Michael Baron, himself the father of an autistic son, reviews this novel about the dramas of a family struggling to cope with a profoundly disabled boy.

Michael Baron, himself the father of an autistic son, reviews this novel about the dramas of a family struggling to cope with a profoundly disabled boy.

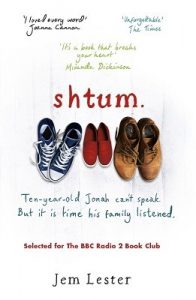

Shtum, the Yiddish word for silence, infers and contradicts the very articulate North London setting for this riveting, often witty, colloquial and sad, debut novel. Though there is a happy ending, of a sort, since autism is for life, for me it was a compulsive read as the agonies of the Jewell family develop.

I have been there and wondered why, as a parent with literary ambitions, I had not written it 50 years ago. But it could not have been written then. Far too many children were diagnosed, in the world’s ignorance, as subnormal, ineducable and confined in large hospitals. Yet, in 2011 there was the scandal of Winterborne View and today the disgraceful long stays in short term assessment and treatment units.

Challenge

My ASD son is now 60. I am like the narrator Jem Lester. I am his fictional protagonist, his anti-hero, if you like, the 37- year old Ben Jewell. Jonah, aged 10, is the child of Ben and Emma. Together they face the existential dilemma of all parents who live with autism. How, why, where, and who will act up to the challenge? This is not a book that makes its points in the exceptional quirky, headline-grabbing way that made Mark Haddon’s The Curious Incident of the Dog In the Night-time a best seller, or as in Dustin Hoffman’s highly realistic performance in the film Rain Man. Both were and continue to be effective global advertisements for autism. It’s real and it happens to us. And it is worse than the lives portrayed in the 2016 TV drama The A-Word.

This novel could not have been published in the 1960s when children who were ‘mentally handicapped’ were in a sense imprisoned, their behaviours as violent and unpredictable as Jonah’s, in institutions of variable quality. Not so any more but the challenge remains.

When the novel opens, Ben is working in the media but is sacked for his drinking habits. Then he becomes the manager of the kitchen equipment hire business founded by his father Georg, a Holocaust survivor. Originally from Hungary. Georg Jewell is silent about his early life story, portraying a different sort of violence only revealed in the last chapter of the book.

But silence is not an option for the parents of this profoundly learning disabled boy, self–harming, doubly incontinent and so still in nappies. The public only glimpses the behaviour that wrecks marriages when there are newspaper headlines or appeals on websites for petitions to be signed about atrocious care.

Where Ben meditates on his lot, drowns his sorrow in drink, I meditate with him. It could have been me had it not been for the great teachers, schools, care homes, and the love and friendship of other parents. As I read Shtum, this story spoke to me and to thousands of young parents. We knew we did not have on our over-worked hands, our companion to sleepless nights, that computing genius who was to hack into the Kremlin’s security network and save the world. If this review is special pleading, then I plead guilty but I am seriously proud to find a tale which mirrors exactly the circumstances of having in the family an autistic profoundly disturbed child.

Rather than ‘autistic’ I prefer a definition of learning disabled with communication disorders but that is a grouse about today’s simplistic use of one–word labels for complex conditions, and the ever expanding statistics of incidence. How Ben manages himself, his business, a failing marriage, a wise father dying of cancer, the search for the best school, finding money for lawyers for the necessary SEN tribunal is not an unfamiliar story but one that had to be told.

Battle

How to do the best is the parents’ mantra, better expressed by Ben in the conference with the barrister hired for the tribunal where parents battle with cash-strapped local authorities for specialist educational provision as “I’m here to provide the best possible future for my son and so my wife and I can share a home again”. Yes, and it is the main strand in the novel. The parents separate so that Ben can pose, as he in fact becomes, a single parent coping with a grossly difficult child with the help of father and friends. That best future is not the day school preferred by the borough but the residential school which father and son, each in their own way, know is right.

How Ben triumphs is the not-quite happy ending. There is a coda. His father’s story is just that, with more than a hint of a genetic connection to the past.

At the end the imaginative reproduction of a postcard, “I love you, Jonah… Daddy XXXX” goes to the heart of what this book is about – love and survival. Read it.

Shtum by Jem Lester is published by Orion, £12.99.