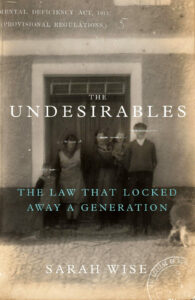

Award-winning Victorian scholar Sarah Wise’s book on the 1913 Mental Deficiency Act concerns individuals detained for social or moral reasons under the moral imbecile category, introduced in this legislation.

Moral imbecile seems to be a category based on dubious claims about someone’s behaviour.

The book has five parts and several appendices, one on how the act worked.

It includes a whole cast of characters. For example, Winston Churchill, home secretary at the time of the act, was a keen supporter of sterilisation. Rather than admission to an institution, he suggested “a simple surgical operation so the inferior could move freely in the world without causing much inconvenience to others”. Unlike many countries, the UK rejected sterilisation.

Among the chapters I enjoyed most was one on the National Campaign for Civil Liberties (now Liberty), which called the 1913 law “the gravest scandal of the 20th century”. Reading about its role in the campaign against it was moving and inspiring.

At the centre of Wise’s account are the patients’ experiences. These include the oral histories of David Barron and Mabel Cooper who, like many, were institutionalised for dubious reasons.

The real sadness is there are still many case histories from which we could learn. Cooper noted how lucky she was to find her hospital records as her NHS trust had destroyed the majority of these.

As Wise notes: “I have only been to scrabble together a few of these case histories. The rest is silence.”

I hope that her excellent guide will develop more curiosity into this act and its consequences; for me, the main thing is to develop more curiosity into people’s lives and their history today.