My PhD project is called Not for Them or on Them: Exploring advocacy Outcomes With People With Learning Difficulties and was carried out with a group of people with learning disabilities who use advocacy.

The research looked at the outcomes and impact of advocacy from the point of view of those who use these services. Part of its originality lies in the fact it involved working with the people who use advocacy services instead of other stakeholders as is common in research practice.

Dorothy Atkinson (1999) described advocacy as “speaking up” for yourself or others but I believe it is rarely that simple. Advocacy is based on the fundamental principle that all people are citizens with the same rights and responsibilities and that there is a need to combat the exclusion and marginalisation experienced by members of our society through promoting access to human as well as legal rights (Gray and Jackson, 2002).

Advocacy has been largely overlooked by mainstream research, particularly from the point of view of those who use these service (Ridley et al, 2018).

The research study was carried out with self-advocates and advocacy partners with learning difficulties (the preferred term of the group, as opposed to learning disabilities), who had varied levels of advocacy experience.

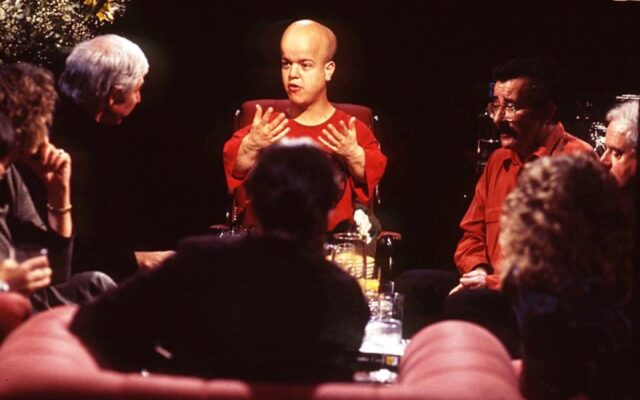

The self-advocates were part of a well-established group that already had a number of high-level achievements at local, regional and national level. For instance, the self-advocacy group had achieved improvements in regional transport infrastructure as well as a number of successful placements to independent living for group members.

‘Going the right way: the self-advocates had achieved improvements in local transport’

To capture the essence of advocacy

Finding homes for supported living can be difficult. Lisa Brown is bringing property investors and care providers together to design and create accommodation to meet various needs.

The idea behind the research study was born and nurtured within the self-advocacy group meetings. Group members felt that exploring and capturing the essence of advocacy partnerships while learning in the process would be of great benefit.

The self-advocates were involved at all stages of the research process.

Training workshops were provided following the “challenging inequality” model developed by Warren and Boxall (2009). This recognises that groups of researchers with different levels of experience need support and training to carry out high-quality research.

The study adopted the principles of different methodologies rather than taking a purist approach. In particular, it used those of participatory research, an approach that facilitates the active involvement and contribution of those taking part (Northway et al, 2014).

Focus groups and narrative interviews with 13 people explored the outcomes and impact of advocacy.

The findings suggest that advocacy produces mainly two types of outcomes. There are end-point outcomes, which involve reaching (fully, partly or not at all) a practical target, such as a house move, agreed at the start. There are also process outcomes, such as learning and/or positive feelings, which are associated with the advocacy partnership’s journey.

The participants reported that both types of outcome were valued. They highlighted that process outcomes were important and valued even if the desired end-point outcome was not reached.

People using the service valued a number of different advocacy outcomes, with nine main themes identified. The main ones were “felt listened to”, “on my side” and “speak up”.

“Advocacy qualities” such as being independent, and “empowerment” to self-advocate were also identified. Other themes were “work together”, “feelings”, “impact for the person”, “learning”, “satisfaction” and “short- and long-term end-point outcomes”.

The project demonstrated that people with learning disabilities who have no research experience can be actively involved as co-producers and participants in academic research.

The study highlighted the great value as well as the need for and importance of involving those with a wealth of lived experiences in research and other exploration. Active involvement of such people promotes inclusion and can aid a greater in-depth understanding of a topic.

The study concluded with developing the advocacy partnership model, which described the advocacy partnership process or journey and looked at the utility of advocacy work. It argued that advocacy strives to empower people to speak up and self-advocate. However, the best outcomes from advocacy will be realised only when people self-advocate and their views and wishes are listened to and acted upon.

It asserted that, in our current times which are often hostile for people with disabilities, advocacy has an important role to play as an ally, continuing the struggle for a more equal, fair, just, inclusive and equitable society alongside advocacy partners and self-advocates.

Manos Gratsias is a PhD student at Northumbria University. His PhD project is nearing completion

Email: emmanouil.gratsias@northumbria.ac.uk

Twitter: @ManosGratsias

References

Atkinson D (1999) Advocacy: a Review. Brighton: Pavilion Publishing for the Joseph Rowntree Foundation

Gray B, Jackson R (2002) Introduction to advocacy and learning disability. In: Gray B, Jackson R (eds). Advocacy and Learning Disability. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers

Northway R, Howarth J, Evans L (2014) Participatory research, people with intellectual disabilities and ethical approval: making reasonable adjustments to enable participation. Journal of Clinical Nursing; 24(3-4):573-581

Ridley J, Newbigging K, Street K (2018) Mental health advocacy outcomes from service user perspectives. Mental Health Review Journal; 23(4):280-292

Warren L, Boxall K (2009) Service users in and out of the academy: collusion in exclusion? Social Work Education. 28(3):281-297