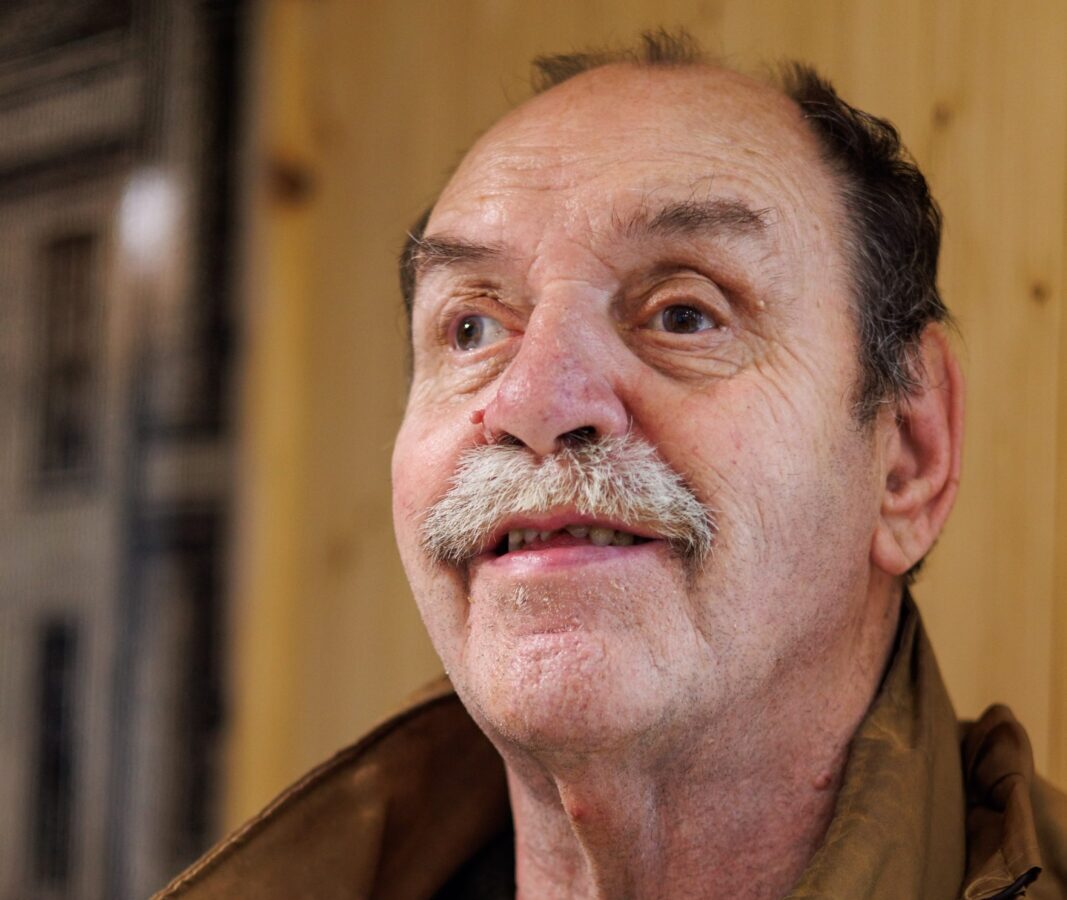

Michael Edwards is describing a protest at the day centre he used to attend as a young man.

Edwards, veteran campaigner and founder and president of charity My Life My Choice (MLMC), had spent the morning sorting out small industrial components. He became angry at lunchtime when he and other attendees found staff mixing them all up again so everyone had something to do in the afternoon.

He is silent for a moment as he remembers. “We said: ‘We are going to stay here until you sort them out.’ ”

Did the staff eventually knuckle down and sort out the components themselves? “Yes they did,” he laughs, before adding: “They didn’t do that a second time.”

Edwards is partially sighted and has learning disabilities. The 72-year-old has largely negative memories of the day centre era and attitudes of staff at the time: “We were told what to do and when to do it by.

People in institutions were not encouraged to speak up. If you did, they didn’t like it

“The trouble was people were living in institutions and they weren’t encouraged to speak up. Or, if you did speak up at the centre, they didn’t like it. Well, I thought, this is not right.”

Putting it right

However, he and his peers had an ally in a social services employee called Chris Lock.

“I got on with him. He took me to London a couple of times for various meetings. His attitude was: ‘Come on, we have got to do this.’ ”

Edwards attended conferences and heard about burgeoning self-advocacy groups in the 1980s and 1990s.

Frustrations led Edwards and three other day centre attendees to start a self-advocacy group: “I went up to People First in Nottingham and that’s when the idea came. Well, why can’t we do it?”

In 1998, they established self-advocacy charity MLMC.

Oxford-based MLMC now employs 10 full-time office staff and five paid consultants who have learning disabilities. It has about 860 members and 15 trustees, all of whom have learning disabilities and are supported to make decisions by paid helpers.

Crucially, Edwards says, the helpers are there to make sure trustees understand the decisions they have to take, not to suggest what they think are the best options, because, as Edwards says: “That would defeat the object.”

The charity offers a wide range of services and activities around Oxfordshire.

For example, more than 200 people attend its monthly self-advocacy groups and a similar number use the Gig Buddy project, where members are matched with a volunteer buddy with shared interests so they can go out together.

Just over 80 people are working with the Travel Buddy project, which offers support to build skills to travel independently.

MLMC also runs campaigns (see “Why experts by experience pulled out of care and treatment reviews,” autumn 2022) and is involved in research. This can involve co-researching or joining steering groups with academics from, for example, Manchester Metropolitan University, the Open University and the University of Oxford.

Other work includes its Computer Buddy scheme, which aims to get people access to devices and learn new skills, and a monthly night club, Stingray, exclusively for people with learning disabilities.

Members are paid if they work for the organisation. MLMC has a jobs and money team that deals with personnel issues. “You have got to do it properly,” says Edwards, “or you end up in court.”

Funding has been tough. He recalls: “There was a point where we nearly closed because the funding got low but we managed to get round it. We tightened our belts. We had to get rid of somebody – not because we wanted to.”

MLMC is part funded by the National Lottery and charges for some of its consultancy services, such as reviewing services or creating easy-read documents.

Edwards is aware advocacy groups have been closing across the country because of financial difficulties. He recommends building local support by getting onto local or national radio. At one time, he adds, MLMC used to produce a local radio programme

He still has hopes of appearing on BBC radio shows such as In Touch and You and Yours.

Campaigning

MLMC was also deeply involved in the Justice for LB Campaign.

Connor Sparrowhawk, known as Laughing Boy (LB), had an epileptic seizure and died in the bath in 2013 while in an inpatient unit in Oxford run by Southern Health NHS Foundation Trust. His death was found to have been preventable and the trust admitted systemic failures.

People in social services are now a lot different. I think they are taught a bit of advocacy and how to help people rather than tell them what to do

Edwards recalls protesting in the street with other campaigners. He was also at the hearing and heard the NHS trust’s defence.

“What I didn’t like was sitting there all day listening to the waffling – oh, I didn’t like that.” Connor’s mother Sara Ryan has been patron of MLMC since 2018.

Does Edwards think things have improved for people with learning disabilities in the almost three decades since he started MLMC?

He is sure they have: “The people in social services are a lot different to what they were when I was young. I think they are taught a bit of advocacy and taught how to help people rather than tell them what to do.

“Where possible, they consult users. It is not always possible because some people just cannot communicate and they have to have their best interests at heart. Where people can’t choose for themselves, people do what they can to help them.

“Things are not perfect but we will get there. It might not be in my life time but we will get there.” Edwards’ determination and optimism are inspiring.

The campaigner was made an MBE last year in recognition of his services to the community.

He says he was very proud to get the award, both for himself and for the organisation, but it is not the most important thing: “I didn’t do this to get an MBE. I wanted to make life better for other people.”

When Prince William awarded him the medal, Edwards found himself alongside award recipients including Simon Le Bon, lead vocalist of Duran Duran. Edwards says the singer told him he had heard of MLMC.

Edwards turns to Sophie Bolton, MLMC’s communications officer, who is sitting in with us: “We must chase that up, Sophie!”

Bolton duly takes a note then asks Edwards what he is most proud about. His answer is simple: “Getting the charity to where we are now.”

Beware the big head

At the time of our interview, he was looking forward to a party to celebrate his MBE, laughing as he adds: “But I don’t want to blow my own trumpet too much or my head might expand. I wouldn’t be able to get out of the door.”

I went up to People First in Nottingham and that’s when the idea came. Well, why can’t we do it?

Finally, I ask if I can take a few pictures to go with this interview. Edwards agrees. It is a cold day and he is dressed for winter but, as our interview will be published in April, I suggest the editor would appreciate it if he removed a layer so the photograph looks more seasonal.

Edwards’ answer is unequivocal, direct and forthright – exactly as you would expect from a successful self-advocate: “No. Absolutely not. If they don’t like it, they don’t have to use it.” The coat, quite rightly, stays on.