If we respond carefully to the phenomenon of learning disabilities, we can, I think, understand more about our lives and the world in which we live. Indeed, I suggest that people with learning disabilities provide us with powerful resources of hope.

These are evident in four interrelated areas.

The first is that they can help us rethink the status we grant to intelligence as the most desirable of all human qualities.

Instead, I suggest, we should ask whether clever people are in themselves an absolute good – whether the “brightest” are necessarily the “best” – and ensure that we subject intelligence

to a radically different use, above all to improve the quality of life of all, regardless of cognitive abilities.

Being clever isn’t everything

This has challenged me in the deepest part of my being, but I understand now that it was intelligence that ushered in the awful lie of eugenics and which, in a less terrible way, was used to justify the disproportionate rewards offered to those with supposed intellectual gifts.

I’ve learnt that “stupidity” isn’t the worst thing that can afflict a person, and that when we hear others being dismissed as “idiots”, “morons” and the rest, we should insist that people like my son Joey don’t do any harm to anyone. In other words, being clever isn’t everything.

The second challenge is to our emphasis on productivity as the prime indicator of human value.

Many of us are brought up to believe that there is nothing more important than what we achieve at school, at work, in the public sphere. Politicians readily criticise people who don’t want to work – as “workshy”, “shirkers” and so on – and the media teaches us to resent those who “fail to contribute their fair share”.

One of the things that people with learning disabilities demonstrate, however, is that some things are more important than productivity, and that the moment we judge people by what they achieve, what they make, what they do, we diminish those who find such things hard.

The third challenge lies in the priority we afford to spoken language. It has often been argued that the capacity for speech goes to the heart of what it is to be human.

At the age of 30, however, Joey has no spoken language and very limited literacy, yet manages to express his wishes, fears and desires in all sorts of other ways. He’s certainly a human.

And, as long as we assume that communication simply means speech, we will fail to understand not just people like him who are non-verbal but also the many other means we all use to communicate.

The last way that people with learning disabilities challenge our thinking is in the indefinable area of human happiness.

Friends sometimes ask whether Joey is happy and, while it’s difficult to know for certain, my instinct is that he is certainly better at being happy than the rest of his family or, indeed, most non-disabled people I know.

The moment we judge people by what they achieve, what they make, what they do, we diminish those who find such things hard

We can easily patronise people like my Joey for their ability to be made happy by the simplest of things but perhaps it’s wiser to be jealous.

And in a time when psychotherapists identify a new kind of despair stoked by a superabundance of material goods, Joey’s profound pleasure in willow trees, bunting, flowing water, long hair and the oldest of old jokes should make us pause. Do we know how to be happy and, if not, what can he teach us?

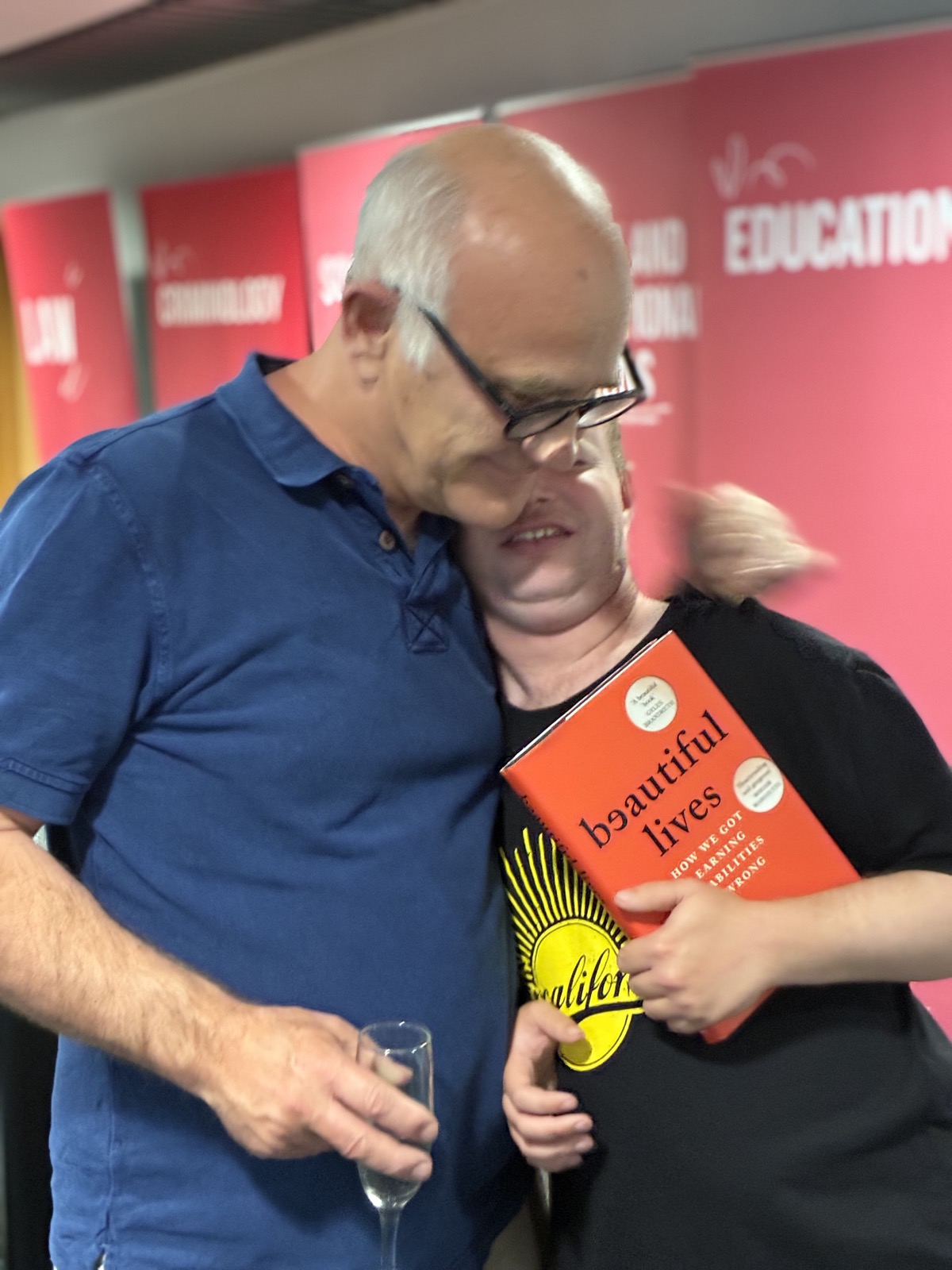

This is an edited extract from Beautiful Lives