Paul Williams describes the remarkable achievements of the young man with learning difficulties who ruled on the throne of Spain for 35 years at the end of the 17th century.

Paul Williams describes the remarkable achievements of the young man with learning difficulties who ruled on the throne of Spain for 35 years at the end of the 17th century.

Overlapping the reign of Charles II of England (1660 to 1685) there was another Charles II on a European throne. Known in Spain as Carlos Segundo, he was king of that country from 1665 to 1700. He was born in 1661 with multiple physical impairments, epilepsy and learning difficulties. When he was only four years old his father, Philip IV, died and as Philip’s only legitimate son Carlos automatically became king.

Descriptions of Charles in history books and on internet sites are overwhelmingly negative, even using words like ‘monstrosity’. Towards the end of his life, when his epilepsy worsened, he was thought by some to be possessed by evil forces and he was sometimes described as ‘El Hechizado’ (‘The Bewitched’).

However, this prejudicial view can be challenged. Charles was a survivor of all his difficulties, he was a popular monarch, and he achieved much during his reign that was highly positive and ensured a strong future for Spain.

Constant companion

Charles’s mother, Queen Mariana, acted as his Regent during his childhood and was his constant companion and adviser until her death in 1696.

In 1679, at the age of 18, he was married to a French princess, Marie Louise of Orléans, a granddaughter of Louis XIII. It was hoped that Charles would produce an heir who would carry on the dynasty of the Habsburgs in Spain, of whom Charles was the last member. Charles did not do this and is usually described as impotent.

He certainly seems to have been infertile but not necessarily impotent, since there is some evidence that he and Marie Louise had a good sexual relationship. Charles was heartbroken when Marie Louise died in 1689, probably of appendicitis.

Again to try to secure an heir for him, Charles’s advisers immediately arranged another marriage, this time to Maria Anna of Neuberg, the daughter of a prominent German prince. This marriage was less happy, but Maria Anna became a strong companion and adviser to Charles until his death.

Charles had limited concentration but took his role very seriously and spent a short time each day with his mother and his advisers expressing a view and coming to decisions. He had little schooling and never learned to read or write but he did learn to write his signature (‘Yo el Rey’ meaning ‘I the King’) in order to sign decrees and documents.

Charles was much loved by his people. When he was ill, crowds would appear outside the royal palaces to wish him well. In 1680 and 1682 two highly visible comets appeared in the sky over Europe (the latter was Halley’s comet). These were thought to be an ill omen for the king and prayers were said for him all over Spain.

Charles lived of course long before the invention of photography but his image, and those of his mother and two wives, and of some events in his life, were recorded in paintings, mainly by the two artists appointed to the Court, Claudio Coello and Juan Carreno de Miranda. Many of these can be viewed on the internet. Charles is portrayed in fine clothes and with the regalia of the highest honours in Spain at that time.

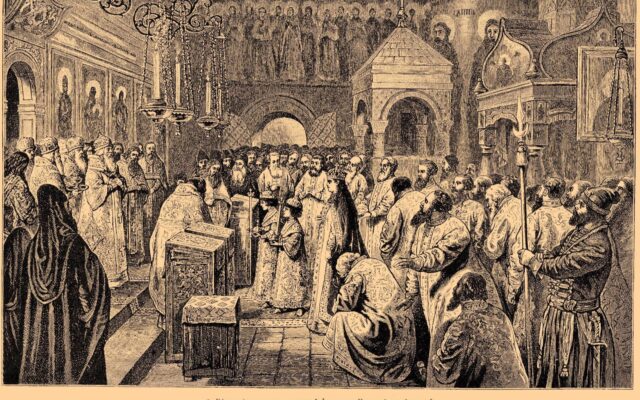

One of the events depicted in these paintings is an ‘auto-da-fe’, a large outdoor religious ceremony held to decide the fate of people accused of offences under the Spanish Inquisition. The one represented was held in 1680 and was planned as the largest and grandest to have been held in Spain. It was presided over by Charles, accompanied by his wife and mother. Belying his supposed lack of concentration, Charles paid rapt attention to the proceedings for the whole day. The ceremony involved 120 prisoners, but only 21 were sentenced to death – probably indicating a merciful approach by Charles. Later in his life he expressed opposition to the Inquisition and just before his death he ordered a critical report to be prepared with a view to its abolition.

Short stature

Charles lived mainly in two royal palaces in Madrid, the Alcazar and the Buen Retiro, where the affairs of state were carried out. However, his favourite palace was the Escorial, situated in the countryside about 30 miles outside Madrid. This was a monastery where Charles found peace and contentment. It also housed, as was common in royal palaces throughout Europe at the time, a number of people perceived as different, including people of short stature and people with learning difficulties. These are often described as ‘clowns’, ‘buffoons’ or ‘jesters’ but they were actually much loved companions of royalty, bringing luck and honesty to the court. Charles’s favourite was Eugenia Vallejo who had what is thought to be Prader-Willi syndrome which caused her to weigh 12 stone at the age of 6. Charles had a portrait of her painted by Carreno de Miranda.

In 1671, when Charles was only 10, a severe fire destroyed much of the Escorial palace and Charles became determined to restore its splendour during his reign. To complete this work in the 1690s, Charles recruited the Italian painter Luca Giordano, famous for his large frescos, to paint historical scenes on the ceilings of the palace, including one which can still be viewed above the main staircase depicting Charles, his mother and his wife.

The period of Charles’s reign was a relatively peaceful one in Spanish history. Spain lost some of its possessions in Holland, Belgium and Portugal but Charles seems to have preferred to accept this rather than engage his country in lengthy and expensive wars.

Spain also had colonial possessions in America, particularly in Florida. There was great opposition between this colony and the neighbouring British colony of South Carolina. In 1693, Charles passed a decree that slaves who escaped from South Carolina to Florida would be given freedom and protection there. It is not known how many slaves this involved but probably hundreds if not thousands of slaves gained a better life because of Charles’s action.

Charles’s epilepsy became worse in the 1690s and, believing he was bewitched, Spanish doctors tried to treat him with superstitious remedies, one of which involved placing dead pigeons on his head. Charles was not happy with this and ordered that advice be sought from Italian doctors who had developed a more scientific approach to medicine. Thus, Charles can be said to have introduced more effective medical knowledge to Spain.

The two separate provinces of Aragon and Castile had been brought together by Charles’s ancestors Ferdinand and Isabella in the 15th century. Conscious that Spain might be split up again because he did not have an heir, Charles decided shortly before his death that the only way to avoid this was to bequeath the throne of Spain to a French prince, Philip of Anjou, and he signed a will to this effect.

Influential

Charles is often severely criticised for this by historians because it led to a violent war, known as the War of the Spanish Succession, which took place between 1701 and 1714 involving an alliance of England, Holland and Austria against France and Spain. Despite this, Charles ensured the unity of Spain which it has enjoyed ever since.

Charles died in 1700 at the age of 39 and is buried alongside other Spanish rulers in a tomb within the Escorial palace. Far from seeing him as a ‘bewitched monstrosity’, we can celebrate the life of this courageous young man with learning difficulties who was an important, beneficent and influential person in European history.

Further reading

John Nada (1962) Carlos the Bewitched. London: Jonathan Cape.

Henry Kamen (1983) Spain in the Later Seventeenth Century. London: Longman.