In medieval times, the term “idiocy” could mean simply an uneducated, ignorant person and, for the small, educated elite of this period, that description applied to most people.

However, it could have a more specific meaning: a person with a more marked deficiency who might struggle to understand the basics of everyday life.

Idiocy, because of its incurable, unchanging nature, was of no interest to doctors, whose trade depended on the ability to cure.

The responsibility for care for the idiot person remained with the family and the community.

Nor was idiocy seen as a religious matter. Being natural – so determined by God – it was not generally seen as a mark of sin.

Overwhelmingly, idiocy was perceived as a practical matter, related to ability to function in society. Those who might be diagnosed as having a moderate learning disability were simply able to get on with it in a society where most people were illiterate and the ability to “get by” was the main prerequisite of daily life.

War work

In 1917, as the First World War raged, Leslie Scott, chairman of the Central Association for the Care of the Mentally Defective, turned his mind to the peace.

“There are,” he wrote, “large numbers of low-grade, even imbecile defectives, now in remunerative work who will assuredly leave their work when there is any displacement of labour, and we are anxious to make plans for their protection.”

The country’s need for manpower, with so many fighting on the front, had changed almost overnight, with the perception of the “mentally deficient” changing from people incapable of work to useful members of the workforce.

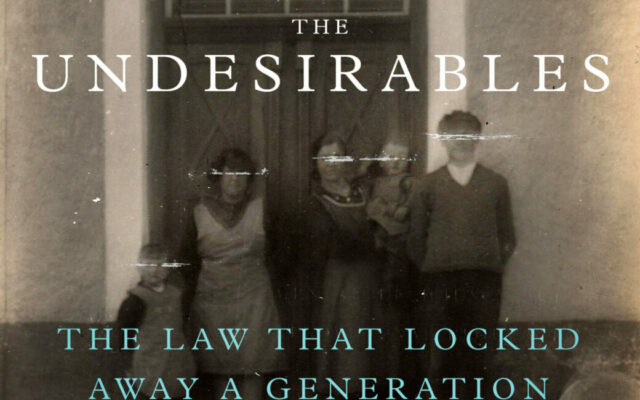

A draconian Mental Deficiency Act had been passed in 1913. This had characterised the “mentally deficient” as incapable, non-productive and a threat to the health of the nation. The legislation sought their eventual eradication through institutionalisation and close surveillance.

The act, however, was put on hold by war. Many thousands of “mentally deficient” people took up valuable and skilled roles from 1914 – some joined the armed forces.

It was a dramatic and rapid transformation from useless to useful – a stunning example of how social attitudes, circumstances and assumptions can construct the meaning of disability at any time.

Creating their own community

The first Camphill school was founded by a group of German and Austrian Jewish refugees from Nazism. Led by Karl König, a Christian convert, they wanted to create a new form of “healing environment” for children with special needs.

They rejected the fashionable idea of the time that some children were ineducable. They wanted to create a community where children with disabilities and (unpaid) staff would live and share their lives to foster mutual help and understanding.

At their first community in Aberdeen in 1940, children with learning disabilities were taught by and lived with mainly Jewish refugee educators. The daily language in the early years was German. Today, there are 22 communities in Britain and many more around the world.

Towards the end of his life, Karl König recalled what brought together this unlikely alliance in their own community, outside mainstream society: “The handicapped children were in a similar position to ours. They were refugees from a society which did not want to accept them as part of their community. We were political, these children social, refugees.”

Photos: Robin Jackson

Photos: Robin Jackson