Robin Jackson tells the extraordinary story of Hermann Gross, a German Expressionist artist who lived amongst a community of children with learning disabilities and was inspired by them to paint on themes of social renewal, interdependence and the meaning of vulnerability.

Quote: For the founders of Camphill and for Gross, the search for new social forms was never an abstract idea — it was an urgent necessity. As the community gave his work new life, so he offered new life to the community.

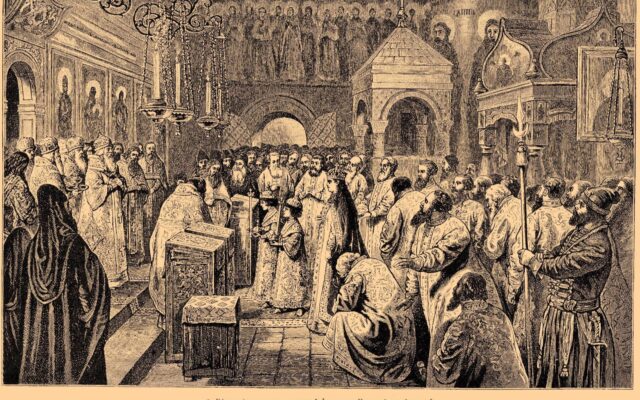

At the beginning of World War II Dr Karl Koenig and a group of refugees from Austria and Germany founded the first Camphill community in Scotland. Koenig had developed a vision of a ‘learning community’ where the traditional boundaries between professional disciplines would be dissolved, the spiritual well-being of those living in the community nurtured and respected, creativity, spontaneity and originality encouraged and where ecological sensitivity and responsibility would be exercised.

Koenig was looking at one possible way to generate social renewal at a time of social disintegration and to send a message of hope at a time of widespread despair. Having experienced some of the horrors of a hate-fuelled Nazi regime, Koenig was determined to create a community in which compassion and tolerance were present, for it was compassion and tolerance that bound communities together. It was Koenig’s belief that co-workers in the communities should live and work together with children and adults with special needs in such a way that new social forms might develop: the co-workers would share every aspect of their lives with the children and work without remuneration.

Inspiration

It was to this distinctive community that Hermann Gross – a German Expressionist artist and former pupil of Picasso – came to live and work. Working in this residential setting became a source of inspiration for him. Both for the founders of Camphill and for Gross, the search for new social forms was never an abstract idea — it was an urgent necessity. As the community gave his work new life, so he offered new life to the community.

It had always been one of the aims of the founders of Camphill to foster social art. Gross began a process whereby people were challenged to look at their surroundings in a new way. This stimulated an interest in what was put on the walls of the houses and meeting rooms and in the gardens. Gross made a significant contribution to the community’s understanding of the purpose and value of art, not simply by making his work available to the community but by ensuring that the art-making process itself was accessible and visible and not some precious and exclusive activity. In essence, he was engaged in the demystification of the process – but not of the product.

Gross’s work is unusual insofar as there are relatively few examples of children as principal subjects in either classical or modern art – apart from the iconic representations of the Christ child – yet children feature strongly in his work. Not only does Gross take children as his main subjects but he goes one step further and encourages the viewer to reflect upon the transient nature of childhood and all the vulnerabilities inherent in it. The challenge for the artist is to be able to convey that message without recourse to the cloyingly sentimental images that characterised much of Victorian illustrations depicting childhood.

Gross does not present a form of sentimental art that leads the viewer away from active engagement with the ambiguities and complexities of the real world. Sentimentality in art makes no demands upon us, requires no struggle, involves only a narrow range of feelings, arouses no thoughts or feelings about the real world: it represents a general failure of imagination. Gross was aware that the kind of social renewal that his Camphill colleagues sought could only be achieved by creating a world that was more responsive to the needs of the child. He was engaged in social art, where the medium is being used to convey an ethical message, not simply about how one should care for and protect children but how societies should treat all vulnerable groups.

Sense of community

When Gross was artist-in-residence in Aberdeen, a significant number of children attending the Camphill School were drawn from some of the most socially deprived districts in Glasgow with which Joan Eardley – a distinguished Scottish artist – would have been familiar. Both Eardley and Gross succeeded in persuading the viewer to treat children as serious subjects by portraying them with compassion and without sentimentality. Eardley’s paintings demonstrate that, notwithstanding personal circumstance, the child possesses an inner resilience that transcends that circumstance, however disadvantageous. She was particularly attracted by the friendliness and community spirit in these districts. In different ways both Eardley and Gross were commenting upon the importance of a sense of community. By the time of Eardley’s death in 1963 many of the old tenement districts had been levelled to the ground and residents transferred to soulless high-rise estates. In the process that strong sense of community that had so appealed to Eardley had gone.

Eardley differed from Gross in that she tended to focus almost exclusively on the child, whereas Gross invariably sets the child in the context of a relationship with one or more adults. Whilst Eardley stressed the independent identity of the child, Gross highlighted the importance of inter¬dependence – an essential feature of life in a Camphill community. The life-sharing aspect of Camphill community life is one of its defining features, as this ensures that the principles of dignity and mutual respect can be meaningfully translated into practice. And it is this mutual relationship that provides the cohesive force that binds together the different elements of a community: it is the mortar without which the communal edifice would collapse.

Reference

Robin Jackson (2008) Hermann Gross: art and soul. Edinburgh: Floris Books.