Helen Atherton and Florian Schwanninger discovered the name of a young woman with learning disabilities born in the UK and murdered at a Nazi killing centre on a memorial plaque. They decided to find out everything they could about Ivy Angerer, and her story can finally be told.

Helen Atherton and Florian Schwanninger discovered the name of a young woman with learning disabilities born in the UK and murdered at a Nazi killing centre on a memorial plaque. They decided to find out everything they could about Ivy Angerer, and her story can finally be told.

Schloss Hartheim, an old castle near Linz in Austria, became an institution for mentally disabled people in 1898. In 1940, it became one of six killing centres established to fulfil the goals of a Nazi euthanasia programme known as Aktion T4.

The programme, with its headquarters in Tiergartenstrasse 4 (T4) in Berlin, targeted and sought to eliminate those whose lives were deemed ‘unworthy of life’. During 1940 and 1941, around 70,000 adults with learning disabilities, mental health problems or other disabilities were murdered in the German Reich by carbon monoxide gassing under the aegis of Aktion T4. From 1941, tens of thousands more died in clinics through deliberate neglect, hunger or harmful drugs.

In total, there were at least 200,000 victims of Nazi euthanasia, 30,000 of them at Schloss Hartheim. Aktion T4 was the precursor to the Holocaust against the Jewish people, in which many of its personnel actively took part.

Little is known about the lives of the victims. Their anonymity reflects the marginalisation of people with disabilities in life and in history. Only recently have their names finally been released, and research into their lives remains in its infancy.

Finding Ivy Angerer

We saw the name Ivy Angerer on a plaque commemorating people murdered at Schloss Hartheim. It was intriguing to see she had been born in Scotland.

Five years ago, we decided to investigate who she was, to give a voice to the ordinary person behind the name and to rebuild Ivy’s life. With help from German, Austrian, Polish and British archivists, our journey has involved online censuses, birth and marriage records, newspapers, International Red Cross archives and records of enemy aliens.

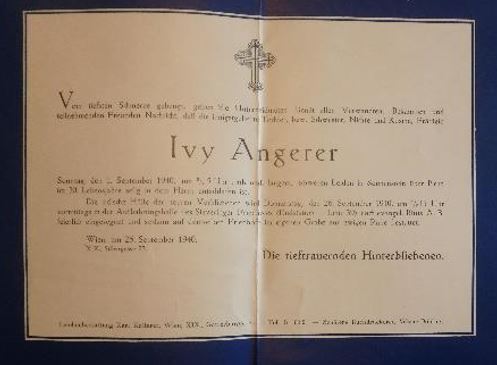

We discovered the existence of a family grave in Vienna, which we visited to find that Ivy was buried there. Through this, we were able to make contact with family members, who then held a family meeting at the grave on All Hallows Eve to discuss whether they would allow Ivy’s story to be told publicly. They agreed it should be.

Earlier this year, we met family members at a Vienna cafe, where they handed us an extensive family archive relating to Ivy, including historical documents and photographs.

The family also granted permission for Ivy’s name to be made public – an important part of her being able to have ownership of her story.

Ivy’s story

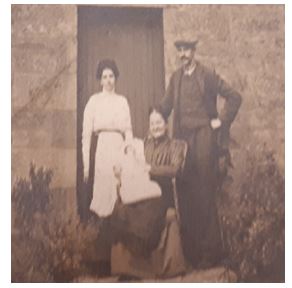

Ivy Berta Meta Angerer was born in 1911 in Broughty Ferry, near Dundee in Scotland. Her mother, Maria Neuman, was from Silesia in Prussia, and her father, Josef, from Vienna. Josef worked as a confectioner and was described as a hardworking and conscientious employee. It is unclear why they came to Scotland but migration was common at this time as people escaped poverty at home.

Ivy had a learning disability. Her medical records indicate that she had a ‘congenital and early acquired state of imbecility without detectable cause’.

Regardless of her diagnosis, early photos clearly indicate that she was a dearly loved child. However, the family’s happiness was to be short lived.

During the spy fever of the First World War arising from fear of a German invasion, Ivy’s father Josef, along with many other German and Austro-Hungarian men living in Britain, was arrested and held in enemy alien camps for the rest of the war. There is no evidence that he was any sort of spy.

It is assumed that Marie and Ivy were repatriated to Marie’s hometown of Halbau in Silesia. Marie died in 1916. Motherless and with her father absent, Ivy was probably cared for by family members.

A picture of Marie’s grave sent to Josef while in the camps shows he was aware she had died. Having been forcibly separated from his daughter, he had now lost his wife. In 1919, Josef was repatriated. He was reunited with Ivy and returned to work as a confectioner in Vienna, marrying a fellow worker in 1923.

Ivy attended school and her reports indicate that she was hardworking and good at singing but struggled with the more academic subjects.

In 1931, aged 20, she was admitted to the Am Steinhof psychiatric hospital in Vienna, the largest institution in continental Europe with 3,000 beds.

Between 1940 and 1945, it was to bear witness to the murder of more than 700 children in the first phase of the Nazi euthanasia programme.

Ivy’s medical records state that she had been admitted (under guardianship) because of mental illness. She was categorised as a ‘high-grade’ imbecile. The annual medical review indicated that she was generally healthy, quietly independent and worked in the laundry. However, she was said to be prone to episodes of confusion. Little else is known from the brief annual medical reports.

Ordinarily, Ivy would probably have remained at Steinhof; however, these were not ordinary times. In 1938, a significant event was to change the course of this young woman’s life.

Nazism comes to Austria

In March 1938, German troops invaded Austria. Hitler announced the Anschluss (connection) of Austria to the German Reich. In Vienna, he was received enthusiastically by many.

Tens of thousands of political opponents and Jews were arrested or abused. German laws on eugenics and racial hygiene, which decreed isolation and sterilisation for ‘carriers of inferior genetic material’, became valid in Austria.

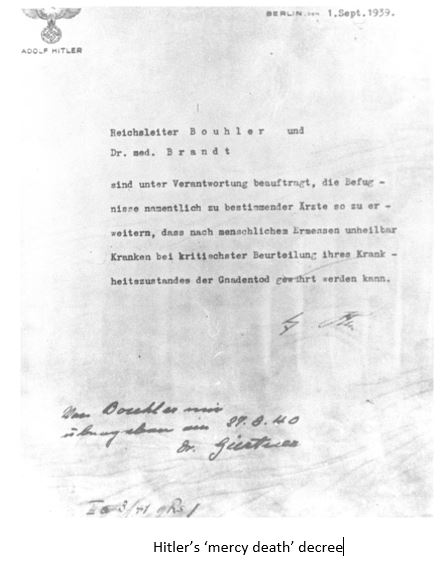

In October 1939, under the cover of war, Hitler signed the so-called ‘mercy death decree’, which provided the legal basis for a programme of extermination of people labelled ‘useless eaters’.

In late 1939, several thousand psychiatric patients and disabled people were shot in occupied Poland, and the first experiments in murdering patients with gas were carried out. At the same time the so-called ‘Kindereuthanasie’ (child killings) began. Disabled infants and toddlers were reported by midwives and doctors and sent to ‘children’s departments’, where they were drugged or died through neglect.

A programme of murder by gassing at six killing centres was planned. Aktion T4 began in early 1940. It involved the registration of all patients with disabilities, whose fate was decided by doctors who examined their forms in Berlin or commissions of doctors sent to institutions to select patients for extermination. It can be assumed that Ivy Angerer was examined at Steinhof by such a commission and deemed to have a ‘life unworthy of life’.

At the centres, the method of killing was the same. Patients were told they would be moved to a new facility. To avoid detection, families were never given correct information about where their relatives had been taken. Ivy’s family was told she had been taken to a town in Saxony in Germany but her destination was in fact Hartheim, some 180km from her hometown. Nurses accompanied the transports to the killing centres on special grey buses.

Up to 80 people worked in Schloss Hartheim, including psychiatrists, nurses, administrators, chefs, janitors and crematorium workers.

When the buses arrived, the victims were taken inside. They were stripped and received by a doctor and nurses in white coats, who told them they were in a new clinic and would now be showered. The gas chamber was disguised as a shower room.

After death, the bodies were taken to the crematorium. Their ashes were poured into the Danube or sometimes sent in urns to families. Families received death certificates with fabricated causes of death. Ivy’s cause of death in 1940 at the age of 29 was registered as ‘acute liver atrophy’. Many families suspected their relatives had not died a natural death.

Knowledge of the murders spread throughout the German Reich. There were rumours and unrest, including a protest by family members at Am Steinhof.

Finally, in August 1941, Hitler stopped Aktion T4. He feared the deterioration in the mood of the population. However, the murders continued, with tens of thousands dying in hospitals through deliberate neglect or direct murder by doctors and nurses.

Ivy’s legacy

Ivy’s story is an important contribution to the history of Aktion T4; it also encourages critical questioning of attitudes to the most vulnerable today, in particular people with learning disabilities and the true extent to which they are accepted as valued citizens.

While one would hope that wholesale killing is a thing of the past, subtle and increasingly socially accepted practices that can lead to the same outcome persist. Think, for example, of antenatal screening for Down syndrome and the poor-quality healthcare that contributes to men with learning disabilities dying on average 13 years and women with learning disabilities 20 years earlier than average. Think of the controversies over ‘do not attempt resuscitatation’ notices for patients with learning disabilities in NHS hospitals. Nazi euthanasia demonstrates in a shocking way what happens when the value of a human life is measured in purely economic terms.

Ivy’s story carries a powerful message about the necessity of promoting people’s humanity and their belonging in communities and society. We must hear the message, and we must remember Ivy.

Helen Atherton is a lecturer in nursing at University of Leeds; Florian Schwanninger is director of the Schloss Hartheim Learning and Memorial Centre in Austria