In Italy, a 1904 law stated that anyone deemed a danger to themselves or others, or whose behaviour might cause a public scandal, should be admitted to an asylum.

It applied to everyone considered “deviant” from social norms, including children and learning disabled people. Patients were referred by families, doctors or the police. They were segregated by sex, had their heads shaved and personal items removed and, effectively, prepared for indefinite incarceration.

“Treatment” was dominated by organic approaches: electro-convulsive therapy (ECT), as both treatment and punishment; lobotomy (psychosurgery); insulin therapy; and hydrotherapy (including baths of freezing water). Restraint was common, with patients tied to their beds overnight or to trees when outside, with frequent use of the straitjacket.

In 1965, health minister Luigi Mariotti described Italy’s psychiatric hospitals as akin to Nazi concentration camps or the lower circles of Dante’s Inferno.

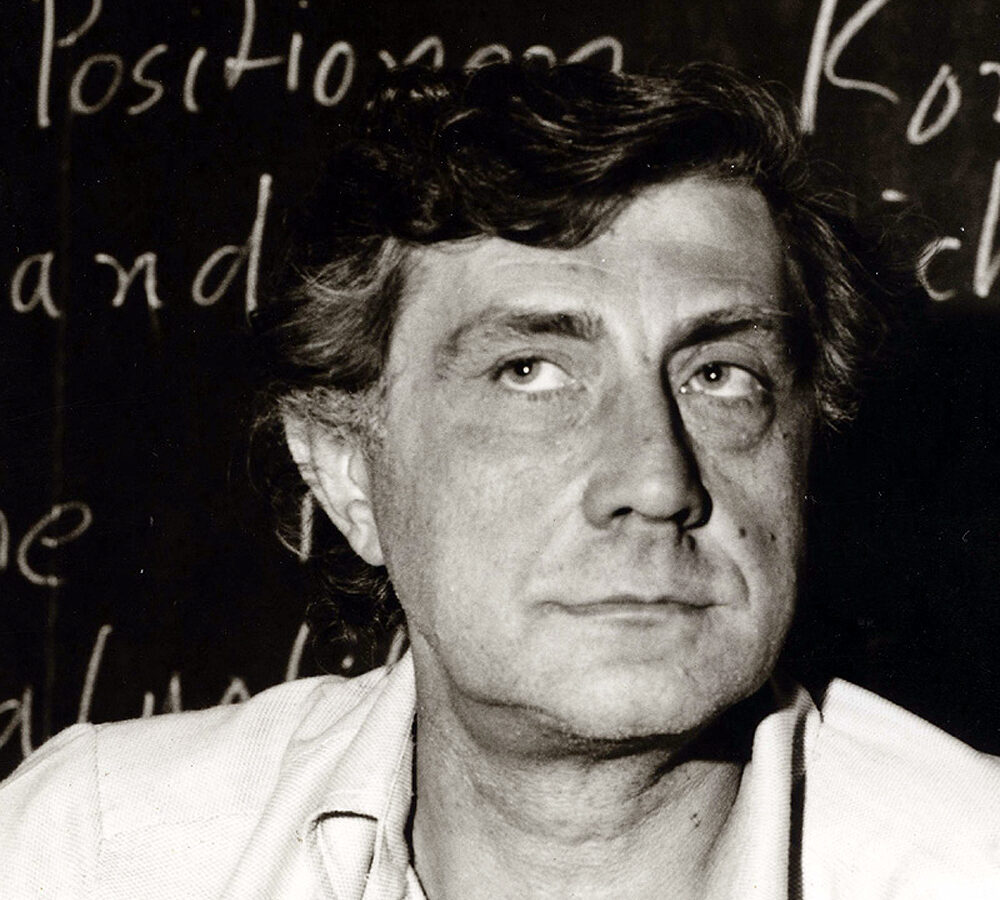

The similarity between asylums and prison camps had also been noticed by psychiatrist Franco Basaglia. In 1944, Basaglia had been interned by the Fascist regime for his political activism. This experience impacted his career, in terms of both his radical ideas and in hampering his job prospects. So, in 1961, he found himself forced to take the only position open to him: director of Gorizia Asylum.

Basaglia was horrified by the insanitary and undignified living conditions and the punitive and inhumane “treatments”. He began to believe that the asylum system was morally bankrupt and “absurd”, a dumping ground for the poor and the deviant, existing to contain people rather than treat them.

Basaglia and his team made changes. Restraints were phased out and ECT massively reduced. Wards were opened up, fences taken down, often with the help of the patients themselves, who were encouraged to go out and find paid work. Patients were invited to attend and participate in hospital meetings, allowed to mix and given access to a hairdresser and bar.

In 1971, Basaglia was made the director of Trieste Asylum where he worked towards its closure. As well as reforms similar to those at Gorizia, co-operatives eased the transition from asylum to work alongside community housing, some of it in the institution itself.

Despite some fierce opposition, particularly from the press and judiciary, Basaglia attracted powerful political allies as well as students, activists and like-minded professionals from across Europe.

They worked with the patients (who became paid volunteers as they were discharged) to transform Trieste into an experimental space, host to exhibitions, plays, conferences and art projects.

Trieste asylum closed in 1979.

He believed the asylum system was morally bankrupt, a dumping ground for the poor and the deviant, existing to contain rather than treat people

In 1978, the Basaglia Law effectively abolished Italy’s asylum system, making it illegal to commit anyone to a psychiatric hospital. It gave provision for co-operatives to be established, aiming to return patients to society and work.

Its implementation was not smooth. It took nearly two decades to close all the asylums, with high-profile cases of ex-patients who went on to kill – partners, parents or themselves.

Families who had had their more problematic members institutionalised for decades struggled to welcome them back into their homes and lives. Many seriously ill people soon ended up in prison, and many learning disabled adults were left unsupported.

Nevertheless, most of the 100,000 former patients were reabsorbed into society. With people feeling moved by the widely circulated media issued by the movement and appalled by institutions that recalled the harsher, more unequal world of the Fascist regime, deinstitutionalisation had widespread support.

Today, there are no asylums in Italy; their grounds are used for museums, health centres and parks.

Further reading

Foot J. Franco Basaglia and the radical psychiatry movement in Italy, 1961-78. Critical and Radical Social Work. 2014;2(2):235-249

Foot J. The Man Who Closed the Asylums. London and New York: Verso; 2015

Foot J. Closing the asylums. Jacobin. 5 November 2018.